So far, I have only quoted a few paragraphs from the chapters of Tom Holland’s book. But the ‘Woe to You Who Are Rich’ section of the ‘Enlightenment’ chapter is so important that I will quote it in full.

That section shows no more and no less how Christianity metamorphosed into neochristianity: the mental virus that has been infecting the white man since the American Revolution and the French Revolution: two sides of the same coin, as we shall see in this post.

It took effort to strip bare a basilica as vast as the one that housed Saint Martin. For a millennium and more after the great victory won by Charles Martel over the Saracens, it had continued to thrive as a centre of pilgrimage. A succession of disasters—attacks by Vikings, fires—had repeatedly seen it rebuilt. So sprawling had the complex of buildings around the basilica grown that it had come to be known as Martinopolis. But revolutionaries, by their nature, relished a challenge. In the autumn of 1793, when bands of them armed with sledgehammers and pickaxes occupied the basilica, they set to work with gusto. There were statues of saints to topple, vestments to burn, tombs to smash. Lead had to be stripped from the roof, and bells removed from towers. ‘A sanctuary can do without a grille, but the defence of the Fatherland cannot do without pikes.’ So efficiently was Martinopolis stripped of its treasures that within only a few weeks it was bare. Even so—the state of crisis being what it was—the gaunt shell of the basilica could not be permitted to go to waste. West of Tours, in the Vendée, the Revolution was in peril. Bands of traitors, massed behind images of the Virgin, had risen in revolt. Patriots recruited to the cavalry, when they arrived in Tours, needed somewhere to keep their horses. The solution was obvious. The basilica of Saint Martin was converted into a stable.

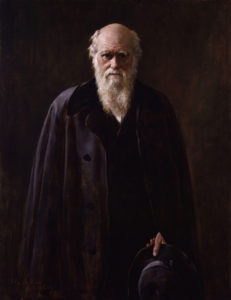

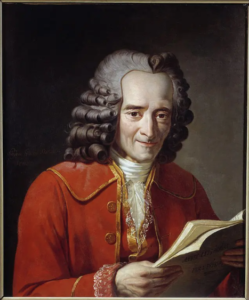

Horse shit steaming in what had once been one of the holiest shrines in Christendom gave to Voltaire’s contempt for l’infâme a far more pungent expression than anything that might have been read in a salon. The ambition of France’s new rulers was to mould an entire ‘people of philosophes’. The old order had been weighed and found wanting. The monarchy itself had been abolished. The erstwhile king of France—who at his coronation had been anointed with oil brought from heaven for the baptism of Clovis, and girded with the sword of Charlemagne—had been executed as a common criminal. His decapitation, staged before a cheering crowd, had come courtesy of the guillotine, a machine of death specifically designed by its inventor to be as enlightened as it was egalitarian. Just as the king’s corpse, buried in a rough wooden coffin, had then been covered in quicklime, so had every division of rank in the country, every marker of aristocracy, been dissolved into a common citizenship. It was not enough, though, merely to set society on new foundations. The shadow of superstition reached everywhere. Time itself had to be recalibrated. That October, a new calendar was introduced. Sundays were swept away. So too was the practice of dating years from the incarnation of Christ. Henceforward, in France, it was the proclamation of the Republic that would serve to divide the sweep of time.

Even with this innovation in place, there still remained much to be done. For fifteen centuries, priests had been leaving their grubby fingerprints on the way that the past was comprehended. All that time, they had been carrying ‘pride and barbarism in their feudal souls’. And before that? A grim warning of what might happen should the Revolution fail was to be found in the history of Greece and Rome. The radiance that lately had begun to dawn over Europe was not the continent’s first experience of enlightenment. The battle between reason and unreason, between civilisation and barbarism, between philosophy and religion, was one that had been fought in ancient times as well. ‘In the pagan world, a spirit of toleration and gentleness had ruled.’ It was this that the sinister triumph of Christianity had blotted out. Fanaticism had prevailed. Now, though, all the dreams of the philosophes were coming true. L’infâme was being crushed. For the first time since the age of Constantine, Christianity was being targeted by a government for eradication. Its baleful reign, banished on the blaze of revolution, stood revealed as a nightmare that for too long had been permitted to separate twin ages of progress: a middle age.

