Exactly a week ago Tom Goodrich passed away. I will observe one more day of silence in his memory because, unsurprisingly, the most popular websites of the racial right are not paying Tom any tribute…

Exactly a week ago Tom Goodrich passed away. I will observe one more day of silence in his memory because, unsurprisingly, the most popular websites of the racial right are not paying Tom any tribute…

Author: C .T.

Goodrich

In my previous post on Tom Goodrich, I said: ‘Only those who are knocked off the tower by their parents or guardians and become disabled, but are survivors, are able to cross the Wall in search of the raven’, tacitly referring to the metaphor of the featured post in this blog. I want to delve a little deeper into the subject. In a 2015 interview, Goodrich confessed early on:

Born in Kansas as Michael Thomas Schoenlein, I was adopted at age five. I spent my first years on my grandma’s farm in Missouri, then moved to Kansas. My biological dad was a professional musician, alcoholic and drug addict. About the age of 8-11, I was raped and sodomized on a daily basis. Other than that, I led a fairly normal childhood. After the military, I graduated from Washburn University in Kansas with a degree in history.

As every old visitor knows, I too was abused as a minor, but an even more serious abuse than sexual abuse: one of those that murder the soul (cf. Letter to mom Medusa; the next book, one I will soon begin translating into English, is entitled How to Murder Your Child’s Soul).

The vast majority of visitors to The West’s Darkest Hour imagine that these are parallel themes, Aryan preservation and the mistreatment of children (or adolescents, as was my case). But everything to do with the humanities, and indeed animals, is interrelated. For example, it will be recalled that this year I wrote some articles about Marco, a friend of the chess club whom I met half a century ago but recently visited and found him in a very clearly psychotic condition (I refer to what I wrote from the end of February to the beginning of March in six posts: #1, #2, #3, #4, #5 and #6). But the psychosis of this poor devil, who is not even able to make an appointment because of his malignant narcissism (cf. instalment #3), can be observed in millions of normal people.

Yesterday, for example, I watched a recent interview between the American John Mearsheimer and the Russian intellectual Alexander Dugin. From this point on in the conversation both Mearsheimer and Dugin spoke, without mentioning the term, of the malignant narcissism that currently afflicts the entire American elites, as incapable of putting themselves in the shoes of the Other as Marco. Dugin even mentioned a rather curious personal anecdote, that there are American politicians who are under the impression that chess is… a one-person game (!), presumably the American who plays solo ‘chess’.

In my soliloquies, I have said it to myself countless times: sometimes normal people are as psychotic as Marco, but the difference is that the latter lives on government charity and his first cousin. The narcissist in a psychotic state can no longer move in the real world on his own; the elites like those mentioned by Mearsheimer and Dugin can, which makes them infinitely more dangerous than the ordinary madman.

Marco had a mother who murdered his soul, though the disorder came very late in his life. Goodrich also had someone as abusive as Marco’s mother, but unlike him Goodrich not only survived psychologically but ennobled his soul to the extent of becoming an overman (the crow metaphor I use so much).

So, taking into account the recent conversation between Mearsheimer and Dugin, I could say that the two themes that have moved me to write are related: the psychic ravages of parental abuse, and deciphering why the white race is committing suicide: which includes the narcissistic American elites. In fact, I dare say that only people who, like Tom, were able to develop an emergent spin on their personal tragedy, have been able to see the historical past as it happened: and precisely for the reasons Tom mentioned in my post yesterday, to humbly listen to the voice of the vanquished.

Only a person who was internally broken, but who unlike millions of madmen didn’t succumb to psychosis (‘What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger!’) was able to understand what the German people suffered in WW2, even up to 1947 when the Allies were still perpetrating a Holocaust of defenceless Germans.

That man was Tom.

As one of the very fans who grasped George R.R. Martin’s philosophy said, passages I have quoted on this site:

Much like the audience, the seven kingdoms don’t understand what Bran has become, or how he helped save the world. Yet, when Bran returns, the kingdom is broken just like him; and all the things that once made him useless to the militaristic culture of Westeros, now make him the ideal Fisher King: an incorruptible figurehead to help usher the new system. And thus Bran the Broken is immortalized as the story around which the kingdoms of Westeros can unite.

