Editor’s note: According to Ramzpaul’s most recent video, about 70-80 percent of white nationalists are Christians. If true that explains why my donations have dramatically dropped in the last months. But even as an alienated priest of the 14 words I’ll continue to translate passages from Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums.

Why I do this? Just pay extra attention to the quoted words of Revilo Oliver in my recent ‘Darwin’s exterminationism’: ‘how suddenly the terminal symptoms of Christianity appeared, like the symptoms of the tertiary stage of syphilis, and destroyed our race’s mentality and vital instincts…’ (for due context, see also ‘The Red Giant’).

In previous instalments of Deschner’s first volume the subject was the ethos of the Christians before they reached control of the Roman Empire. Let’s now see how they behaved after controlling it. White nationalists may know the tamed form of Christianity that founded the US but ignore that, in Old World history, in any country over which Christianity held sway it murdered and tortured to the exact extent of its power.

______ 卐 ______

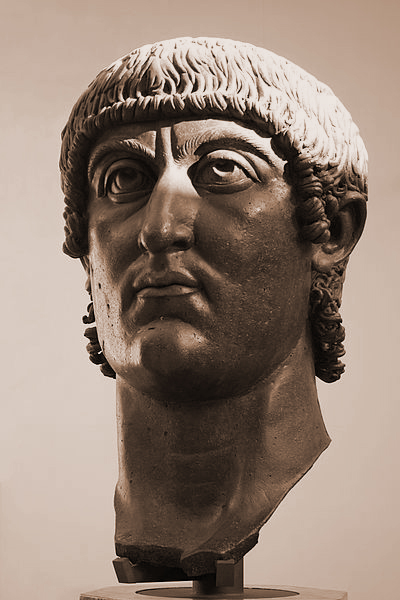

Chapter 5 – St. Constantine: The First Christian Emperor, ‘Symbol of Seventeen Centuries of Ecclesiastical History’

‘In all the wars he undertook and captained he achieved brilliant victories’. —St. Augustine, Father of the Church

‘Of all the Roman emperors, he alone honoured God, the Most High, with extraordinary devotion; he alone boldly announced the doctrine of Christ; he alone exalted his Church like no other since there is human memory; he alone put an end to the errors of polytheism and abolished all kinds of worship of idols’. —Eusebius of Caesarea, Bishop

‘Constantine was a Christian. He who works this way, and above all in a world that was still largely pagan, must be a Christian at heart and not only according to external demonstrations’. —Kurt Aland, theologian

‘Christendom always had before its eyes, as a luminous example, the figure of Constantine the Great’. —Peter Stockmeier, theologian

‘His spiritual postures were also those of a true believer’. —Karl Baus, theologian

‘That monster Constantine… This hypocritical and cold executioner who slaughtered his son, strangled his wife, murdered his father and his brother-in-law, and kept in his court a bunch of bloodthirsty and untamed priests…’ —Percy Bysshe Shelley

The terror of the Rhine

On July 25, 306, when Constantius I Chlorus died in Eboracum, present-day York (England) after a victory over the Picts, the troops appointed the young Constantine without delay. But Galerius, who tactically and formally remained as the first Augustus within the system of the Tetrarchy, only wanted to recognise Constantine as caesar.[1] That proclamation [Augustus status] had been an illegal act that broke the order of the second Tetrarchy.

The restoration of the holy religion was the first of his decrees. Once he became the owner of Britain and Gaul, in 310 he undertook the sacking of Spain, presumably to deprive Rome from the supply of Iberian cereals, and to expose Maxentius to a hungry population. But what Constantine most cultivated were the border wars, which made him the terror of all the Rhine.

His foreign policy ‘was characterized from the outset by its aggressiveness, as he lead his campaigns in counter-attacks and deep penetrations in enemy territory’ (Stallknecht). In 306 and 310 he decimated the Bructeri, stole their cattle, burned their villages and threw the prisoners into the circus to be pasture for wild beasts.

‘Of the prisoners, those who were not worth soldiers for not being reliable, nor for slaves for being too fierce, he threw all to the circus and were so many, that fatigued even the wild beasts’. The young emperor drowned in blood any attempt of rebellion; in 311 and 313 he crushed the Alemanni who had been greatly punished by his father, as well as the Franks, whose kings Ascaric and Merogaisus were destroyed by hungry bears, for general edification. The idolatrous Franks respected the life of the prisoners of war. But Constantine, after casting his victims (of the 71 well-known amphitheatres of antiquity, the Trier was tenth in importance, with 20,000 seats) and seeing the acceptance of the spectacle, decided to make it a permanent institution.

While the young ruler thus made life easier for the inhabitants of Trier, there were in the Roman Empire three other emperors: Maxentius in the West, who had authority over Italy and Africa; Maximinus Daia in the East, whose territory included the non-European part of the empire (all the provinces south of the Taurus mountain range and also Egypt), as well as Licinius, owner of the Danubian regions.

The fact that there were so many emperors seemed intolerable to Constantine, and he proposed to dismantle the system of the Tetrarchy instituted by Diocletian to consolidate that gigantic empire. So it began the destruction of the established ‘order’ by one warlike campaign after another, successively eliminating his rivals and establishing an ever-stronger bond between the empire and the Christian Church. Such a Constantinian ‘revolution’ was certainly a turning point in the history of Christianity, and it also brought about the rise of a new ruling class, the Christian clergy, while maintaining the old relations based on war and exploitation. It has been called ‘the beginning of the world metaphysical age’ (Thiess).

____________________

[1] Note of the Ed.: I am writing ‘caesar’ with small c to differentiate the title from ‘Augustus’. The difference between the caesars and the all-powerful Augustus will be explained in future instalments of the novel Julian.