Since I mentioned The Yearling in my previous post, I must say that at Chechar’s (here) I have just copied and pasted the ten entries originally posted here but in reverse order; that is, in a way that the reader doesn’t have to read them backwards but may start from chapter 1.

Category: Yearling (novel)

Further to what I said yesterday.

A deeper response to the questions raised by Stubbs would imply reminding my readers that, at the end of his Critique of Practical Reason, Kant said that there are two universes: the empirical universe and the subjective universe. Karl Popper comments that he who doesn’t believe in the second universe would do well to think about his own death—it is so obvious that a whole universe dies when a human being dies!

What I find nauseating in today’s academia is that it is an institution that denies the existence of this second universe. One could imagine what would happen if a student of psychology or psychiatry tried to write a lyric essay about why Nietzsche lost his mind, like the one that Stefan Zweig wrote and I have been excerpting for WDH. (And wait for the next chapters where Zweig’s story reaches its climax…)

A proper response to Stubbs would require an absolute break from the epistemological error, a category error, so ubiquitous in the academia. That is to say, we must approach such questions as if they were questions for our inner worlds.

The best way to respond to Stubbs, following what I have said about psychoclasses, is imagining that few whites have touched the black monolith of the film 2001. Those who have touched it—and here we are talking of the “second” universe that the current paradigm barely acknowledges—know that the most divine creature on Earth, the nymph, must be preserved at all costs.

This is not the sphere of objective science. Since we are talking of the ideals of our souls, let me confess that I became a white nationalist in 2009 when I lived in the Spanish island Gran Canaria, near Africa. The big unemployment that started in 2008 affected me and, without a job and completely broke, I spent a great deal of time in the internet. When I learned that a demographic winter was affecting all of the white population on planet Earth I was watching a Harry Potter film featuring a blondest female teenager. I remember that I told to myself something to the effect that, henceforward, I would defend the race with all of my teeth and claws.

However, to understand this universe I would have to tell the (tragic) story of the nymph Catalina: a pure white rose who happened to live around my home’s corner decades ago, who looked like the girl in that Parrish painting. But I won’t talk about the tragedy (something of it is recounted in Hojas Susurrantes). Suffice it to say that since then my mind has been devoted to her beauty and, by transference, it is now devoted to protect all genotype & phenotype that resembles hers…

Once we are talking from our own emergent universe (emergent compared to the Neanderthals who have not touched the monolith), Stubb’s questions are easily answered if one only dares to speak out what lies within our psyches:

So let me think of some fundamental questions that need to be answered: Why does it matter if the White race exists, if the rest of the humans are happy?

Speaks my inner universe: Because the rest of humans are like Neanderthals compared to Cro-Magnon whites. Here in Mexico I suffer real nightmares imagining the fate of the poor animals if whites go completely extinct (Amerinds are incapable of feeling the empathy I feel for our biological cousins).

Why does it matter if the White race continues to exist if I personally live my life out in comfort?

Speaks my inner universe: Because only pigs think like that. (Remember the first film of the Potter series, when Hagrid used magic to sprout a pig’s tail from Dudley’s fat bottom for gulping down Harry’s birthday cake.) We have a compromise with God’s creation even when a personal God does not exist.

Why should I be concerned with the White race if it only recently evolved from our ape-like ancestors, knowing that change is a part of the universe?

Speaks my inner universe: Because our mission is that we, not others, touch again the black monolith after four million years that one of our ancestors touched it.

Why should I be concerned with the existence of the White race if every White person is mortal, and preserving each one is futile?

Speaks my inner universe: It is a pity that no one has read The Yearling that I had been excerpting recently. I wanted to say something profound in the context of child abuse but that is a subject that does not interest WDH readers. Let me hint to what I thought after reading it.

To my mind the moral of the novel is not the moment when the father coerced his son to shoot Flag, but the very last page of Marjorie’s masterpiece. Suddenly Jody woke up at midnight and found himself exclaiming “Flag!” when his pet was already gone.

The poet Octavio Paz once said that we are mortals, yes: but those “portions of eternity,” as a boy playing with his yearling, are the sense of the universe. The empirical (now I am talking of the external) universe was created precisely to give birth to these simple subjective moments: figments that depict our souls like no other moments in the universe’s horizon of events.