This was an understanding of the past that, precisely because so flattering to sensibilities across Europe, was destined to prove infinitely more enduring than the makeshift calendar of the Revolution. Nevertheless, just like many other hallmarks of the Enlightenment, it did not derive from the philosophes. The understanding of Europe’s history as a succession of three distinct ages had originally been popularised by the Reformation. To Protestants, it was Luther who had banished shadow from the world, and the early centuries of the Church, prior to its corruption by popery, that had constituted the primal age of light. By 1753, when the term ‘Middle Ages’ first appeared in English, Protestants had come to take for granted the existence of a distinct period of history: one that ran from the dying years of the Roman Empire to the Reformation. The revolutionaries, when they tore down the monastic buildings of Saint-Denis, when they expelled the monks from Cluny and left its buildings to collapse, when they reconsecrated Notre Dame as a ‘Temple of Reason’ and installed beneath its vaulting a singer dressed as Liberty, were paying unwitting tribute to an earlier period of upheaval. In Tours as well, the desecration visited on the basilica was not the first such vandalism that it had suffered. Back in 1562, when armed conflict between Catholics and Protestants had erupted across France, a band of Huguenots had torched the shrine of Saint Martin and tossed the relics of the saint onto the fire. Only a single bone and a fragment of his skull had survived. It was hardly unsurprising, then, in the first throes of the Revolution, that many Catholics, in their bewilderment and disorientation, should initially have suspected that it was all a Protestant plot.

In truth, though, the origins of the great earthquake that had seen the heir of Clovis consigned to a pauper’s grave extended much further back than the Reformation. ‘Woe to you who are rich.’ Christ’s words might almost have been the manifesto of those who could afford only ragged trousers, and so were categorised as men ‘without knee-breeches’: sans-culottes. They were certainly not the first to call for the poor to inherit the earth. So too had the radicals among the Pelagians, who had dreamed of a world in which every man and woman would be equal; so too had the Taborites, who had built a town on communist principles, and mockingly crowned the corpse of a king with straw; so too had the Diggers, who had denounced property as an offence against God. Nor, in the ancient city of Tours, were the sans-culottes who ransacked the city’s basilica the first to be outraged by the wealth of the Church, and by the palaces of its bishops. In Marmoutier, where Alcuin had once promoted scripture as the inheritance of all the Christian people, a monk in the twelfth century had drawn up a lineage for Martin that cast him as the heir of kings and emperors—and yet Martin had been no aristocrat. The silken landowners of Gaul, offended by the roughness of his manners and his dress, had detested him much as their heirs detested the militants of revolutionary France. Like the radicals who had stripped bare his shrine, Martin had been a destroyer of idols, a scorner of privilege, a scourge of the mighty. Even amid all the splendours of Martinopolis, the most common depiction of the saint had shown him sharing his cloak with a beggar. Martin had been a sans-culotte.

There were many Catholics, in the first flush of the Revolution, who had recognised this. Just as English radicals, in the wake of Charles I’s defeat, had hailed Christ as the first Leveller, so were there enthusiasts for the Revolution who saluted him as ‘the first sans-culotte’. Was not the liberty proclaimed by the Revolution the same as that proclaimed by Paul? ‘You, my brothers, were called to be free.’ This, in August 1789, had been the text at the funeral service for the men who, a month earlier, had perished while storming the Bastille, the great fortress in Paris that had provided the French monarchy with its most intimidating prison. Even the Jacobins, the Revolution’s dominant and most radical faction, had initially been welcoming to the clergy. For a while, indeed, priests were more disproportionately represented in their ranks than any other profession. As late as November 1791, the president elected by the Paris Jacobins had been a bishop. It seemed fitting, then, that their name should have derived from the Dominicans, whose former headquarters they had made their base. Certainly, to begin with, there had been little evidence to suggest that a revolution might precipitate an assault on religion.

