against the Cross, 4

Nietzsche had to argue with his mother over his resolution not to continue his theological studies, i.e., to prepare for the career of parish priest.

Nietzsche had to argue with his mother over his resolution not to continue his theological studies, i.e., to prepare for the career of parish priest.

In Bonn, Nietzsche finally experienced his first breaths of freedom. He no longer had to comply with the rigorous rules of dress, or the obligation to attend religious services in what had been, de facto, the Schulpforta convent for kids. Moreover, Bonn was so far from his mother’s home that he couldn’t even afford to spend Christmas at home. The difference between Bonn and the sullen family life in Naumburg couldn’t have been greater for the young student who attended parties, something inconceivable in Schulpforta.

Nietzsche, who came to live very close to Beethoven’s birthplace, visited Schumann’s grave. His friend Paul Deussen, who was the same age (but who would outlive him by almost twenty years) told the anecdote that Nietzsche didn’t accept the services of prostitutes when they took him to a brothel during one of his escapades in Cologne. More than adolescent sex, music was his girlfriend. As the teenage Hitler would later do, he attended concerts and the opera despite their financial hardship.

A letter to Deussen opens a psychological window into how the young Nietzsche first discovered the late atavistic effects of pagan festivities:

The entire population of the city lived for three days in total debauchery… There was complete freedom to visit and to receive visitors, even to kiss. Breakfast was ready in every home, accompanied by wine and punch; joking and laughing, drinking a glass, and then the round went on… When they arrived at the house of a slaughterer, the party had passed through the window, which was easy, since in the Rhineland houses have very low windows… The students kissed the splendid girl leaning out of the window and left through the front door. In the meantime, the father objected to the custom of wearing masks and wanted to prevent the parade. That’s why I was called. I carried the rather stout man outside and closed the entrance, then collected up my kiss and the procession moved on.

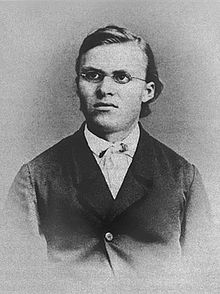

It was a time when the young Nietzsche already wore a moustache, though by no means the bristling wig with which, after his death, his face became iconic. He was such a gregarious young man that in addition to the opera he attended the theatre with friends. No one could have suspected that he would eventually become a hermit. So little noticed was the normie Nietzsche among lads of his age that, except Deussen, no member of the ‘Franconia’ association to which he belonged remembered anything about him when he was already famous. Nietzsche’s German biographers swim in information and documents about his life, to the extent that even some of his class notebooks have come into the public light for centuries to come.

If, to his mother’s chagrin, Nietzsche had abandoned his theological studies after one semester and started studying classical philology with Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl, the following year, in October 1865, following his teacher Ritschl, he went to the University of Leipzig. Nietzsche’s experiences in Leipzig are recounted in a colourful account, Retrospect of My Two Years in Leipzig. When he enrolled in the faculty of philosophy at the University of Leipzig, a century had already passed since Goethe had done so.

With his mentor Ritschl Nietzsche again showed himself industrious: a model student as he had been at Pforta. Ritschl gave his favourite pupil heavy assignments, such as extracting and collating ancient texts and indexing the issues of the Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. In 1866 Nietzsche gave his first lecture at the Philological Association and befriended the student Erwin Rohde, who was to become his best friend. This was the time of the war between Prussia and Austria, in which Prussia emerged victorious although Nietzsche, a Prussian in Leipzig, objected to the city becoming immediately Prussian. But the young scholar writes about that year: ‘I often longed to be torn away from my monotonous labours’.

On 9 October 1867, Nietzsche began his military service with a cavalry regiment. These were terrible times on the other side of the Atlantic, when the Mexican Indian Benito Juárez had Emperor Maximilian shot in Mexico. (In sharp contrast to today’s traitorous white Mexicans who admire Juárez, my great-great-grandfather José María Tort y Vivó, a Catalan living in Mexico mentioned by José Zorrilla in Recuerdo del Tiempo Viejo, was a staunch supporter of Maximilian of Habsburg.)

In March 1868 Nietzsche suffered a fall from a horse, but the period of convalescence served as an opportunity to approach philosophy and in October he finished his military service. Once again: terrible things were happening on the other side of the Atlantic. Blacks were granted the right to vote in the United States because of the triumphant Christian ethics of the Yankee Puritans (at a time when Jewry hadn’t yet taken over the media). But by then the twenty-three-year-old young man already bears the name of Nietzsche.