Why should I be concerned with preserving the White race if all White people who live will suffer, some horribly, and none would suffer if they were wiped out?

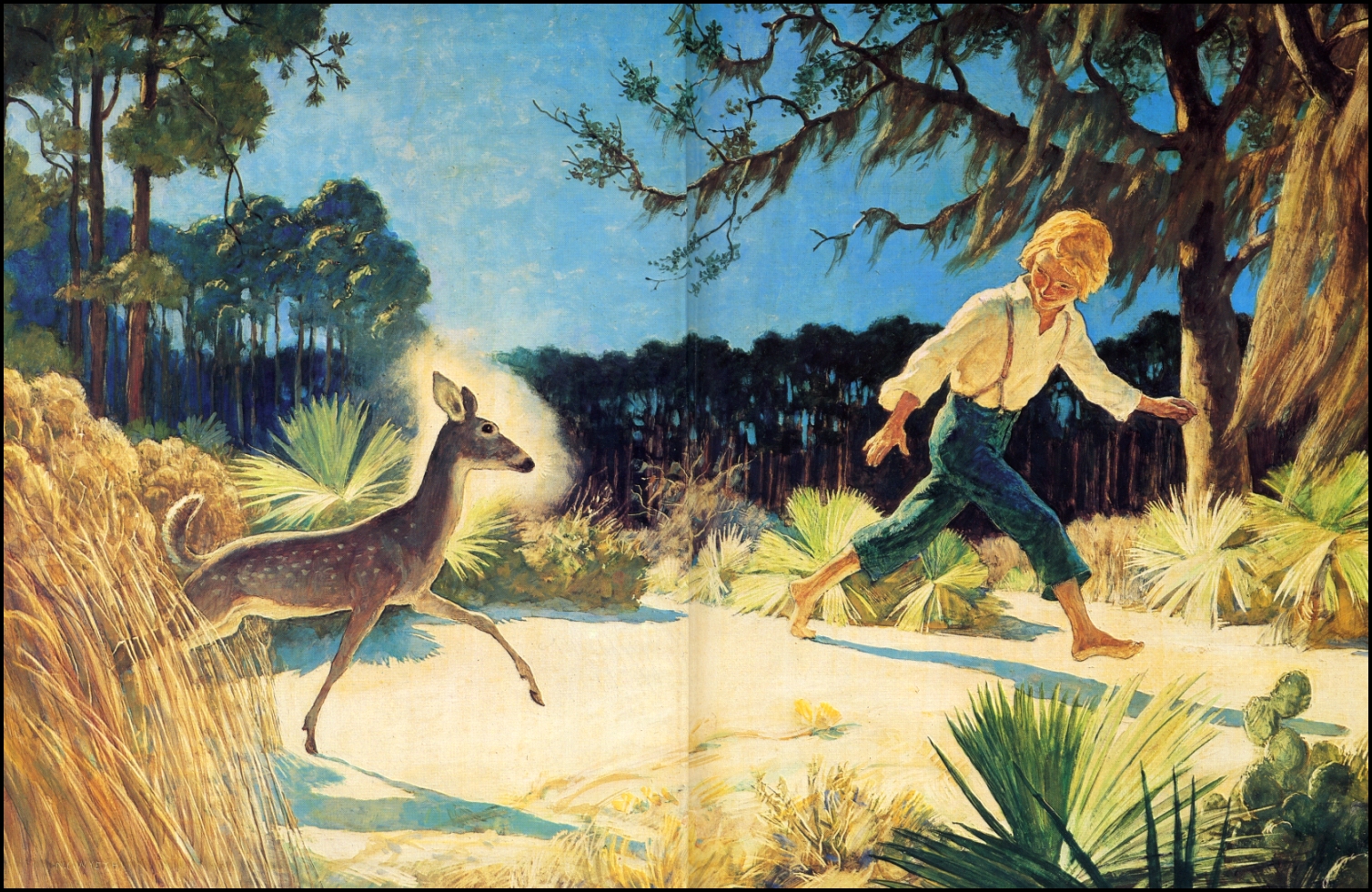

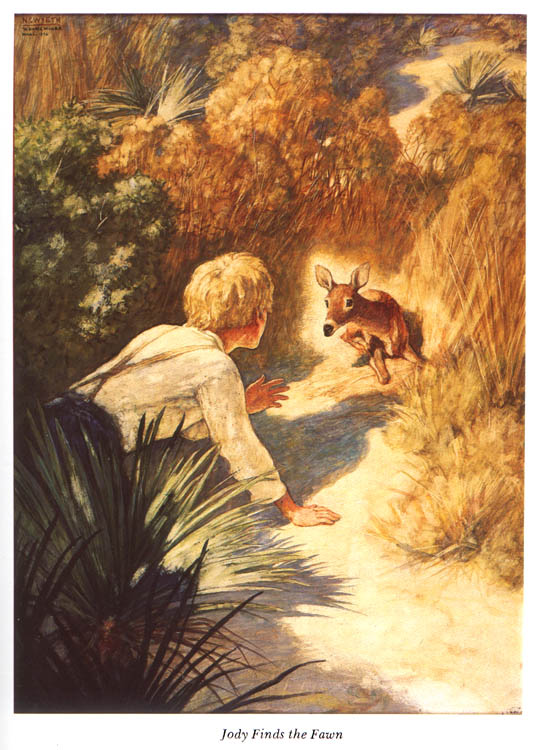

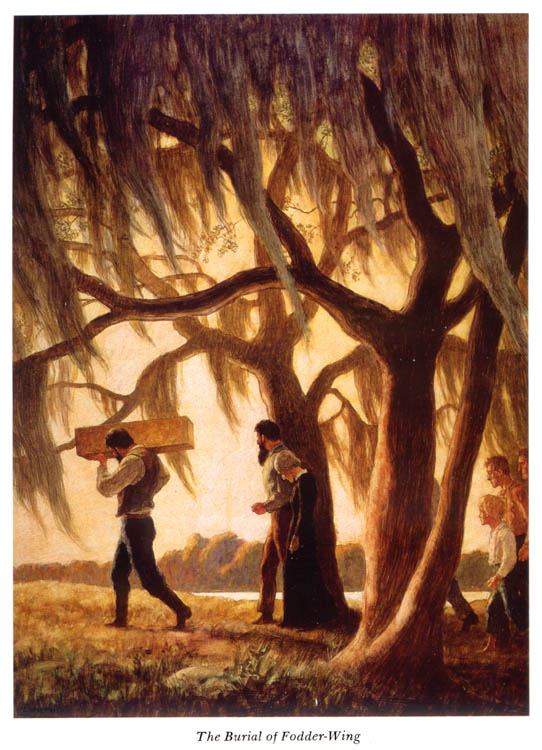

Speaks my inner universe: The boy suffered horribly when his father obliged him to murder Flag, yes. But the moment of eternity, as depicted in Wyeth’s illustration, had to be lived. It will probably leave a mark if another incarnation of the universe takes place…

The Yearling, 10

“Hey, Ma, Flag’ll soon be a yearlin’. Won’t he be purty, Ma, with leetle ol’ horns? Won’t his horns be purty?”

“He’d not look purty to me did he have a crown on. And angel’s wings.”

He followed her to cajole her. She sat down to look over the dried cow-peas in the pan. He rubbed his nose over the down of her cheek. He liked the furry feel of it.

“Ma, you smell like a roastin’ ear. A roastin’ ear in the sun.”

“Oh git along. I been mixin’ cornbread.”

“‘Tain’t that. Listen, Ma, you don’t keer do Flag have horns or no. Do you?”

“Hit’ll be that much more to butt and bother.”

He did not press the point. Flag was in increasing disgrace, at best. He had learned to slip free from the halter about his neck. When it was tightened so that he could not get out of it, he used the same tactics that a calf used against restraint. He strained against it until his eyes bulged and his breathing choked, and to save his perverse life, it was necessary to release him. Then when he was free, he raised havoc. There was no holding him in the shed. He would have razed it to the ground. He was wild and impudent. He was allowed in the house only when Jody was on hand to keep up with him. But the closed door seemed to make him possessed to enter. If it was not barred, he butted it open. He watched his chance and slipped in to cause some minor damage whenever Ma Baxter’s back was turned.

