by Evropa Soberana

The destruction of the Greco-Roman World – 1

(Fourth century)

After the Council of Nicaea, Christianity reaches a doctrinal uniformity that unifies the diverse factions, and acquires a legal administrative character, like a state within the State. Nicaea, incidentally, is a city in the province of Bithynia, Asia Minor (now Turkey). Constantine brings together 318 bishops, each elected by their community, to debate and establish a ‘Christian normalization’, in view of the many factions and discrepancies within the religion. The result is the so-called ‘Nicene creed’: the Christianity to preach.

By this time, the emperor needs a force of union for the melting pot of races that has been imposed in Rome. There were many ‘salvation cults’ with rites practiced in secret, mostly of the underground type of cults that always arise in times of decadence and degeneration.

There is the cult of Mithras (a cult of Iranian origin and military character, already corrupted by the masses, although during an ascending era it was popular in the Roman legions), and the cult of Cybele. The emperor chose Christianity for his empire, not because of its value as a religion, but because of its Semitic intolerance; its fanaticism—famous throughout the empire—, its centuries-old experience as a tool of intrigue, its intelligence networks and its equalizing, proselytising and globalising ethos make it the perfect ‘emergency religion’.

The other religions, lacking of intolerance, will not impose themselves by violence on reluctant people with that unifying effect of flock of sheep that Christianity will provide. And what the unwise Constantine needs is precisely a flock, not a combination of different people each with its own identity. Christianity, therefore, slightly prolongs the agony of the Roman Empire. People begin to convert to Christianity by snobbishness and climbing eagerness, to reach high positions: that is, to make a career.

After a thousand intrigues, conspiracies, factional fights, poisonings, manipulations and blackmail, the Edict of Milan gives Christianity the consideration of ‘respectable’ religion, giving it clearance. Its former creeping humility disappears and the most unpleasant Christian face arises: Christians immediately demand that the ‘idol-worshipers’ be prescribed the bestial punishments described in the Old Testament.

324

Throughout Italy, with the exception of Rome, the temples of Jupiter are closed. In Didyma, Asia Minor, the sanctuary of the Oracle of Apollo is sacked. Priests are sadistically tortured to death. Constantine expelled the Hellenists from Mount Athos (a mystical zone of classical Greece that later became an important Christian-Orthodox centre), destroying all the Hellenic temples in the area. In 324, Constantine, brainwashed by his mother Helena, ordered to destroy the temple of the god Asclepius in Cilicia, as well as numerous temples of the goddess Aphrodite in Jerusalem, Afak (Lebanon), Mamre, Phoenicia, Baalbek, and other places.

326

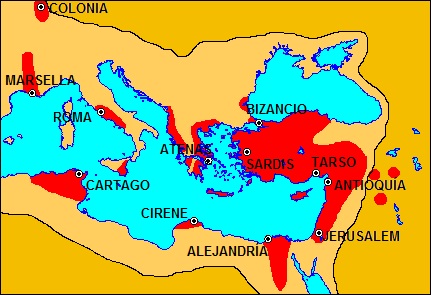

Constantine changes the capital of his empire to Byzantium, which he renames with the name Nuova Roma. This, together with the adoption of Christianity, means a radical change within the Roman Empire. From then on, the Roman focus of cultural attention changes from its origin in northern Europe and Greece, to Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine and North Africa (the Eastern Mediterranean, from which most of the inhabitants of the Empire now come): importing models of dark Semitic beauty unthinkable for the ancient Romans who, like the Greeks, had the Nordic beauty in high esteem as a sign of noble and divine origin.

330

Constantine steals statues and treasures from Greece to decorate Nuova Roma (later Constantinople), the new capital of his empire. At this same time, a bishop from Caesarea, Asia Minor, later known as St. Basil who is credited with grandiose phrases such as ‘I wept for my miserable life’, laid the foundations of what would later become the Orthodox Church.

337

On his deathbed, Emperor Constantine I is baptized a Christian, becoming the first Christian Roman emperor. The Judeo-Christian sycophants, wanting to make clear what example of emperor he was, will call him Constantine I ‘the Great’ and ‘Saint Constantine’.

341

Emperor Flavius Julius Constantius (reigned 337 to 361), another fanatical Christian, proclaims his intention to persecute ‘all fortune-tellers and pagans’. Thus, many Greek Hellenists are imprisoned, tortured and executed. Around this time, famous Christian leaders such as Marcus of Arethusa or Cyril of Heliopolis do their way, particularly demolishing temples, burning important writings and persecuting the Hellenists who, in some way, threaten the expansion of the incipient Church.

