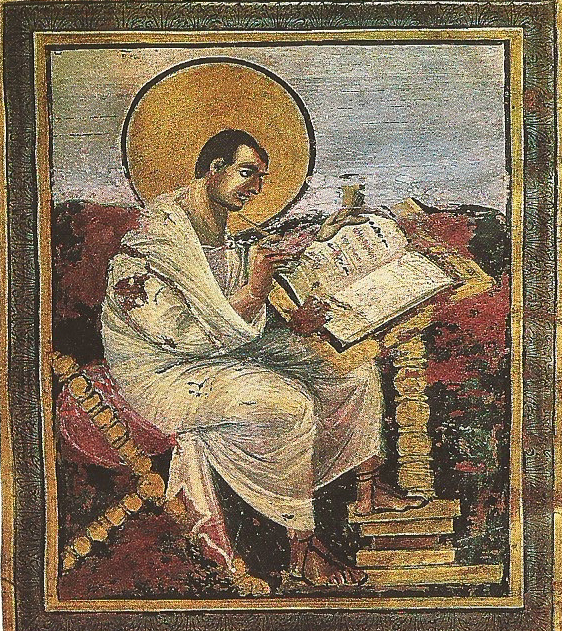

Below, part of Gospel Fictions’ third chapter, “Nativity legends” by Randel Helms (ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages):

Two of the four canonical Gospels—Matthew and Luke—give accounts of the conception and birth of Jesus. John tells us only of the Incarnation—that the Logos “became flesh”—while Mark says nothing at all about Jesus until his baptism as a man of perhaps thirty. Either Mark and John know nothing about Jesus’ background and birth, or they regard them as unremarkable.

Certainly Mark, the earliest Gospel, knows nothing of the Annunciation or the Virgin Birth. It is clear from 3:20-21 that in Mark’s view the conception of Jesus was accompanied by no angelic announcement to Mary that her son was to be (in Luke’s words) “Son of the Most High” and possessor of the “throne of David” (Luke 1:32 NEB [New English Bible]).

According to Mark, after Jesus had openly declared himself Son of Man (a heavenly being, according to Daniel 7:13), his family on hearing of this “set out to take charge of him. ‘He is out of his mind,’ they said.” Surely Jesus’ mother and brothers (so identified in Mark 3:31) would not have regarded Jesus’ acts as signs of insanity if Mark’s Mary, like Luke’s, had been told by the angel Gabriel that her son would be the Messiah.

But Mark’s ignorance of Jesus’ conception, birth, and background was no hindrance to the first-century imagination. Many first-century Jewish Christians did feel a need for a Davidic messiah, and at least two separate groups responded by producing Davidic genealogies for Jesus, both to a considerable extent imaginary and each largely inconsistent with the other. One of each was latter appropriated by Matthew and Luke and repeated, with minor but necessary changes, in their Gospels. Each genealogy uses Old Testament as its source of names until it stops supplying them or until the supposed messianic line diverges from the biblical. After that point the Christian imaginations supplied two different lists of ancestors of Jesus.

Why, to show that Jesus is “the son of David,” trace the ancestry of a man who is not his father? The obvious answer is that the list of names was constructed not by the author of Matthew but by earlier Jewish Christians who believed in all sincerity that Jesus had a human father. Such Jewish Christians were perhaps the forbears of the group known in the second century as the Ebionites.

The two genealogies in fact diverge after David (c. 1000 B.C.) and do not again converge until Joseph. It is obvious that another Christian group, separate from the one supplying Mathew’s list but feeling an equal need for a messiah descended from David, complied its own genealogy, as imaginary as Mathew’s in its last third. And like Mathew’s genealogy, it traces the Davidic ancestry of the man who, Luke insists, is not Jesus’ father anyway, and thus is rendered pointless.

Moreover, according to Luke’s genealogy (3:23-31) there are forty-one generations between David and Jesus; whereas according to Mathew’s, there are but twenty seven. Part of the difference stems from Mathew’s remarkably careless treatment of his appropriated list of names.

Thus we have a fascinating picture of four separate Christian communities in the first century. Two of them, Jewish-Christian, were determined to have a messiah with Davidic ancestry and constructed genealogies to prove it, never dreaming that Jesus could be thought of as having no human father.