♣ ♣ ♣

I don’t want to add more excerpts. But I must say that an incident narrated in the rest of the tale, which I read this year, shocked me. I could easily write a long, detailed entry for my blog on Alice Miller, but child abuse is a subject that does not interest the readers of WDH.

A couple of days ago I caught my father telling his grandson that instead of watching TV for hours he should be reading the beautiful literature for young people, and he mentioned the beauty of a Julius Verne novel. But he’s a hypocrite, since his grandson does exactly what my father does: watching TV for hours everyday and, even in his late eighties, still going to the theater to watch Hollywood filth.

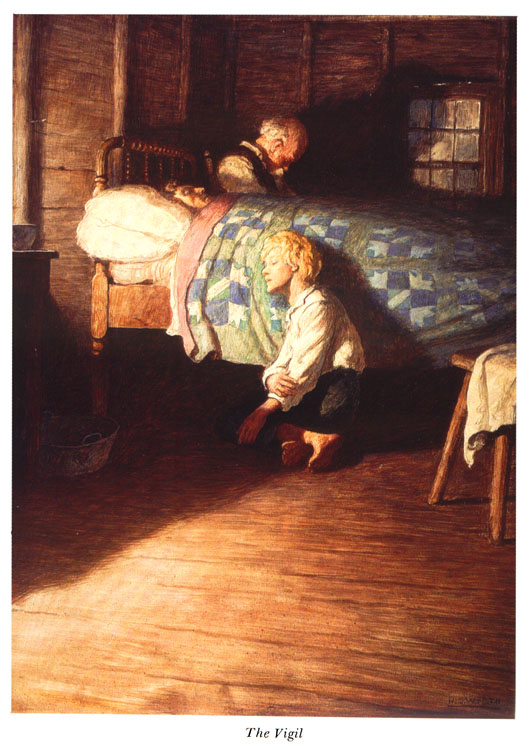

With classics like The Yearling I find it almost a sacrilege that adults are allowing their kids to watch TV. Although I only read The Yearling as an adult, I must say that as a child Wyeth’s illustrations provided some homely zest and a sense of trust in life and in one’s own parents that is difficult to transmit in words.

If anyone actually read the whole novel and is curious about why the culmination of the story surprised me so much, let me know and we can discuss it here.

Spoilers for those who haven’t read it!

The Yearling, 9

Now that I have been showing my colors—I believe that during and after the peak oil crises we can only save our white skins by returning to bucolic farming—, my initiative of adding excerpts of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ masterpiece might start to become apparent. But in fact it’s far more than that, as I will disclose in subsequent excerpts. For the moment suffice it to say that in the novel father and son visited grandma again:

In the morning, Penny said, “We got to agree now, will we stay with Grandma Hutto tonight or come home. Do we spend the night, Jody’s got to stay here to milk and feed the dogs and chickens.”

Jody said, “Trixie’s near about dry, Pa. And we kin leave feed. Leave me go, but please let’s stay with Grandma Hutto.”

Penny said to his wife, “You want to stay there tonight?”

“No, I don’t. Her and me don’t never swop much honey.”

“Then we’ll not stay. Jody, you kin go, but no teasin’ to stay after we git there.”

“What must I do with Flag? Cain’t he foller along so Grandma kin see him?”

Ma Baxter burst out, “That blasted fawn! They ain’t never been such a nuisance on the place, even countin’ you.”

He said with hurt pride, “I reckon I’ll jest stay here with him.”

Penny said, “Now boy, tie up the creetur and fergit him. He ain’t a dog, he ain’t a young un, though you’ve near about made one outen him. You cain’t carry him places like a gal would a play-dolly.”

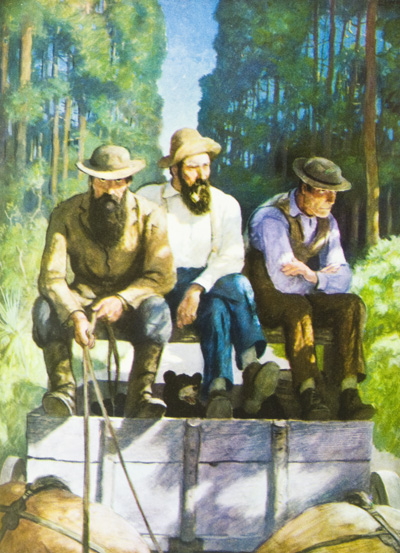

For sheer jealousness that a blonde married grandma’s son the Forresters (pic below) committed a mean act:

Penny said, “Must be a woods fire some’eres. Oh, my God.”