That passage appears in ‘The power of stories’, a video linked by me recently. Here is another passage from another fan:

GRRM’s answer to the question ‘How can mortal men be perfect kings?’ is evident in Bran’s narrative: Only by becoming something not completely human at all, to have godly and immortal things, such as the Weirwood, fused into your being, and hence to become more or less than completely human, depending on your perspective. This is the only type of monarchy GRRM gives legitimacy, the kind where the king suffers on his journey and is almost dehumanized for the sake of his people.

Tom Goodrich’s tragic journey into inner space certainly taught us to know outer space better than conventional WW2 historians, who, being unable to touch the Weirwood with the palm of their hands, never saw the past as it really happened.

Adolf quote

‘Hate is more lasting than dislike’.

—Hitler

Tom

Editor’s Note: With the exception of replacing the word ‘is’ for ‘was’ (and a few other words of that phrase changed from present tense to past tense), the following text was sent to me by Thomas Goodrich himself when a few years ago I asked him what he wanted me to put in the Metapedia article about him:

______ 卐 ______

Born and raised in the American Mid-west, Goodrich was a professional writer who lived in Florida. In addition to numerous books devoted to the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln, Goodrich has written several other highly popular works, including Scalp Dance—Indian Warfare on the High Plains, 1865-1879, Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate, and the ground-breaking book on World War Two, Hellstorm—The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944-1947.

Goodrich’s professional philosophy is simple:

My entire adult life has been devoted to the writing of unwritten history. As we all know, unless you learn from your history, you are doomed to repeat your history.

Thus, I have made it my life’s mission to give voice to history’s losers so that we might actually learn from our history, learn from both sides of our history, in the hope that we might thereby avoid repeating much of that history in the future.

From the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln to World War Two I have chosen the loser’s perspective in my books simply to find out what is mostly unknown and hence, find out what is almost entirely unwritten. Winners do indeed write history and the libraries are full of the winner’s accounts.

I write that one book, that one book which will hopefully help us to not only understand and learn from the “other side,” but will hopefully help us to understand and learn what real history is. Only by understanding both sides of history can we hope to avoid repeating that very history we would prefer to avoid.

As soon as I can afford it, I’ll order a copy of his book Scalp Dance.

Tom was what I’ve called a ‘three-eyed raven’ on this site, in the sense that he saw the historical past as only the greenseers in Martin’s fiction could. And that was because, like Bran the Broken, Tom was abused as a child.

Only those who are knocked off the tower by their parents or guardians and become disabled, but are survivors, are able to cross the Wall in search of the raven. And Tom was one of the very few greenseers in all of Westeros (in the TV series, only Bloodraven held the title of three-eyed crow, and when the old man died that title was inherited by Bran).

Adolf quote

‘He alone, who owns the youth, gains the future’.

—Hitler

Tom Goodrich

(21 November 1947 – 4 December 2024)

Michael Thomas Goodrich (born Michael Thomas Schoenlein), the author of what I consider the most important book written in English this century, died on Wednesday.

Not long ago, I exchanged my last correspondence with him, telling him I wanted to promote his books on this site; today, his publisher confirmed that he had passed away (see this Thursday’s interview esp. from 1:50).

Even in the last book of my autobiography in Spanish, I leave the reader with the thankless task of reading Hellstorm since without that reading, my mental transformation—from liberal to conservative, from conservative to white nationalist, and from white nationalist to National Socialist—could not be understood.

Goodbye, Tom. There are no writers like you left in your country. May some English speakers at least pick up your torch….

A concerned reader

Three recent comments by a commenter motivate me to quote, in a single post, all his comments since last year, including recent ones:

Eradicating non-Aryan elements from the planet is a legitimate, sensible and practical strategy for continued existence for Aryankind. People captured by Neo-Christian morality condemn such actions as evil. But what greater evil is the complete extinction of Aryankind and degeneration into an Untermenschen cesspool.

—posted last year in the thread ‘Black Bread’.

In any given future Aryan Ethno-state, societies or communities, Christian-related materials will be only be available to those who are extremely racially sound and immune to the Christian poison. Such materials are only to be used for historical or academic research or evaluation. Individuals who are able to access such materials should be as ruthless as Heinrich Himmler and fiercely racially loyal or unpolluted as SS members.

—posted in the thread ‘On John Milton’.

In Adolf Hitler: The Ultimate Avatar by Miguel Serrano, (Miguel Serrano was one of Savitri Devi’s companions and compatriots), it reveals that Yahweh and its supposed son Jesus are the demiurge. Yahweh is the evil “god” of the world and it is demonic. Whether this hypothesis is true or not, Aryans are the true stepping stone for the next stage in human evolution. As time and the Kali Yuga advances, the forces of decay and disintegration at work as described by Savitri will accelerate their actions against the true divine spark and chosen race of humanity which is the Aryan. The ultimate endgame is the devolution of humanity back to the ape and Neanderthals.

