There is no shortage of opponents of Marxism. They range from those who condemn all violence and are frightened by the known episodes of ‘class struggle’ in Russia and China, to those who reproach the Communists for their atheism and materialism, to those who own some property and are afraid of losing it if they have to live under the sign of the Sickle and Hammer.

Many oppose it in the name of some political doctrine, usually embodied in a ‘party’, which, if it attacks the ‘subversive’ character of Marxism, is itself no less subversive, and for the same deep reasons. This is the case with the adherents of all democratic parties, whose common denominator is to be found in the belief in the ‘equality in law’ of all men, and hence the principle of universal suffrage, of power emanating from the majority. These people don’t realise that Communism is in its infancy in this very principle, as it was already in Christian anthropocentrism (even if it is a question of the value of human souls in the eyes of a personal God who infinitely loves all men). They don’t realise that it is and can only be so, for the reason that the majority will always be the mass—and increasingly so, in an overpopulated world.

Only those who are faithful to any adequate expression of immemorial Tradition, and in particular to any true religion or to any Weltanschauung capable of serving as a basis for a true religion—any worldview which is ultimately based on the knowledge of the eternal and on the will to make it the principle of the socio-political order—, are fundamentally opposed to Marxism.

Now, disregarding the apparent paradox of such an assertion, twenty-five years after the collapse of the Third German Reich I dare to repeat that the only properly Western doctrine which (after the very old Nordic religions which Christianity persecuted and gradually killed between the 6th and 12th centuries) fulfils this condition is Hitlerism.

______ 卐 ______

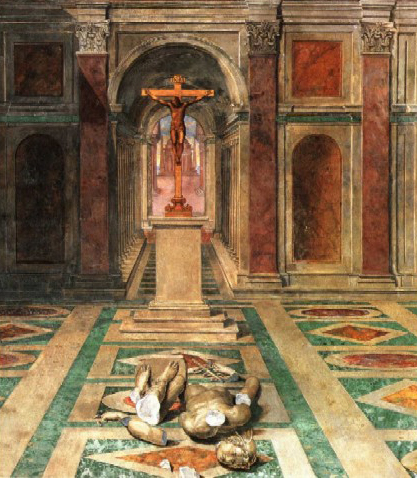

Note of the Editor: Once more, Savitri didn’t know about the apocalypse of whites that also represented, in the 4th and 5th centuries, the violent destruction of the classical world by fanatic Christians. We cannot blame her. Books like this one had not been published! More recently than Savitri’s time, even Mauricio didn’t know about the blackest page of ancient history, as he commented yesterday.

Note of the Editor: Once more, Savitri didn’t know about the apocalypse of whites that also represented, in the 4th and 5th centuries, the violent destruction of the classical world by fanatic Christians. We cannot blame her. Books like this one had not been published! More recently than Savitri’s time, even Mauricio didn’t know about the blackest page of ancient history, as he commented yesterday.

______ 卐 ______

This is the only Weltanschauung infinitely more than ‘political’ that is clearly ‘against Time’ in accordance with the eternal. It is the only worldview which, in the long run, will triumph both over Marxism and the general chaos to which it will have led the world—and this, no matter how great the material defeat of its followers may have been yesterday, and no matter how hostile millions of men may be about it today. Only a total recovery can succeed a total subversion: a glorious beginning of the cycle at a lamentable end of it.

But our opponents won’t fail to draw everyone’s attention to the eminently ‘anti-traditional’ character of more than one aspect of National Socialism, both during the Kampfzeit, before 1933, and after the seizure of power. If it is ‘subversive’ from the viewpoint of eternal values to preach the ‘class struggle’ with a view to the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. But wasn’t it equally subversive to rise to power democratically thanks to universal suffrage, by relying on a succession of electoral campaigns (on the protection of young fighters, for the most part as ‘proletarian’ in their behaviour, as the Communists whose attacks they repelled during meetings and whom they overcame in street battles)? Wasn’t it to be so, to keep this power, which came from the people—the masses—and to omit the reestablishment of the old monarchy despite the last and fervent recommendation of Marshal von Hindenburg, President of the Reich?

On the other hand, didn’t several German banks[1] as well as industrial magnates[2] subsidised the NSDAP, thus making the success of the National Socialist Revolution depend, in part, on the power of money and running the risk of making it considered, despite its popular appearance, the supreme defence of the ‘capitalist’ order as it already existed—that is to say, a society extremely distant from the traditional ideal?

Finally, it may be said, how can it be denied that, even after the seizure of power the Third German Reich was far from presenting the appearance of an organism inspired from top to bottom by the vision of the cosmic hierarchy? The famous author Hans Günther himself, apparently disillusioned, wrote to me in 1970 that he had, unfortunately, seen in it ‘an ochlocracy’ rather than the aristocratic regime he had dreamed of. And one cannot categorically reject without discussion this judgement of one of the most prominent theorists of Hitler’s racism before the disaster of 1945. The judgement, while undoubtedly excessive, must, in more than one particular case, certainly express some regrettable reality.

