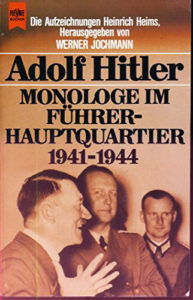

A detailed discussion of the content of Hitler’s monologues can be dispensed with in this context given the extensive recent Hitler research. However, even in the context of a brief sketch, references to facts that belong to the secured state of knowledge cannot be avoided.

First and foremost, Hitler bears witness to himself in his discussions, especially during the long evening and night hours when he spoke his thoughts ‘into the impure’. The man who was at the zenith of his power, who dominated large parts of Europe and directed the deployment of his armies in Russia, who could look back on a series of steady successes lasting more than ten years until the crisis of the winter of 1941/42, undoubtedly possessed high intellectual abilities. With his present knowledge in the field of military affairs, armament and technology, he always made a strong impression on those around him. This was no less true for problems of art and especially history and politics. On the other hand, he showed much less interest, as a long-standing confidant confesses, in questions of the ‘humanistic field of knowledge’.[1] Thanks to his extraordinary memory and remarkable knowledge of literature, Hitler achieved insights and findings in specialised fields that commanded the respect of many experts. He was usually superior to them in his ability to grasp the core of a problem immediately and to reduce complicated relationships to a simple denominator. Above all, Hitler not only knew but, according to the testimony of Grand Admiral Raeder, ‘formed views and judgements from it that were often remarkable’.[2] He was able to think in large contexts and was in many respects far ahead of his advisers, for example on the question of motorizing the German army.[3]

Hitler’s monologues at his headquarters bear witness to these abilities only to a limited extent. Examples are his terse remarks on questions of environmental protection, the warning against the consequences of unrestrained exhaustion of the earth’s reserves of raw materials (Monologue 1), the demand for better utilisation of the countries’ natural resources (15, 16), or even the realisation, by no means common at the time, that the automobile would overcome borders and link peoples together more strongly than before.

For Hitler, motorisation was an important step ‘on the way to a new Europe’ (2). The correctness of these and other insights are not affected by the fact that he hindered this development through his policies. Knowledge, worldview and political practice collided.

The extent to which the ‘Führer and Reich Chancellor’ was aware of this tension will not be clear. Even during his monologues at the Führer’s headquarters, he never forgot the necessary restraint regarding his intentions and plans. Even in the smallest of circles he did not betray any secrets, did not reveal doubts or uncertainty. At no time did he weigh up the pros and cons with his advisors before making major decisions, nor did he make it clear what the motives were for his actions in concrete political and military situations.

Heim’s notes testify to Hitler’s great self-control, but also his suspicious reserve. The guests at the table were given no indication of the information coming from Germany and abroad, how the German people reacted to the sacrifices and deprivations, and what repercussions the severe crisis of the winter of 1941/42 had on the population of the occupied territories and the allied states. In general, Hitler’s thoughts were far more on the past or the future than the present. With great willpower, he repressed the problems and worries of everyday life at the dinner table and acted as an attentive host, casually talking about Bruckner and Brahms or appropriate nutrition or reporting on events or figures from the early days of the NSDAP.

In this behaviour, however, another trait of Hitler’s becomes visible. He was not a political pragmatist who concentrated on solving the issues of the day, but the representative of a world view that he wanted to help to achieve victory. That is why he looked to the future, especially in times when a lot was coming at him. Convinced that he knew the ‘eternal law of nature’ (117) and that his mission was to help it come to fruition, he made great efforts to free himself from burdens and difficulties, to defy resistance and often even facts that did not fit into his concept. He knew very well the limits imposed on human action, but believed that through energy, especially through an unshakeable and uncompromising belief in his mission, he could push them far out and force people as well as powers under his spell.

Hitler was convinced that the epoch of the bourgeoisie was over and that the bourgeois nation-states would not survive the war. In his opinion, in the world war of the present day, they would inevitably disintegrate—since they lacked inner strength and a unifying force—and the vital and unconsumed layers of the nations would then strengthen the camp that fought with particular determination and faith. Just as National Socialism had prevailed in the internal political struggle against far superior forces of the parties and the means of the power of the state, so it had to assert itself in the war with the utmost determination and readiness to believe. Not the superior weapons, but the more devout fighters would ultimately bring about the decision.