—posted in the thread ‘Moloch = Yahweh’.

Yes, the Serpent, Molech, Baal, Satan and Yahweh are one and the same, this is true of all Semitic entities. Yahweh symbolizes the entirety of the forces of decay in our present age that bring Aryans to their final doom, it is the prime mover of the Kali Yuga. The day of salvation will finally arrive for the Aryan once Christian ethics are extirpated from the world forever. I am shocked that there are no rigorous and supportive reactions from Aryans to this post. [emphasis added by Ed.]

—posted in Ibid.

I just hope the seed planted will blossom into an even mightier tree than the poisonous weeds that are Christianity and Neo-Christianity. Racially healthy Aryans in any future Aryan civilization or society will look back on Christians and Christianity as abhorrent and ridiculous as dunking your face or body into a pool of pig swill. If all Aryans in the entire world start burning bibles in bonfires and smashing the last stones of these very last churches into the ground, we knew that we had finally won.

—posted in the thread ‘Crusade’.

The near perfect comtemporary antithesis of the Christian poison are Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and members of the SS. The relentless and pathetic slander on Heinrich Himmler and the SS shows how afraid the racial enemies of the Aryan man are. It shows us a glimpse when Christian “values” and “ethics” (I would call that poison) are completely repudiated. Once the Christian poison is totally expunged from the soul of Aryan man, he is completely healthy again and it will be gameover for racial enemies, traitors and the world we known today.

—posted in the thread ‘Might is Right, 8’.

This is the precise reason it requires a systemic collapse of such unprecedented severity to weed out unworthy Aryans that are still entrapped in the snare of Christian ethics. The present status quo and the “world” as we knew it not only reinforce Christian ethics, it rewards and incentivizes them. The entire ludicrous and ridiculous notion of “last shall be first, the first shall be the last” will be proven false and illusory once the iron law of racial survival is the only way.

—posted today in the thread ‘Christian nationalism’.

I would like to say that the Christian “god”, which is a virulent mental virus [emphasis added by Ed.], is solely responsible for the population explosion of the racially and genetically inferior in the past few hundred years. It paves the way for Aryan extinction and it requires Kalki or an exterminationist solution to remedy it.

—posted in Ibid.

You might have a better chance of convincing a clumsy bull to climb or fly up a high wall than convincing Christian nationalists the error of their ways.

A racially-sound Aryan child or youth raised in a racially-healthy Aryan collective can easily understand the obvious contradiction of trying to preserve the biological existence of the entire Aryan collective and embracing a foreign Semitic god created from the foul sands of Judea.

Useless to state it again, many Christian nationalists are suffering from psychotic and schizophrenic ambiguity.

—posted in Ibid.

Adolf quote

‘The day of individual happiness has passed.’

—Hitler

by Gaedhal

I was reading Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy (1946). According to Russel, theism died out amongst the best minds in Europe, by 1700. This is, incidentally, how we could have a secular government established in America in the 18th Century. Aron Ra put a recording of Madeline Murray O’ Hare where she claimed that all the founders of America were atheists. In my view, this is an exaggeration. However, a lot of them weren’t theists. Thomas Jefferson called himself a materialist, as did Abraham Lincoln, four score and seven years later. John Adams wondered whether God even existed at all… which qualifies him as an agnostic. If only rich land-owning white men can vote—and, remember, white aristocrats have been having outbreaks of atheism since the Ionic Enlightenment, about 500 years before the common era—then the form of government that they would chose for themselves would be a secular godless government, in no way founded upon the Christian Religion, where Religion is only referred to as a negative phenomenon that must not be imposed, by the State, upon its citizens.

The reason why I am an elitist, of sorts, is because the mob is more than 300 years behind the intellectual elite in abandoning theism. Thankfully, some countries, like the United Kingdom, are transitioning into a post-theistic age.

The Philosopher Kings who established the United States, were non-theists. There might have been some sort of Aristotelian prime mover, who got the Cosmos started, however, this God no longer tinkers with or prods his creation. Thomas Paine, although a believer in an Almighty, of some deistic sort, nevertheless categorically rules out miracles. Paine thinks it absurd that a God would fix the laws of nature… and then break these laws through performing miracles. Paine does offer some positive arguments for God, such as the argument for God through mathematics/geometry/platonic forms… however, a god who doesn’t do miracles might as well not exist.