Let’s never forget that we are approaching the end of a cycle, and that the best institutions can therefore only exceptionally have a semblance of the perfection of the past. For everywhere, and the post-war period has amply proved this, there are more and more two-legged mammals and fewer and fewer men in the strongest sense of the word. No doctrine should therefore be judged by what has been accomplished in the visible world in its name.

The doctrine is true or false depending on whether or not it is in unison with that direct knowledge of the universal and eternal which only a steadily diminishing minority of sages possesses. It is true—it cannot be repeated often enough—regardless of the victory or defeat of its followers, or so-called followers on the material plane, and regardless of their weaknesses, foolishness, or even crimes. Neither the atrocities of the Holy Inquisition, nor the scandals attached to the name of Pope Alexander VI Borgia, take anything away from the truth of the vision of the ‘intelligible world’ that a Master Eckhart, for example, or some initiated Templar, may have had through Christian symbolism. And the same is true of all doctrines.

We must therefore be careful not to impute to Hitlerism the faults, weaknesses or excesses of people with power, to any degree whatsoever, under the Third Reich or during the period of struggle (Kampfzeit) from 1920 to 1933, and especially the faults or excesses committed against the spirit of the Weltanschauung and the Führer’s dream, as there seemed to be so many. In German society, as it was under the growing influence and effective rule of the Führer during the Kampfzeit and afterwards, we must see only the Führer’s efforts to mould it according to his dream, or to prevent it from evolving against that same dream. We must try to understand what he wanted to do.

Already in the official National Socialist texts addressed to the general public—in the Twenty-five Points, which form the basis of the Party programme; and above all in Mein Kampf where the great philosophical directives of the latter are traced out even more clearly—it is visible that the Movement was directed against the most cherished ideals and the most characteristic customs of the eminently decadent society, which had grown out of the Liberalism of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Lending at interest, financial speculation, and any form of gain alien to a creative endeavour, as well as the exploitation of vice or silliness in a press, literature, cinema or theatre envisaged above all as a means of making a profit, are condemned with the utmost rigour. Moreover, the very principles of modern Western civilisation—the equality of all men and all races in law, the idea that ‘law’ is the expression of the will of the majority, and ‘nation’ the community of those who, whatever their origin, ‘want to live together’; the idea that perpetual peace in abundance, the fruit of man’s ‘victory over nature’ represents the supreme good—are attacked, ridiculed and demolished in a masterly manner.

Natural law, the law of the struggle for life, is recognised and exalted on the human level as on all other levels. And the primordial importance of race and personality—the two pillars of the new faith—is proclaimed on every page. Finally, this new faith, or rather this new conception of life (neue Audassung) for the Führer and the few, is not a question of ‘faith’ but true knowledge. It is characterised as ‘corresponding to the original meaning of things’[3] which says a lot, this ‘original meaning of things’ being none other than that which they take on in the light of Tradition.

We can therefore, without going any further, affirm that everything in the history of the National Socialist Party that doesn’t seem to coincide with the spirit of a struggle ‘against Time’ is a matter of the tactics of the struggle, not its nature or purpose. It was under the pressure of hard necessity, and only after he had failed on 9 November 1923 in his attempt to seize power by force that Adolf Hitler, released from his Landsberg prison but now deprived of all means of action, had recourse—reluctantly to be sure—to the slow and long ‘legal way’, that is to say, to the repeated appeal to the voters and the gradual conquest of a majority in the Reichstag. It is well known that his first move after taking power ‘by democratic means’ was to replace the authority of the many with that of one, namely his own at all levels; in other words, to abolish democracy: to bring the political order into line with the natural order as far as possible.

It was under the pressure of a no less compelling material necessity—that of meeting the enormous expenses involved in the struggle for power in a parliamentary system with its inevitable election campaigns—that he had to accept the help of the Hugenbergs, the Kirkdorfs, the Thyssens, Dr Schacht and later Krupp, as well as of a host of industrialists and bankers.

Without it, he couldn’t have risen to power fast enough to block the road to the most dangerous forces of subversion: the Communists. For money is, more than ever, in a world which it increasingly dominates, the ‘sinews of war’ and politics. Does this mean that the Führer was subservient to money or to those who had given him money during the Kampfzeit? Does it mean that he made any concessions to them after taking power?

Far from it! He allowed them to get rich insofar as, in so doing, they served the national economy effectively and gave the working masses what he had promised them: abundance through work insofar as, subject to his authority, they continued to help the Party, i.e. the state, in peace and war. He kept them in their place and their role—like a king and the merchant ‘caste’ in a traditional society—thus showing both his realism and wisdom.

On the other hand, the (at least partial) ‘ochlocracy’ that has so often been attributed to National Socialism was, in fact, only the inevitable corollary of Adolf Hitler’s obligation to come to power by relying, quite democratically, on the majority of the electorate. It wouldn’t have existed if the putsch of 9 November 1923 had succeeded and had given him free rein to remake Germany according to his immense dream. It wouldn’t have existed because he wouldn’t have needed the collaboration of hundreds of thousands of young people ready to do anything: to strike blows as well as to receive them, to maintain in the vicinity of his massive propaganda meetings, and in the halls themselves, an order constantly threatened by the physical attacks of the most violent and implacable elements of the Communist opposition.