On 27 January 1944, Hitler very clearly and firmly told the field marshals and commanders that it was precisely this devout readiness of each soldier that mattered. ‘It is completely unknown to many’, he declared, ‘how far this fanaticism goes, which in the past moved so many of my party comrades to leave everything behind them, to allow themselves to be locked up in prisons, to give up a profession and everything for a conviction… Such a thing has only happened in German history in the time of the religious wars, when hundreds of thousands of people left their homes, farm and everything and went far away, poor as church mice, although they had previously been wealthy people—out of a realisation, a holy conviction. That is the case again today’.[4]

There is no doubt that the National Socialists had an advantage over the bourgeois parties of the Weimar Republic because of their readiness to believe and devote themselves. And Hitler certainly helped his party overcome defeats and serious crises by never giving up, showing confidence especially in difficult situations and thus lifting his followers. Part of his strength lay in this steadfastness and belief in his mission (32). In the same way, Hitler also tried to convey to the German people during the war the feeling of superiority and the conviction of final victory. This undoubtedly succeeded to a great extent, as long as the expectations did not contradict the realities. In the long run, however, willpower and strength of faith were not enough to withstand the growing pressure of the war opponents. Among the concrete power factors on the opposite side that became more and more apparent was the internal stability of the Soviet Union, the efficiency of the Red Army and the economic strength of the country, the unity and willingness to resist of the British population, the industrial potential of the USA, the will of the nations of Europe conquered by Germany to live and to be free.

______ 卐 ______

Note of the Editor: Free? Western nations today are slaves of an ethno-suicidal religion spawned by the Allies right after WW2!

______ 卐 ______

It cannot be assumed that Hitler failed to recognise these realities, as his statements in the Führer’s headquarters would lead one to believe. Even in the conversations in his inner circle, he did not lose sight of the psychological effect of his words. Remarks such as that the Americans are ‘the dumbest people imaginable’ (82), assertions about England’s growing difficulties (81, 88) or Germany’s perpetual superiority in weapons technology (84) were intended first and foremost to strengthen the self-confidence of those around him. He felt it necessary to counteract the sober assessments of the situation by his political advisers, who, in his opinion, inhibited the momentum of the soldiers and the population through their restraint and caution. Hitler was convinced that he had only achieved so much thanks to his ‘mountain-moving optimism’ (79).

More fundamental importance is attached to the statements on questions of domestic policy and worldview. The leader of the Third Reich was a bitter enemy of the revolution with its egalitarian and democratic driving forces. In his opinion, it was destructive and its bearers belonged to the negative selection of the people. Again and again one finds the assertion that the judiciary had nurtured criminality during the First World War, that in 1918 it was only necessary to open the prisons and already the revolution had its leaders (18, 52, 60). In other contexts, however, the achievements of the revolution are praised. It did away with the princes (20), broke up the class state, challenged the monopoly of the educated and propertied bourgeoisie and thus opened up opportunities for advancement to empower people from the lower classes (26, 50, 56). Sometimes even credit is given to the revolutionaries. Given the ‘stupid narrow-mindedness’ of the Saxon bourgeoisie, for example, the influx of workers to the KPD in that country was very understandable (13), just as communists like Ernst Thälmann generally elicited much more sympathy from him than aristocrats like the Austrian Prince Starhemberg (13), who had even taken part in the 1923 putsch in Munich in his entourage.

In all this, however, Hitler left no doubt in his discussions about how closely he felt bound to the nation-state tradition of the 19th and early 20th centuries and intended to complete what had been developed and propagated before him in the way of large-scale concepts and imperial ideas. However, he was convinced that he would only achieve this goal if he could rely on a broader, more powerful and more vital support class. The bourgeoisie and the old ruling classes seemed unsuitable for this. In unusually harsh terms, he criticised the former German ruling houses as well as the ruling princes of Europe (9, 20, 55), the nobility, the officer corps (13,28,31), the diplomats (121), civil servants and lawyers (14,48,130), the intellectuals and scientists. Again and again, the bourgeoisie in toto is accused of half-heartedness, cowardice and incompetence (13,20). The capitalist system is not spared either (15). ‘The economy’, Hitler declared bluntly, ‘consists everywhere of the same scoundrels, ice-cold money-earners. The economy only knows idealism when it comes to workers’ wages’ (39).