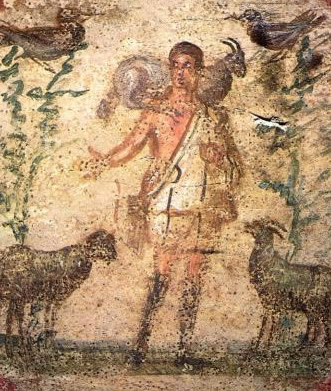

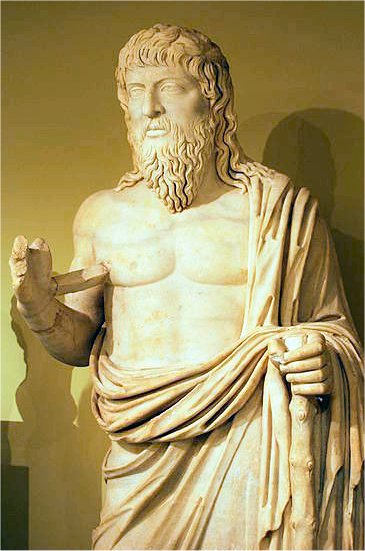

But gentile Christians in the first century, who came into the new religion directly from paganism and were already infected with myths about licentious deities, had a much different understanding of what divine paternity meant. Plutarch speaks for the entire pagan world when he writes, in Convivial Disputations, “The fact of the intercourse of a male with mortal women is conceded by all,” though he admits that such relations might be spiritual, not carnal. Such mythology came with pagans converted to Christianity, and by the middle of the first century, Joseph’s paternity of Jesus was being replaced by God’s all over the gentile world.

“The virgin will conceive and bear a son, and he shall be called Emmanuel,” a name which means “God is with us.” (Matthew 1:20-23)

The Septuagint, from which Matthew quotes, uses, at Isaiah 7:14, parthenos (physical virgin) for the Hebrew almah (young woman) as well as the future tense, “will conceive,” though Hebrew has no future tense as such. Modern English translations are probably more accurate in reading (as does the New English Bible), “A young woman is with child.” We can scarcely blame the author of Matthew for being misguided by his translation (though Jews frequently ridiculed early Christians for their dependence on the often-inaccurate Septuagint rather than the Hebrew). We can, however, fault him for reading Isaiah 7:14 quite without reference to its context—an interpretative method used by many in his time and ours, but a foolish one nonetheless. Any sensible reading of Isaiah, chapter seven, reveals its concern with the Syrio-Israelite crisis of 734 B.C. (the history of which appears in I Kings 16:1-20).

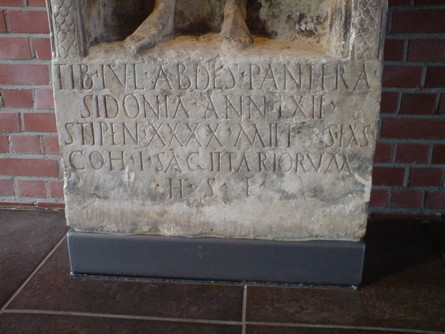

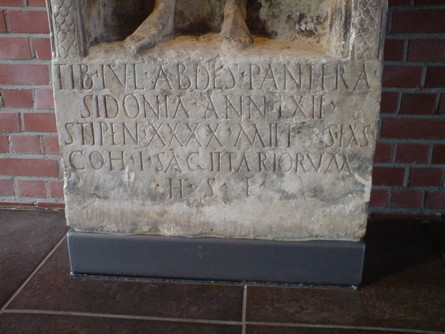

(Jesus’ real father? According to a malicious, early Jewish story, Jesus was the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier called Pantera. The name is so unusual that it was thought to be an invention until this first-century tombstone came to light in 1859; for the Latin inscription see below.)

(Jesus’ real father? According to a malicious, early Jewish story, Jesus was the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier called Pantera. The name is so unusual that it was thought to be an invention until this first-century tombstone came to light in 1859; for the Latin inscription see below.)

It is clear, however, that though the mistranslated and misunderstood passage in Isaiah was Matthew’s biblical justification for the Virgin Birth, it was not the source of the belief (indeed Luke presents the Virgin Birth without reference to Isaiah). The doctrine originated in the widespread pagan belief in the divine conception upon various virgins of a number of mythic heroes and famous persons in the ancient world, such as Plato, Alexander, Perseus, Asclepius and the Dioscuri.

Matthew writes that Joseph, having been informed in his dream, “had no intercourse with her until her son was born” (Matt. 1:25). Luke gives us a different myth about the conception of Jesus, in which the Annunciation that the messiah is to be fathered by God, not Joseph, is made to Mary rather than to her betrothed. Embarrassed by the story’s clear implicit denial of the Virgin Birth notion, Luke or a later Christian inserted Mary’s odd question [“How can this be, since I know not a man?”], but the clumsy interpolation makes hash of Jesus’ royal ancestry.

(The inscription reads: “Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera of Sidon, aged 62, a soldier of 40 years’ service, of the 1st cohort of archers, lies here”; only “Abdes” is a Semitic name.)

