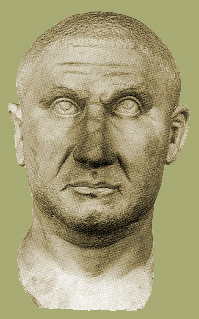

Emperor Julian

(Flavius Claudius Iulianus Augustus)

Caesar: 6 November 355 – February 360

Augustus: February 360 – 3 November 361

Sole Augustus: 3 November 361 – 26 June 363

The pagan reaction under Julian

Like his brother Gallus, Julian was also spared from the killing of relatives, although as a member of the imperial dynasty he was kept closely guarded: first in a magnificent estate of Nicomedia, which had been owned by his mother (Basilina, deceased shortly after the birth of Julian), and then in the lonely fortress of Macellum, located in the heart of Anatolia, where his older brother was also imprisoned. The distrustful emperor wove a dense network of spies around both princes, to transmit him each and every one of their words.

They lived ‘like prisoners in that Persian castle’ (Julian), practically arrested and surely threatened with death. In Nicomedia, Julian was given a preceptor, Bishop Eusebius, a relative of Basilina, ecclesiastic and man of the world already known at the time, who, following the custom of Oriental prelates, used to dye his nails with cinnabar and his hair with henna. He was instructed to educate the child severely in the Christian religion; to prevent him from contacting the population, and to ‘never talk about the tragic end of his family’, although at seven Julian was very aware of it and this caused frequent crying spells and terrible nightmares.

In Macellum, where he was confined for seven years with scarcely any other company than that of his slaves, he had as his educator the Arian Jorge of Cappadocia, who was in charge of training him for the priesthood. But then Julian was able to leave the place and settled in Constantinople, where he lived the disputes between Arians and Orthodox and knew the real life of that world of violent riots and fiery mutual excommunications. Towards the end of 351, when Julian was twenty years old, Constantius ordered him to continue his studies in Nicomedia. Julian visited Pergamum, Ephesus and Athens, where he had notable teachers who won him for paganism.

Appointed caesar in 355 by Constantius, and proclaimed augustus by the army in Paris in 360, the same sovereign, who had no offspring, at the time of death appointed Julian as successor… when the two opposing armies marched to the encounter of the other. An ephemeral restoration of polytheistic traditions took place, with the establishment of a Hellenistic ‘state religion’, whose organization followed in many respects the pattern of Christian canons.

Julian tried to replace the cross and the nefarious dualism of Christians by a formula composed of certain streams of Hellenistic philosophy and a ‘solar pantheism’. Without neglecting the other gods of the pagan pantheon, he had a temple built for the Sun god—probably identified with Mithra—in the imperial palace; on numerous occasions he proclaimed his veneration for the basileus Helios, the Sun king, which was already a bi-millennial tradition:

Since my childhood, I was inspired by an invincible longing for the rays of the God, who have always captivated my soul, in such a way that I constantly wanted to contemplate it and even at night, when I was in the country, I forgot everything to admire the beauty of starry heaven…

Today we have become accustomed to interpreting Julian’s reaction as a nostalgic movement, a romantic anachronism or the absurd attempt to turn the hands of the clock backwards. But why do we interpret it that way? Was he refuted, or could he be, instead of being drowned in blood? What is certain and undeniable is that Emperor Julian (from 361 to 363), called ‘the Apostate’ by the Christians, was far superior to his Christian predecessors in character, morality and spirituality.

Trained in philosophy and literature, not only was he ‘the first truly cultured emperor for more than a century’ (Brown), but also deserved ‘a prominent place among writers of the time in the Greek language’ (Stein), and he knew to surround himself with the best thinkers of his time. Julian was zealous in the fulfilment of his duty and enemy of all gentleness, since he never had mistresses or ephebes, never got drunk; the emperor went to work since dawn. He tried to rationalise the bureaucracy and place intellectuals in top government and administrative positions.

Julian abolished the splendours of the court, the possession of eunuchs and jesters, and the whole system of flatterers, parasites, spies and whistleblowers who were fired by the thousands. He reduced the service, reduced the taxes by a fifth, acted with severity against the unfaithful collectors and sanitized the state mail. He also abolished the labarum, that is, the banner of the army with the anagram of Christ, and tried to resurrect ancient cults, festivals and the Paideia: classical education. He ordered the return of the old temples or the reconstruction of those that had been destroyed, and even the return of the statues and other sacred ornaments that adorned the gardens of the individuals who had appropriated them.

But he did not ban Christianity; on the contrary, he allowed the return of the exiled clerics, which only served to foment new conspiracies and tumults.