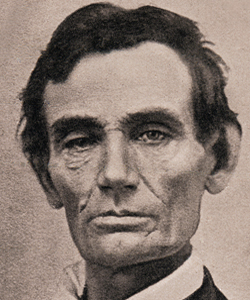

And much from across the Atlantic to suggest the opposite. There, thirteen years before the storming of the Bastille, Britain’s colonies in North America had declared their independence. A British attempt to crush the revolution had failed. In France—where the monarchy’s financial backing of the rebels had ultimately contributed to its own collapse—the debt of the American revolution to the ideals of the philosophes appeared clear. There were many in the upper echelons of the infant republic who agreed. In 1783, six years before becoming their first president, the general who had led the colonists to independence hailed the United States of America as a monument to enlightenment. ‘The foundation of our Empire,’ George Washington had declared, ‘was not laid in the gloomy age of Ignorance and Superstition, but at an Epoch when the rights of mankind were better understood and more clearly defined than at any former period.’ This vaunt, however, had implied no contempt for Christianity. Quite the opposite. Far more than anything written by Spinoza or Voltaire, it was New England that had provided the American republic with its model of democracy, and Pennsylvania with its model of toleration. That all men had been created equal, and endowed with an inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, were not remotely self-evident truths. That most Americans believed they were owed less to philosophy than to the Bible: to the assurance given equally to Christians and Jews, to Protestants and Catholics, to Calvinists and Quakers, that every human being was created in God’s image. The truest and ultimate seedbed of the American republic—no matter what some of those who had composed its founding documents might have cared to think—was the book of Genesis.

The genius of the authors of the United States constitution was to garb in the robes of the Enlightenment the radical Protestantism that was the prime religious inheritance of their fledgling nation. When, in 1791, an amendment was adopted which forbade the government from preferring one Church over another, this was no more a repudiation of Christianity than Cromwell’s enthusiasm for religious liberty had been. Hostility to imposing tests on Americans as a means of measuring their orthodoxy owed far more to the meeting houses of Philadelphia than to the salons of Paris. ‘If Christian Preachers had continued to teach as Christ & his Apostles did, without Salaries, and as the Quakers now do, I imagine Tests would never have existed.’ So wrote the polymath who, as renowned for his invention of the lightning rod as he was for his tireless role in the campaign for his country’s independence, had come to be hailed as the ‘first American’. Benjamin Franklin served as a living harmonisation of New England and Pennsylvania. Born in Boston, he had run away as a young man to Philadelphia; a lifelong admirer of Puritan egalitarianism, he had published Benjamin Lay; a strong believer in divine providence, he had been shamed by the example of the Quakers into freeing his slaves. If, like the philosophes who much admired him as an embodiment of rugged colonial virtue, he dismissed as idle dogma anything that smacked of superstition, and doubted the divinity of Christ, then he was no less the heir of his country’s Protestant traditions for that. Voltaire, meeting him in Paris, and asked to bless his grandson, had pronounced in English what he declared to be the only appropriate benediction: ‘God and liberty.’ Franklin, like the revolution for which he was such an effective spokesman, illustrated a truth pregnant with implications for the future: that the surest way to promote Christian teachings as universal was to portray them as deriving from anything other than Christianity.

In France, this was a lesson with many students. There, too, they spoke of rights. The founding document of the country’s revolution, the sonorously titled ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen’, had been issued barely a month after the fall of the Bastille. Part-written as it was by the American ambassador to France, it drew heavily on the example of the United States. The histories of the two countries, though, were very different. France was not a Protestant nation. There existed in the country a rival claimant to the language of human rights. These, so it was claimed by revolutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic, existed naturally within the fabric of things, and had always done so, transcending time and space. Yet this, of course, was quite as fantastical a belief as anything to be found in the Bible. The evolution of the concept of human rights, mediated as it had been since the Reformation by Protestant jurists and philosophes, had come to obscure its original authors. It derived, not from ancient Greece or Rome, but from the period of history condemned by all right-thinking revolutionaries as a lost millennium, in which any hint of enlightenment had at once been snuffed out by monkish, book-burning fanatics. It was an inheritance from the canon lawyers of the Middle Ages.

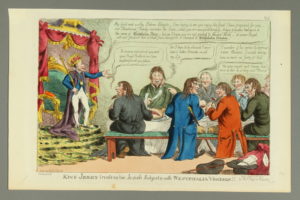

Nor had the Catholic Church—much diminished though it might be from its heyday—abandoned its claim to a universal sovereignty. This, to revolutionaries who insisted that ‘the principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation’, could hardly help but render it a roadblock. No source of legitimacy could possibly be permitted that distracted from that of the state. Accordingly, in 1791—even as legislators in the United States were agreeing that there should be ‘no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof’—the Church in France had been nationalised. The legacy of Gregory VII appeared decisively revoked. Only the obduracy of Catholics who refused to pledge their loyalty to the new order had necessitated the escalation of measures against Christianity itself. Even those among the revolutionary leadership who questioned the wisdom of attempting to eradicate religion from France never doubted that the pretensions of the Catholic Church were insupportable. By 1793, priests were no longer welcome in the Jacobins. That anything of value might have sprung from the mulch of medieval superstition was a possibility too grotesque even to contemplate. Human rights owed nothing to the flux of Christian history. They were eternal and universal—and the Revolution was their guardian. ‘The Declaration of Rights is the Constitution of all peoples, all other laws being variable by nature, and subordinated to this one.’