(The inscription reads: “Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera of Sidon, aged 62, a soldier of 40 years’ service, of the 1st cohort of archers, lies here”; only “Abdes” is a Semitic name.)

In due course, Jesus was born, growing up in Nazareth of Galilee, a nationality different from the Judean inhabitants of Jerusalem and its near neighbor, Bethlehem. After Jesus’ death, those of his followers interested in finding proof of his messiahnship in the Old Testament worked a Christian reinterpretation of Micah 5:2 concerning the importance of Bethlehem as the birthplace of David and his dynasty:

You, Bethlehem in Ephrathah, small as you are to be among Judah’s clans, out of you shall come forth a governor for Israel, one whose roots are far back in the past, in days gone by.

That is, the one who restores the dynasty will have the same roots, be of the same ancestry, as David of Bethlehem. Prophesying, it would appear, during the Babylonian exile, Micah (or actually a sixth-century B.C. interpolator whose words were included in the book of the eight-century B.C. prophet) hoped for the restoration of the Judaean monarchy destroyed in 586 B.C.

But since some first-century Christians did read Micah 5:2 as a prediction of the birthplace of Jesus, it became necessary to explain why he grew up in Nazareth, in another country, rather than Bethlehem. At least two different and mutually exclusive narratives explaining this were produced: one appears in Matthew, the other in Luke.

Matthew has it that Mary and Joseph lived in Bethlehem when Jesus was born, and continued there for about two years, fleeing then to Egypt. They returned to Palestine only after Herod’s death. For fear of Herod’s son, they did not resettle in Bethlehem. But moved rather to another country, Galilee, finding a new home in Nazareth.

Luke, on the other hand, writes that Mary and apparently Joseph lived in Nazareth, traveling to Bethlehem just before Jesus’ birth to register for a tax census. They left Bethlehem forty days later to visit the temple in Jerusalem for the required ritual of the first-born, returning then to their hometown of Nazareth.

Examination of these two irreconcilable accounts will give us a good picture of the creative imaginations of Luke, Matthew, and their Christian sources.

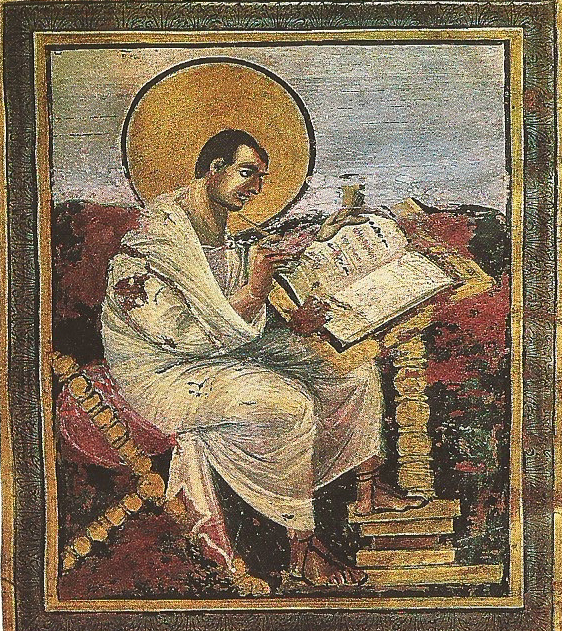

In most of Matthew’s Gospel, the major source of information about Jesus is the Gospel of Mark (all but fifty-five of Mark’s verses appear in Matthew, either word-for-word or with deliberate changes). But Mark says nothing about Jesus’ birth. When one favorite source fails him, Matthew inventively turns to another—this time to the Old Testament, read with a particular interpretative slant, and to oral tradition about Jesus, combining the two in a noticeably uneasy way.