God used to have a lot of jobs to do. Prior to Newton and Galileo, objects were said to “prefer” to be at rest. Thus God’s might was needed to push the planets about the sky. If the planets are motoring across the sky, then God must be pushing them about. However Galileo and Newton proved that objects were utterly indifferent as to their being in motion or at rest. Thus, God was no longer needed to push the planets about the sky.

The motto of the Royal Society, headed up by Newton was and is: verba in nullius, which is Latin for: “We take nobody’s word for it”. In Christianity, we believe things because a holy-man said it. This is why Saint Paul is always vaunting how holy he is… how many times he went to prison for god… how poor and hungry he is for god. How many times he got flogged by the enemies of the Christian God. The holier one was, the more trustworthy he was meant to be.

Verba in Nullius is thus an antichrist saying. Scientists don’t give a fuck how holy you are. You either demonstrate what you claim, or it is not established. The Royal Society, thus, does not really care what God says, what Jesus says, what a Pope says, what a Holy Book says… Science is only interested in demonstrable reality.

However, another job that God had was to animate living things. Living objects, thanks to a false idea inherited from Aristotle, were also said to prefer rest. The fact that living things existed at all was proof—yes proof!—that God exists. However, the Biochemistry of which living things is composed is also totally indifferent—it has no preferences—whether it be at rest or in motion. Thus, there is no need for a god to animate our bodies through a magical object called a ‘soul’—or, in Latin: ‘anima’. Thus, there is no longer any need for a Great Cartoonist in the Sky to animate Aristotelian rest-preferring biological bodies with souls.

Hell was also disbelieved in by 1700, according to Russell. Newton was a Unitarian, and so, by rights, he should be shrieking up his bloody lungs in fiery torment, in Yahweh’s superheated torture chamber. However, the idea that Newton was in Hell was too much to swallow.

To recap: the elitists who founded America had all of this sussed out by the founding. They were deists, agnostics, materialists etc.

However, 300 years later, amongst the American mob, the Christian Superstition, is still rife among the populace. America is in real danger of succumbing to Christian Nationalism.

The mob will eventually abandon theism in America, though, just as they have already done in the United Kingdom… however, the mob always seems to be centuries behind the intellectual elite.

To me, the chapter: ‘The Rise of Science’ really demonstrates the gulf that exists between the elite philosophers, and the superstitious mobmen.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s 2 ¢

In certain quarters of the American racial right, Christian nationalism is popular.

For someone who, like me, already admired pantheism since 1973 and 1974 when we were taught Hegel at school, and knew about the existence of the pantheist theologian Teilhard de Chardin, I am surprised by the atavisms that Americans still suffer from. If only the racialists would take Uncle Adolf’s after-dinner talks as their guidebook! But even before Hitler, philosophical-theological treatises had already been published in Germany, which distanced the readers from the theism that persists in the hemisphere where I live.

For someone who, like me, already admired pantheism since 1973 and 1974 when we were taught Hegel at school, and knew about the existence of the pantheist theologian Teilhard de Chardin, I am surprised by the atavisms that Americans still suffer from. If only the racialists would take Uncle Adolf’s after-dinner talks as their guidebook! But even before Hitler, philosophical-theological treatises had already been published in Germany, which distanced the readers from the theism that persists in the hemisphere where I live.

It is not surprising that Karlheinz Deschner’s work on Christian criminal history has been translated and published in Spanish but not published in English. And with such gross ignorance do the racialists pretend to lead their country forward?

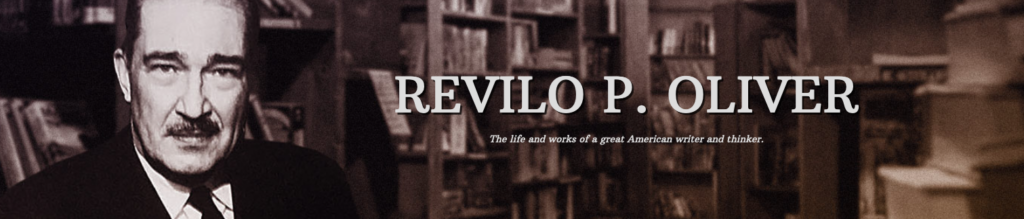

Oliver’s essay

The PDF of Revilo Oliver’s article

on Christianity is now available here.