The Declaration of the Rights of Man

portrayed as though delivered on

tablets of stone from Mount Sinai.

So declared Maximilien Robespierre, most formidable and implacable of the Jacobin leaders. Few men were more icily contemptuous of the claims on the future of the past. Long an opponent of the death penalty, he had worked fervently for the execution of the king; shocked by the vandalising of churches, he believed that virtue without terror was impotent. There could be no mercy shown the enemies of the Revolution. They bore the taint of leprosy. Only once they had been amputated, and their evil excised from the state, would the triumph of the people be assured. Only then would France be fully born again. Yet there hung over this a familiar irony. The ambition of eliminating hereditary crimes and absurdities, of purifying humanity, of bringing them from vice to virtue, was redolent not just of Luther, but of Gregory VII. The vision of a universal sovereignty, one founded amid the humbling of kings and the marshalling of lawyers, stood recognisably in a line of descent from that of Europe’s primal revolutionaries. So too their efforts to patrol dissidence. Voltaire, in his attempt to win a pardon for Calas, had compared the legal system in Toulouse to the crusade against the Albigensians. Three decades on, the mandate given to troops marching on the Vendée, issued by self-professed admirers of Voltaire, echoed the crusaders with a far more brutal precision. ‘Kill them all. God knows his own.’ Such was the order that the papal legate was reputed to have given before the walls of Béziers. ‘Spear with your bayonets all the inhabitants you encounter along the way. I know there may be a few patriots in this region—it matters not, we must sacrifice all.’ So the general sent to pacify the Vendée in early 1794 instructed his troops. One-third of the population would end up dead: as many as a quarter of a million civilians. [see, e.g., this Wikipedia article—Ed.]

Meanwhile, back in the capital, the execution of those condemned as enemies of the people was painted by enthusiasts for revolutionary terror in recognisably scriptural colours. Good and evil locked in a climactic battle, the entire world at stake; the damned compelled to drink the wine of wrath; a new age replacing the old: here were the familiar contours of apocalypse. When, demonstrating that its justice might reach even into the grave, the revolutionary government ordered the exhumation of the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis, the dumping of royal corpses into lime pits was dubbed by those who had commissioned it the Last Judgement.

The Jacobins, though, were not Dominicans. It was precisely the Christian conviction that ultimate judgement was the prerogative of God, and that life for every sinner was a journey towards either heaven or hell, that was the object of their enlightened scorn. Even Robespierre, who believed in the eternity of the soul, did not on that count imagine that justice should be left to the chill and distant deity that he termed the Supreme Being. It was the responsibility of all who cherished virtue to work for its triumph in the here and now. The Republic had to be made pure. To imagine that a deity might ever perform this duty was the rankest superstition. In the Gospels, it was foretold that those who had oppressed the poor would only receive their due at the end of days, when Christ would return in glory, and separate ‘the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats’. But this would never happen. A people of philosophes could recognise it to be a fairy tale. So it was that the charge of sorting the goats from the sheep, and of delivering them to punishment, had been shouldered—selflessly, grimly, implacably—by the Jacobins.

This was why, in the Vendée, there was no attempt to do as the friars had done in the wake of the Albigensian crusade and apply to a diseased region a scalpel rather than a sword. It was why as well, in Paris, the guillotine seemed never to take a break from its work. As the spring of 1794 turned to summer, so its blade came to hiss ever more relentlessly, and the puddles of blood to spill ever more widely across the cobblestones. It was not individuals who stood condemned, but entire classes. Aristocrats, moderates, counter-revolutionaries of every stripe: all were enemies of the people.

Holland fails to mention something vital: the revolutionaries took it upon themselves to guillotine blond Frenchmen in particular. See the chapters on the French Revolution in the histories of the white race from the pens of William Pierce and Arthur Kemp.