The position of the fire was unmistakable. Around the bend of the road, down the lane of oleanders, flames were shooting high into the air. Grandma Hutto’s house was burning. They turned into the yard. The house was a bonfire. The flames showed details of the rooms within. Fluff ran to them, his tail between his legs. They jumped down from the wagon.

The position of the fire was unmistakable. Around the bend of the road, down the lane of oleanders, flames were shooting high into the air. Grandma Hutto’s house was burning. They turned into the yard. The house was a bonfire. The flames showed details of the rooms within. Fluff ran to them, his tail between his legs. They jumped down from the wagon.

Grandma called, “Oliver! Oliver!”

It was impossible to approach within yards. Grandma ran toward the blaze. Penny pulled her back.

He shouted above the roaring and crackling, “You want to git burnt to death?”

“Oliver’s there! Oliver! Oliver!”

“He cain’t be. He’d of got out.”

“They’ve shot him! He’s in there! Oliver!”

He struggled with her. In the bright light the earth was plain. It was cut and trampled with the hooves of horses. But the Forresters and their mounts were gone.

Ma Baxter said, “There’s jest nothin’ them black buzzards won’t do.”

Grandma Hutto fought to break free.

Penny said, “Jody, for the Lord’s sake, drive back to Boyles’ store and see kin you find somebody seed where Oliver headed when he left the boat. If there’s nobody there, go on to the doin’s and find out from the stranger.”

Jody clambered to the wagon seat and turned Cæsar [the horse] back up the lane. His hands seemed wooden and he fumbled with the reins. He was panicked and could not remember whether his father had told him to go first to the doings or first to the store. If Oliver was alive, he would never be unfaithful to him, even in his mind, again. He turned into the road. The winter night was bright with stars. Cæsar snorted. A man and woman were walking down the road toward the river. He heard the man laugh.

He cried, “Oliver!” and jumped from the moving wagon.

Oliver called, “Now look who’s drivin’ around by hisself. Hey, Jody.”

The woman was Twink Weatherby.

Jody said, “Git in the wagon, quick, Oliver.”

“What’s the hurry? Where’s your manners? Speak to the lady.”

“Oliver, Grandma’s house is a-fire. The Forresters done it.”

Oliver tossed his bags into the wagon. He lifted Twink and swung her to the seat, then vaulted the wheel and took the reins. Jody scrambled up beside him. Oliver groped with one hand inside his shirt and laid his revolver on the seat.

“The Forresters is gone,” Jody said.

Oliver whipped the horse to a trot and turned down the lane. The frame of the house stood revealed around the flames, as though a box enclosed them. Oliver caught his breath.

“Ma wasn’t in it?”

“She’s yonder.”

Oliver stopped the wagon and they climbed down.

He called, “Ma!”

Grandma threw her arms in the air and ran to her son.

He said, “Easy, there, old lady. Quit tremblin’ now. Easy.”

Penny joined them.

He said, “No man’s voice was never more welcome, Oliver.”

Oliver pushed Grandma aside and stared at the house. The roof crashed and a fresh blaze leaped to the moss in the live oaks.

He said, “Which-a-way has the Forresters gone?”

Jody heard Grandma murmur, “Oh God.”

She braced herself.

She said loudly, “Now what in tarnation you want o’ the Forresters?”

Oliver wheeled.

“Jody said they done it.”

“Jody, you fool young un. The idees a boy’ll git. I left a lamp burnin’ by a open window. The curtain must of blowed and ketched. Hit worried me all through the evenin’ at the doin’s. Jody, you must want a ruckus mighty bad.”

Jody gaped at her. His mother’s mouth was open.

Ma Baxter said, “Why, you know–”

Jody saw his father grip her arm.

Penny said, “Yes, son, you got no business thinkin’ sich things of innocent men is miles away.”

Oliver let out his breath slowly.

He said, “I’m shore proud ’twasn’t their doin’. I’d not of left one alive.” He turned and drew Twink close to him. “Folks, meet my wife.”