The Donatists of Africa, while praising the emperor as a paragon of justice, disinfected their newly recovered churches by scrubbing them up and down with sea water, sanded the wood of the altars and the plaster of the walls, regained the influence lost under Constans and Constantius II, and prepared to enjoy their revenge. The Catholics were converted by force, their churches expropriated, their books burned, their chalices and monstrances thrown by the windows and the hosts thrown to the dogs; some abused clerics died. Up to 391, the Donatists continued to have high status, at least in Numidia and Mauritania.

It is true that Julian, as a supporter of polytheism, criticized the Old Testament and its monotheistic rigours, as well as the arrogance of the supposed chosen people, but he granted Yahweh a rank equal to that of the other gods and even admitted that the God worshiped by the Jews was ‘the best and most powerful of all’. A Jewish delegation that visited him in Antioch in July 362, obtained the authorization to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem and the promise of new territories, in a kind of anticipation of the current ‘Zionism’, which motivated the jubilation of the diaspora. The reconstruction of the temple was initiated with great eagerness the following spring, while Julian undertook his campaign in Persia, but towards the end of May a fire, judged ‘providential’ by the Christians, as well as the death of Julian, meant the end of the works forever.

Julian was always in favour of tolerance, even towards Christians. If his dispositions regarding the ‘Galileans’, he said on one occasion, were benign and humanitarian, they should reciprocate by not bothering anyone, nor trying to impose assistance on their churches. In a letter to the citizens of Bosra, he wrote:

To convince and to teach men, it is necessary to use reason and not blows, threats or corporal punishment. I will not tire of repeating it: if you are sincere supporters of the true religion, you will refrain from bothering, attacking or offending the community of the Galileans, who are more worthy of pity than hatred, since they are wrong in matters of such power and transcendence.

Now, and although Julian was a supporter of tolerance… he could not avoid the use of violence against the violent, the Christians who were dedicated to desecrating and even destroying the newly rebuilt temples in Syria and Asia Minor, as well as statues. His legislation in the matter of education provoked many hatreds, inasmuch as he forbade Christians to study Greek literature (saying ‘let them stay in their churches interpreting their Matthew and Luke’). He also demanded the return of the columns and capital stolen from the temples by the Christians to adorn their ‘houses of God’.

If the Galileans want to have decoration in their temples, congratulations, but not with the materials belonging to other places of worship.

Libanius tells how the ships and chariots that returned their columns to the sacked gods could be seen everywhere. On October 22, 362, the Christians set fire to the temple of Apollo in Daphne, which had been restored by the sovereign, and destroyed the famous statue. In retaliation, Julian had the Basilica of Antioch and other churches consecrated to various martyrs razed. (Incidentally, Christians said that the temple had been struck by lightning but according to Libanius, there were no storm clouds on the night of the fire.)

In Damascus, Gaza, Ashkelon, Alexandria and other places the Christian basilicas burned, sometimes with the collaboration of the Jews; some believers were tortured or killed, including Bishop Marcus de Arethusa, so he entered the payroll of the martyrs. But, in general lines, ‘more offended had been the rights of the pagans’ (Schuitze), and in any case said pogrom was no more than a reaction to the excesses of the Christians, their abuses and their diatribes against paganism.

Throughout the empire, from Arabia and Syria, through Numidia, and even the Italian Alps, Julian was celebrated as a ‘benefactor of the state’, ‘undoing past wrongs’, ‘restorer of temples and the empire of freedom’, ‘magnanimous inspirer of the edicts of tolerance’. Even one of Julian’s main intellectual detractors, Gregory of Nazianzus, confessed that his ears ached from hearing so much praise from his liberal regime, according to Ernst Stein, ‘one of the healthiest the Roman Empire ever had’.

During the campaign in Persia, initiated by the emperor from Antioch (which was the main base of operations of the Romans against the Persians), on March 5, 363, a favourable occasion was presented. Julian, who was not wearing a breastplate, fell north of Ctesiphon, on the banks of the Tigris. Why was he unarmed? Was he wounded by an enemy spear or, as some claim, from his own ranks? Nobody knew.

Libanius, who was friend of Julian, assures that the author was a man ‘who refused to render cult to the Gods’. And even a Christian historian claims that Julian died at midnight on June 26, 363, when he was thirty-two years old and had governed for twenty months, victim of an assassin in the pay of the Christians…, a hero without blemish, naturally, who ‘perpetrated this audacious action in defence of God and religion’.

The Persians argued that he could not be one of their own, because they were out of range when the emperor was wounded in the midst of his troops. ‘Only one thing is certain’, Benoist-Méchin wrote, ‘and it is that he was not a Persian’, although he does not provide any definitive proof. ‘Be that as it may’, wrote Theodoret, father of the Church, ‘was he man or angel who wielded the sword, the truth is that he acted as the servant of the divine will’.