Well-known representatives of German industry and some bourgeois experts who heard such and even harsher statements by Hitler considered him a radical zealot or even a Bolshevik in disguise.[5] This view, however, does not get to the heart of the problem any more than the opposite view, which wants to conclude from words of appreciation for entrepreneurs and praise for the efficiency of the German economy and its promotion that Hitler was dependent on these circles. In these monologues there is no evidence that Hitler wanted to serve the interests of capital. He did not bind himself to any class, he hardly took into account the interests of certain groups and strata. In the National Socialist state, classes were to be eliminated and thus all the forces of the people were to be set free, and all sections of the population were to be given opportunities for advancement and activity. All groups were to be united in the Volksgemeinschaft, the national community a new higher unit.

However, since in the National Socialist Volksgemeinschaft the rights and functions of the social groups were not finally defined, nor were the NSDAP and its branches assigned any clearly defined tasks, it functioned as long as everyone derived advantage from it and saw part of their interests and demands realised. As the demands grew, there were signs of fatigue, resignation and communal refusals. Hitler increasingly found himself criticising state organs (107), civil servants (41, 59), judges (130, 177), party leaders and ministers for being too lenient towards individual and group interests. However, as long as there was still a basic consensus among the majority regarding the goals for which they were fighting, the state and party leader imposed his will unchallenged in all decisive questions.

That this succeeded so unreservedly was undoubtedly due to the dynamism that the leader of the NSDAP had unleashed in Germany. He did this based on the realisation that in times of social upheaval, economic and political change, authorities and institutions reacted too slowly and sluggishly, that experts in all fields had insufficient answers and solutions to offer, and that as a result of the confidence in the state and its organs was severely shaken. If unconventional methods were practised in such situations, if alternatives were developed with unused forces, then these would receive an advance of confidence from the outset. Hitler built on this. Through the establishment of special offices, the granting of special powers and special orders, the National Socialist regime gained a remarkable momentum, initially even a momentum that lasted in some areas into the first years of the war.

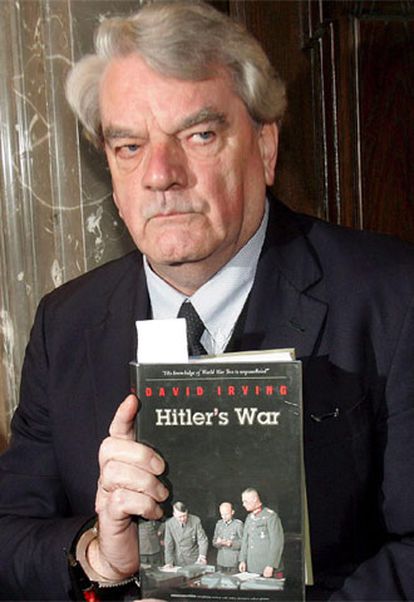

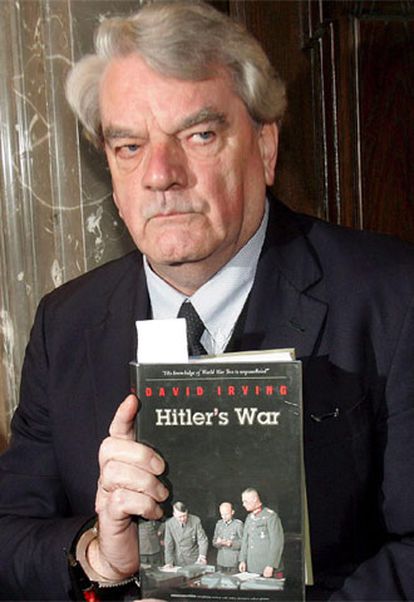

However, this process also caused considerable difficulties. A seemingly endless chain of competence disputes and rivalries developed, leading to friction, disorganisation and, in many cases, failure. Hitler, to secure the support of all forces for the speedy implementation of his plans, triggered this dynamic and held on to the system even when the disadvantages became openly apparent. David Irving concludes, therefore, that he was far from being the all-powerful leader and that his influence over those directly under him diminished, especially under the extreme stresses of war.[6] This thesis is correct insofar as Hitler’s will did not always and in all areas penetrate to the lowest state and party organs, and was also interpreted and understood differently due to a lack of ideological unity in the party. In the monologues presented here, he complains about the failure of the SA leaders (79), the high-handedness of individual Gauleiters, and the inadequate implementation of his orders. But it is wrong for Irving to conclude that the conduct of the war so absorbed Hitler’s strength and concentration that he left the areas of domestic and occupation policy to his responsible ministers and confidants, especially Himmler, Goebbels and Bormann. The reader of these monologues can convince himself of the opposite.