To conquer Germany ‘democratically’ he had to show himself, to be heard, hundreds and hundreds of times to convey to the public his message: part of his message, at least that which would induce the masses to vote for his party. The message was irresistible but it had to be communicated. And that would have been impossible without the wolf pack, the SA[4], who ruled the streets and who, at the risk of their own lives, ensured the Führer’s silence and safety amid his audience.

Adolf Hitler loved his young beasts, madly attached to his person, eager for both violence and adoration, many of whom were former Communists who had been won over to the holy cause by the fascination of his words, his looks, his behaviour and his doctrine in which the son of a proletarian saw something more outrageous, more brutal, and therefore more exalting than Marxism.

He loved them. And he loved the latest of their supreme leaders of the Kampfzeit, under whose orders he himself had once fought in the war: Ernst Röhm, who had returned from Bolivia, from the end of the world, at his call in 1930. He willingly turned a blind eye to his deplorable morals and saw in him only the perfect soldier and genius organiser.

And yet… he resigned himself, despite everything, to having this old comrade killed, or to let him be killed—almost the only man in his entourage who was on a first-name basis with him[5]—as soon as he was convinced that the turbulence of this troop, so faithful though it was, its spirit of independence and especially the growing opposition which was emerging between it and the regular German army could only lead precisely to ochlocracy, if not to civil war; in any case, only to the weakening of Germany.

One could compare this tragic but apparently necessary purge of June 30, 1934 with the most Machiavellian settlements of accounts in history; for example, the execution without trial of Don Ramiro di Lorqua on the orders of Caesar Borgia—with this crucial difference, however: that, while the Duke of Valentino had in mind only power for himself, the Führer aimed infinitely higher. He wanted power to try, in a desperate effort, to reverse the march of Time against itself, in the name of eternal values. There was nothing personal in his struggle at any stage.

And if, despite the fervent desire of Field Marshal and Reich President von Hindenburg, he rejected any idea of restoring the monarchy, it was not out of ambition either. It was because he was aware of the vanity of such a step in terms of values and true hierarchies. The monarchy ‘by divine right’, the only normal one from the traditional point of view[6] had, for centuries already, lost all meaning and justification in Europe.

The Führer knew this. It was not a question of trying to restore a shaky order by reinstalling a parliamentary monarchy presided over (there is no other word) by William II or one of his sons. He wanted to build a new order, or rather to resurrect the oldest order: the ‘original’ order in the strongest and most durable form it could take in this century.

And he knew that, by the choice of those forces of life which, throughout any cycle of time, untiringly oppose the ineluctable current of dissolution, he—the eternal Siegfried, both human and more than human—held both the legitimate power in this visible world and the legitimate authority emanating from beyond: the ‘power of the two Keys’. With him at the top, the pyramid of earthly hierarchies was to gradually resume its natural position, once again depicting in miniature, first in Germany, then throughout Europe and the Aryan world: the invisible Order which the Cosmos depicts in large.

It was in the name of this grandiose vision of ideal correspondences that he rejected, with equal vigour, Marxism: a doctrine of total subversion; Parliamentarism in all its forms, always based on the same superstition of quantity; and ochlocracy, a source of disorder, and therefore of constant instability.

But the traditional character of his wisdom is to be sought even more in the few texts that give us his secret, or at least intimate, talks, his open-hearted confidences in front of a few selected people, than in his writings or speeches addressed to the general public.

__________

[1] The Deutsche Bank, the Commerz und Privat Bank, the Dresdener Bank, the Deutsche Credit-Gesellschaft, etc.

[2] E. Kirkdorf, Fritz Thyssen, Voegler, Otto-Wolf von Schröder, then Krupp.

[3] ‘…unsere neue Auffassung, die ganz dem Ursinn der Dinge entspricht…’ (Mein Kampf, 1935 edition, page 440).

[4] Sturmabteilungen or Storm Troops.

[5] With some of his other early collaborators, such as Gregor Strasser.

[6] The elective kingship of the ancient Germans, that of the Frankish warrior raised to the flagstaff by his peers, was also ‘of divine right’ if we admit that the ‘divine’ is none other than the pure blood of a noble race.

Editor’s note: So far my insistence on pointing out Chris Martenson’s course (summary: here) has not made a dent in the racialists’ worldview. Savitri ignored scientific data on what now is called peak oil because neo-Malthusian studies weren’t yet popular. Never mind that Martenson and others who talk about energy devolution are normies. What matters is whether their calculations are correct. As I have also said several times, among the racialists only the Austrian-Canadian Ernest Ronin has predicted that when energy devolution hits the fan, later in this century, a window of opportunity will open for our cause.

Editor’s note: So far my insistence on pointing out Chris Martenson’s course (summary: here) has not made a dent in the racialists’ worldview. Savitri ignored scientific data on what now is called peak oil because neo-Malthusian studies weren’t yet popular. Never mind that Martenson and others who talk about energy devolution are normies. What matters is whether their calculations are correct. As I have also said several times, among the racialists only the Austrian-Canadian Ernest Ronin has predicted that when energy devolution hits the fan, later in this century, a window of opportunity will open for our cause.