Grandma Hutto wavered, then walked to the girl and kissed her cheek.

Grandma had to say goodbye to Florida and move to Boston with her son after the destruction of her homely, country cottage:

“Good-by, Grandma! Good-by, Oliver! Good-by, Twink!”

“Good-by, Jody–”

Their voices trailed away. It seemed to Jody that they were moving away from him into another world. It was as though he saw them die. There were rosy streaks across the east but the daylight seemed even colder than the night had been. The ashes of the Hutto house glowed faintly.

The Baxters drove home toward the scrub. Penny was wracked with sorrow for his friends. His face was strained. Jody was swept with so contradictory a tumult of thoughts that he gave up trying to sort them and snuggled down on the wagon-seat between the warmth of his mother and father.

But there still was consolation:

The cabin waited for him, and the smoke-house full of good meat, with old Slewfoot’s carcass added to it, and Flag. Above all, Flag. He could scarcely contain himself until he reached the shed. He had a tale to tell him.

The Yearling, 8

Flag was bored with the inactivity and wandered away. He was becoming bolder and was sometimes gone in the scrub for an hour or so. There was no holding him in the shed. He had learned to kick down the loose board walls. Ma Baxter expressed the belief, only because it was her hope, that the fawn was going wild and would eventually disappear. Jody was no longer even troubled by the remark.

Chechar’s note: But the fawn did something that he was not supposed to do.

Jody said, “He didn’t know what he was doin’.”

“I know, Jody, but the harm’s as bad to the ‘taters as if he done it for meanness. We got scarcely enough rations now to do the year.”

“Then I’ll not eat no ‘taters, and make it up.”

“Nobody wants you should do without ‘taters. You jest got to keep track o’ that scaper. If you keep him, it’s your place to see he don’t do no damage.”

“I couldn’t watch him and grind corn, all two.”

“Then keep him tied good in the shed when you cain’t watch him.”

“He hates that ol’ dark shed.”

“Then pen him.”

Jody rose before day the next morning and began work on a pen in the corner of the yard. He studied its position with an eye to using the fence for two corners of the pen, and to having it where he could see Flag from most of his own work-spots, the millstone, the wood-pile and the barn lot in particular. Flag would be content, he knew, if he was in sight of him. He finished the pen in the evening, when his chores were done. The next day he untied Flag from the shed and lifted him into the pen, kicking and struggling. Flag was over the bars and out and at his heels again before he reached the house. Penny found him again in tears.

Further ahead in the story:

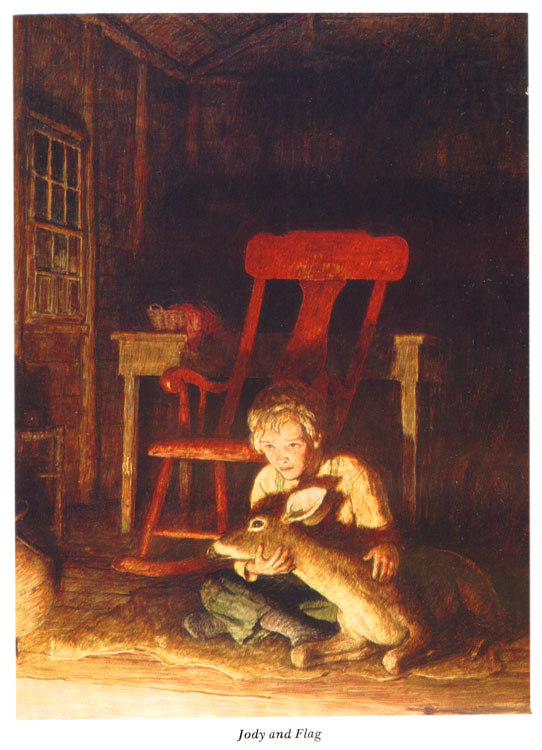

Jody rolled over on his side and stretched one arm across Flag. The fawn lay asleep, his legs tucked under his stomach, like a calf. His white tail twitched in his sleep. Ma Baxter did not mind his being in the house in the evening, after supper.

The wolves had invaded the lot and killed the heifer calf. A band of them, three dozen or more, milled about the enclosure. Their eyes caught the light in pairs, like corrupt pools of shining water.

