Chapter 5

Anglo-American power and German impotence

The main reason why Hitler withdrew from party management was his plan to write a ‘large book’, which he stated clearly in the declaration announcing his decision. This project began as a quasi-legal defence of his actions for the court. It soon developed into the idea of producing, as Hitler told Siegfried Wagner in early May 1924, a ‘comprehensive settlement of accounts with those gentlemen who cheered on 9 November’, in other words Kahr, Lossow and Seisser. No doubt hopeful of signing a sensational book with high sales, various publishers offered their services to Hitler, either in person or by letter. In time, however, the emphasis of the work changed again, probably in part thanks to some sort of explicit or implicit bargain with the Bavarian state to let sleeping dogs lie in return for a mild sentence. There were also positive reasons, however, for the new approach. Hitler wanted to use the relative peace of Landsberg to write a much broader manifesto elaborating the principles of National Socialism, charting a path to power for the movement and showing how Germany could regain her independence and great power status. The first volume of Mein Kampf, most of which was written or compiled in Landsberg, seems to have been largely a solo effort, with relatively little input from others. Julius Schaub, another inmate who later became his personal adjutant, recalled that Hitler wrote Mein Kampf ‘alone and without direct input from anyone’, not even Hess, who had joined him in Landsberg. Hitler typed the book himself, reading out or summarizing large sections to his fellow prisoners, who constituted an appreciative or at any rate a captive audience. Sometimes, he was moved to tears by his own words.

Incarceration gave Hitler a chance to read more widely and gather his thoughts. One of his main preoccupations in Landsberg was the United States, which he was corning to regard as the model state and society, perhaps even more so than the British Empire. ‘He ‘devoured’ the memoirs of a returned German emigrant to the United States. ‘One should take America as a model,’ he proclaimed. Hess wrote that Hitler was captivated by Henry Ford’s methods of production which made automobiles available to the ‘broad mass’ of the people. This appears to have been the genesis of the Volkswagen. Hitler envisaged that the automobile would further serve as ‘the small man’s means of transport into nature—as in America’. He also planned to apply methods of mass production to housing, and experimented with designs for a Volkshaus for families with three to five children which would have five rooms and a bathroom with a garage in large terraced settlements. He was equally determined not be outdone in the construction of ‘skyscrapers’, and looked forward to the consternation of the ‘Deutsch-Völkisch’ elements by putting the party headquarters into such an edifice. Quite apart from showing that Hitler had an interest in vernacular architecture, and not just in monumental public buildings, these plans prove that he was thinking of elevating the condition of the German working class through American style suburban and metropolitan modernity. This was the model of an ideal society against which he wrote Mein Kampf.

Modernity was not an end in itself, but a means by which the German people, especially the German working class and German women, could be mobilized in support of the project of national revival. Hitler exalted technological development—aeroplanes, typewriters, telephones and suspension bridges, and even domestic appliances. These would free German women from drudgery and enable them to be better wives producing more children. ‘How little our poor women benefit from progress,’ he lamented, ‘there is so much one can do to make [a woman’s life] easier with the help of technology! But most people still think today that a woman is only a good housewife if she is constantly dirty and working from early until late.’ ‘And then,’ Hitler continued, ‘one is surprised when the woman is not intellectual enough for the man, when he cannot find stimulation and recuperation.’ Worse still, he went on, this was ‘bad for the race’ because it was ‘obvious that his overtired wife will not have as healthy children as one who is well rested, can read good books and so on’. The link between what Hitler would later call the racial ‘elevation’ of Germany, technological progress and maintaining the standard of living is already evident here.

Part and parcel of this programme of racial improvement was Hitler’s support for what we would today call ‘alternative’ technology. ‘Every farm,’ he demanded, ‘which does not possess any alternative source of energy’ should set up a ‘wind motor with dynamo and rechargeable batteries’. This might not be possible in the current economic climate, Hitler continued., but it would be a viable long-term investment. He rejected the idea that technological change took the romance out of farming. ‘I couldn’t care less about a romanticism,’ he exclaimed, ‘which puts people behind frosted windows in the twilight, [and] which lets women age prematurely through hard work’. Hitler therefore sneered at the city folk who went into the country for a day, enthused about the scenery and then returned to their modem and efficient homes in the city. Hitler claimed to support ‘the preservation of nature’, but in his view it should take the form of national parks in the mountains. ‘Here too,’ Hitler concluded, ‘the Americans have made the right choice with their Yellowstone Park.’

In Landsberg, Hitler did not abate his ferocious hostility to international finance capitalism. He did, however, qualify some of his earlier ideas about ‘national’ economies. Significantly, he rejected the demands of the German automobile manufacturers to be protected against competition from Henry Ford through higher tariff barriers. ‘Our industry needs to exert itself and achieve the same performance,’ Hitler remarked. Once again, the United States was the explicit model.

Hitler was also taking on board the concept of Lebensraum. This was one of the key ideas of Hess’s teacher and patron Karl Haushofer, the doyen of German Geopolitik. He visited Hess in prison, bringing him copies of Clausewitz and Friedrich Ratzel’s ‘Political Geography’, one of the seminal geopolitical texts. While there is no hard evidence that Haushofer met Hitler on those occasions it is highly likely he did so, or at any rate that his ideas found their way to him. In mid July, there was a debate about Lebensraum at Landsberg, which began with some good-natured joshing in the garden and ended with Hitler’s ‘marvelling’ inner circle being provided with a lengthy definition of the term by Hess. Its essence was simple: every people required a certain ‘living space’ to feed and accommodate its growing population. The idea seemed to provide the answer to the main challenge facing the Reich, which was the emigration of its demographic surplus to the United States. This was part of an important shift in Hitler’s thinking, away from a potential Russo German alliance and the prevention of emigration through the restitution of German colonies, towards the capture of Lebensraum in the east, contiguous to an expanded German Reich. It had less to do with hatred of Bolshevism and eastern European Jewry, and more to do with the need to prepare the Reich for a confrontation or equal coexistence with an Anglo-America whose dynamism mesmerized Hitler more than ever.

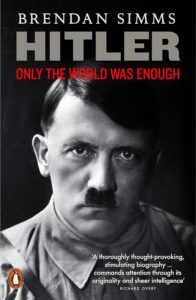

From 18 November 2023 until 12 January this year I had been publishing some extracts from Brendan Simms’ book on Hitler. I will no longer quote it at length. But I have just edited a PDF that can serve not only as an introduction to Simms’s intellectual biography—in the sense of trying to understand Hitler’s ideas— but for something more important.

From 18 November 2023 until 12 January this year I had been publishing some extracts from Brendan Simms’ book on Hitler. I will no longer quote it at length. But I have just edited a PDF that can serve not only as an introduction to Simms’s intellectual biography—in the sense of trying to understand Hitler’s ideas— but for something more important.