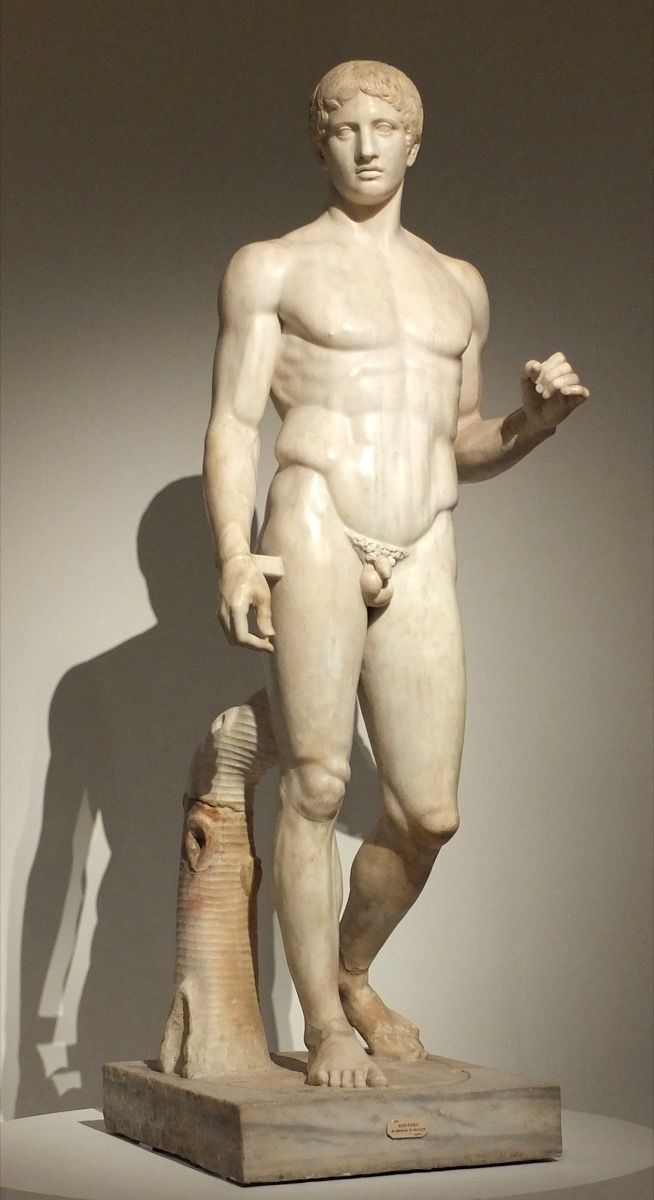

We cannot doubt that, at least in part, Christianity used its repugnance for Roman decadence to persecute any Greco-Roman cult, just as Islam today rejects the decline of Western Civilization. This was just the perfect excuse how Christianity justified its deeds and exterminated classical culture. That which Christianity systematically persecuted with shameful excuses, was something pure and aristocratic: luminous Hellenism, love of gnosis, art, philosophy, free debate and the natural sciences. It was Egyptian, Greek and Persian knowledge. What Christianity was doing with its persecution and extermination was literally erasing the traces of the gods.

346

Another great anti-Hellenistic persecution in Constantinople. The famous anti-Christian author and speaker Libanius[1] is accused of being a ‘magician’ and is banished. At this point, what was once the Roman Empire has gone crazy, chaotic and unrecognisable. The patriotic Romans must take their hands to their heads when they see how ignorant crowds snatch from their heirs all the harvest of the classic cultures, not only of Rome itself, but also of Egypt, Persia and Greece.

353-354

The Decree of Constantius establishes the death penalty for anyone who practices a religion with ‘idols’. Another decree, in 354, orders to close all the Greco-Roman temples. Many of them are assaulted by fanatical crowds, who torture and murder the priests, loot the treasures, burn the writings, destroy works of art that today would be considered sublime and destroy everything in general.

Most of the temples that fall in this era are desecrated, being converted into stables, brothels and gambling halls. The first lime factories are installed next to these closed temples, from which they extract their raw material—in such a way that a large part of classical sculpture and architecture is transformed into lime!

In this same year of 354, a new edict plainly orders destruction of all Greco-Roman temples and the extermination of all ‘idolaters’. The killings of the adepts of Greco-Roman culture, the demolitions of their temples, the destructions of statues and the fires of libraries throughout the empire follow each other.

This statue of Emperor Augustus—the first Roman emperor,

who was obviously pagan—was disfigured by the Christians,

who engraved a cross on the forehead.

Let us not make the mistake of blaming the Christianised Roman emperors. They were ridiculous and weak men, but they were in the hands of their educators. The instructors, who respond to the type of vampiric and parasitic priest so hated by Nietzsche, were the true leaders of the meticulous and massive destruction that was taking place.

The numerous bishops and saints to whom we have referred were ‘cosmopolitan’ men of Jewish education, many of whom had been born in Judea, or came from essentially Jewish areas. They were transformed Jews who, having come in contact with their enemies, studying them carefully and hatefully, knew how to destroy them.

They had a broad rabbinical education and knew in depth the teachings of classical culture, dominating the Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, Syrian and Egyptian languages. Such characters, of an intelligence and a cunning as outstanding as their resentment, were convinced that they were building a new order, and that to do so it was necessary to erase a hundred percent every trace of any previous civilisation, and any thought that was not of Jewish origin. We must recognise that their psychological knowledge and their mastery of propaganda were of a very high level.

356

All the rituals of classical culture are placed outside the law and punished by death. A year later, all methods of divination, including astrology, are also proscribed.

359

In the very Jewish city of Scythopolis, (province of Syria, today corresponds to Beit She’an, in Israel), Christian leaders organise nothing more and nothing less than a concentration camp for the Hellenists detained throughout the empire. In this field those who profess classical beliefs, or who simply opposed the Church, are imprisoned, tortured and executed.

Over time, Scythopolis becomes a whole infrastructure of camps, dungeons, torture cells and execution rooms, where thousands of Hellenists would go. The most intense horrors of the time take place here. It was the gulag that the communism of the time used to suppress the dissidents.[2]

________________

[1] Note of the Editor: Libanius is a kind of hero in Gore Vidal’s historical novel, Julian.

[2] Note of the Editor: Unlike Karlheinz Deschner, who uses thousands of footnotes in his books about the criminal history of Christianity, Evropa Soberana does not reference most of what he writes. I guess his source for the Judaeo-Christian death camp in Scythopolis was Ammianus Marcellinus, but the Wikipedia article on Ammianus does not mention the camps because the wiki is run by Jews and philo-Semite whites.

Scholars of the 14 words really need to start building a library in Greek and Latin that includes the collection of the Loeb Classical Library to properly reference these historical tragedies so difficult to find without a proper bibliographical guide.