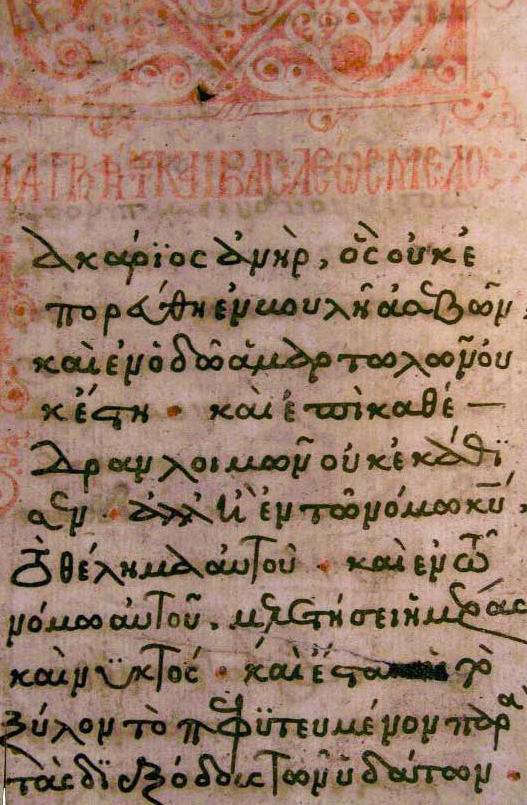

We must remember that for the Christian generation that produced our Gospels, the Bible consisted only of what Christians now called the Old Testament, and a particular version thereof, the Greek Septuagint. But before they wrote the New Testament, Christians created another entirely new book, the Old Testament, turning the Septuagint into a book about Jesus by remarkably audacious and creative interpretation. Meanings it had held for generations of Jews, its historical and poetic content especially, ceased to exist; it became not a book about the past but about its own future.

Of course, other groups such as the Qumran sect also read the Bible oracularly, but Christians specialized this technique, finding oracles about Jesus of Nazareth. If a passage in the Septuagint could be read as a prediction of an event in the life of Jesus, then the event must have happened. Thus, if Micah were understood to mean that the Messiah was to be born in Bethlehem, then Jesus must have been born there, no matter what his real hometown. But as it happens, the Bethlehem birth story, dependent upon the Christian interpretation of Micah, and the magi-and-star legend, dependent upon Hellenistic and Jewish oral tradition, fit together very uneasily. The story of the magi (“astrologers” is a more meaningful translation) says that “the star which they had seen at its rising went ahead of them until it stopped above the place where the child lay” (Matt 2:9).

In all the stories, the astrologers point to a special star, symbol of the arrival of the new force (Israel, Abraham, Jesus). Says Balaam: “A star shall rise [anatelei astron] out of Jacob, a man shall spring out of Israel, and shall crush the princes of Moab” (Num. 24:17 LXX). The astrologers in Matthew likewise point to a star: “We observed the rising of his star” (Matt. 2.2).

Now the source of the story of the king (Nimrod, Herod) who wants to kill the infant leader of Israel (Abraham, Jesus) shifts to the account of Moses in Exodus, the classic biblical legend of the wicked king (Pharaoh) who wants to slay the new leader of Israel (Moses). Indeed, the story of Moses in the Septuagint provided Matthew with a direct verbal source for his story of the flight into Egypt. As Pharaoh wants to kill Moses, who then flees the country, so Herod wants to kill Jesus, who is then carried away by his parents. After a period of hiding for the hero in both stories, the wicked king dies:

And the Lord said unto Moses in Midian, “Go, depart into Egypt, for all that sought thy life are dead” (tethnekasi gar pantes hoi zetountes sou ten psychen—Ex: 4:19 LXX).

When Herod died, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, “Rise, take the child and his mother, and go to the land of Israel for those who sought the child’s life are dead” (tethnekasin gar hoi zetountes ten psychen tou paidiou—Matt 2:20).

Of course, Moses flies from Egypt to Midian, while the Holy Family flees to Egypt through Midian.

* * *

“This was to fulfill the words spoken through the prophets: ‘He shall be called a Nazarene’” (Matt. 2:23). There is, however, no such passage in all the Old Testament. Matthew had apparently vaguely heard that such a verse was in the “prophets,” and since he really needed to get the Holy Family from the supposed birthplace to the known hometown, he reported the fulfillment but left the biblical reference unspecified.

Like Matthew, Luke faced the same problem of reconciling known Nazarene upbringing with supposed Bethlehem birth. His solution, however, was entirely different, and even less convincing. Whereas Matthew has the Holy Family living in Bethlehem at the time of the birth and traveling to Nazareth, Luke has them living in Nazareth and traveling to Bethlehem in the very last stages of Mary’s pregnancy. Though Luke 1:5 dates the birth of Jesus in the “days of Herod, king of Judaea,” who died in 4 B.C., he wants the journey from Galilee to Bethlehem to have occurred in response to a census called when “Quirinius was governor of Syria.”

As historians know, the one and only census conducted while Quirinius was legate in Syria affected only Judaea, not Galilee, and took place in A.D. 6-7, a good ten years after the death of Herod the Great. In his anxiety to relate the Galilean upbringing with the supposed Bethlehem birth, Luke confused his facts. Indeed, Luke’s anxiety has involved him in some real absurdities, like the needless ninety-mile journey of a woman in her last days of pregnancy—for it was the Davidic Joseph who supposedly had to be registered in the ancestral village, not the Levitical Mary.

Worse yet, Luke has been forced to contrive a universal dislocation for a simple tax registration. Who could imagine the efficient Romans requiring millions in the empire to journey scores of hundreds of miles to the villages of millennium-old ancestors merely to sign a tax form!

Needless to say, no such event ever happened in the history of the Roman Empire.