However, this process also caused considerable difficulties. A seemingly endless chain of competence disputes and rivalries developed, leading to friction, disorganisation and, in many cases, failure. Hitler, to secure the support of all forces for the speedy implementation of his plans, triggered this dynamic and held on to the system even when the disadvantages became openly apparent. David Irving concludes, therefore, that he was far from being the all-powerful leader and that his influence over those directly under him diminished, especially under the extreme stresses of war.[6] This thesis is correct insofar as Hitler’s will did not always and in all areas penetrate to the lowest state and party organs, and was also interpreted and understood differently due to a lack of ideological unity in the party. In the monologues presented here, he complains about the failure of the SA leaders (79), the high-handedness of individual Gauleiters, and the inadequate implementation of his orders. But it is wrong for Irving to conclude that the conduct of the war so absorbed Hitler’s strength and concentration that he left the areas of domestic and occupation policy to his responsible ministers and confidants, especially Himmler, Goebbels and Bormann. The reader of these monologues can convince himself of the opposite.

Without him, the Führer and Reich Chancellor believed, Germany could pack up (79), and important decisions had not been made (32). Hitler was also convinced of his indispensability at his headquarters; he was excellently informed and did not fail to intervene wherever he thought it necessary. He criticised clumsy formulations in an editorial by Reich Minister Goebbels, registered events in individual districts, paid attention to the promotion of the arts, forbade attempts at administrative simplification in the war, ordered the shooting of the arsonist of the ‘Bremen’, supervised and reprimanded the judgements of German courts, took note with indignation of the sermons of the Bishop of Münster. As the minutes of the Speer Ministry meetings and many other testimonies show, Hitler allowed himself to be informed down to the last detail and made his own decisions, especially in domestic matters. No one knew better than he that the war could only be fought if a majority of the people followed it, or at least accepted the inevitable. For this very reason, he devoted extraordinary attention to the tasks of domestic policy, especially domestic security.

Even more important is another consideration. Hitler waged the war because it was the consequence of his worldview: the living space of the German people was to be conquered and secured for many generations. He spoke about this very forcefully again and again in his headquarters. Only this gain of land would create the prerequisite for solving the social question. By offering each individual the opportunity to fully develop his abilities, the National Socialist programmer hoped to reduce or eliminate the tensions and rivalries in the community (140). In this war of worldviews, Hitler did not lose sight of the goals for which he was waging it. The most important was the consolidation of National Socialist supremacy in Europe and the expansion of German influence in the world. General questions of occupation policy in East and West, as well as cooperation with allied states and peoples, belonged in this context. In Hitler’s view, German rule could only be secured if it succeeded in winning over as many people of ‘Germanic blood’ in the world as possible (125). The prerequisite for strengthening one’s nationality, however, was the repression and elimination of all those who were considered inferior and alien to the community: Jews, Slavs, Gypsies and others. Finally, it was a question of suppressing the influence of those circles that did not recognise war as the ‘law of life of peoples’, that did not want to accept the ‘right of the strongest’ in social coexistence, nor race and descent as criteria in professional competition: Christians, Marxists, pacifists. In these areas Hitler never delegated responsibility, but reserved every fundamental decision for himself. Irving’s assertion that Hitler was not informed about essential measures precisely in this area, which was central to him, cannot be substantiated. An analysis of the monologues points’ in the opposite direction.

_____________

[1] Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler, wie ich ihn sah. Munich-Berlin 1974, p. 160 f.

[2] Erich Raeder, Mein Leben. Vol. 2, Tübingen 1957, p. 110.

[3] Fritz Wiedemann, Der Mann, der Feldherr werden wollte. Velbert and Kettwig 1964, p. 102.

[4] Excerpts from this speech can be found in the appendix to the collection of Bormann’s Führer Talks.

[5] Walter Rohland – Bewegte Zeiten. Erinnerungen eines Eisenhüttenfachmanns (Memories of an Ironworks Expert). Stuttgart 1978, p. 82 reports on a statement of displeasure by Hitler during a meeting. Afterwards he had declared, ‘If only I had destroyed the entire intelligentsia of our people like Stalin, then everything would have been easier!’

[6] David Irving,. London 1977, p. XV.