“Now this be the kind o’ time a man needs a snort,” he said. “I shore aim to beg a quart offen the Forresters tomorrer.”

“You goin’ there tomorrer?”

“I got to have he’p. My dogs is all right, but a big woman and a leetle man and a yearlin’ boy is no match for that many hongry wolves huntin’ in a pack.”

And next morning…

Penny was back in time for dinner. He had eaten little breakfast and was hungry. He would not talk until he had eaten his fill. He lit his pipe and tilted back his chair. Ma Baxter washed the dishes and brushed out the floor with the palmetto sweep.

“All right,” Penny said, “I’ll tell you jest how it stand. Hit’s like I figgered, the wolves was about the worst destroyed by the plague of ary o’ the creeturs.”

“That’s it. I had me a good go-round with them jessies. We cain’t see it the same way about killin’ ’em. I want a couple o’ good hunts, and traps around our lot and their corral. But the Forresters is bent on pizenin’ ’em. Now I ain’t never pizened a creetur and I don’t aim to.”

Ma Baxter flung her dishcloth at the wall.

“Ezra Baxter, if your heart was to be cut out, hit’d not be meat. Hit’d be purely butter. You’re a plague-taked ninny, that’s what you be. Leave them wild things kill our stock cold-blooded, and us starve to death. But no, you’re too tender to give ’em a belly-ache.”

He sighed.

“Do seem foolish, don’t it? I jest cain’t he’p it. Anyways, innocent things is likely to git the pizen. Dogs and sich.”

“Better that, than the wolves clean us out.”

“Oh now Ory, they ain’t goin’ to clean us out. They ain’t like to bother Trixie nor Cæsar [the horse]. I mis-doubt could they git their teeth through their old hides. They shore ain’t goin’ to mess up with dogs that fights as good as mine. They ain’t goin’ to climb trees and ketch the chickens. They’s nary other thing here to bother, now the calf’s gone.”

“There’s Flag, Pa.”

It seemed to Jody that for once his father was wrong.

“Pizen’s no worse’n them tearin’ up the calf, Pa.”

“Tearin’ up the calf was nature. They was hongry. Pizen jest someway ain’t natural. Tain’t fair fightin’.”

Ma Baxter said, “Hit takes you to want to fight fair with a wolf, you–”

“Go ahead, Ory. Ease yourself and say it.”

“If I was to say it, hit’d take words I don’t scarcely know to think, let alone speak.”

“Then bust with it, wife. Pizenin’s a thing I jest won’t be a party to.”

He puffed on his pipe.

“If it’ll make you feel better,” he said, “the Forresters said worse’n you. I knowed they’d mock me in the head when I takened my stand, and they done so. And they’re fixin’ to go right ahead and set out the pizen.”

“I’m proud there’s men some’eres around.”

Jody glowered at both of them. His father was wrong, he thought, but his mother was unfair. Something in his father towered over the Forresters. The fact that this time the Forresters would not listen to him, must mean, not that he was not a man, but that he was mistaken. Perhaps, even, he was not wrong.

The passage shows that Jody’s father did have a higher degree of fairness and empathy toward the wild animals than his rude neighbors.

The Forrester poisoning killed thirty wolves in one week.

A fire was crackling on the kitchen hearth. His mother was placing a pan of biscuits in the Dutch oven. She had an old hunting coat of Penny’s over her long flannel nightgown. Her gray hair hung in braids over her shoulders. He went to her and smelled of her and rubbed his nose against her flannel breast. She felt big and warm and soft and he slipped his hands under the back of the coat to warm them. She tolerated him a moment, then pushed him away.

“I never had no hunter act like sich a baby,” she said. “You’ll be late for the meetin’ if breakfast’s late.”

Jody went with the adults to hunt those wolves that didn’t fall in the trap. The boy had to scare them by shooting and drive them towards the real hunters. Since he had done that alone, “Jody was white.”

Work was light and Jody spent long hours with Flag. The fawn was growing fast. His legs were long and spindling. Jody discovered one day that his light spots, the emblem of deer infancy, had disappeared. He examined the smooth hard head at once for signs of horns. Penny saw him at it and was obliged to laugh at him.

“You shore expect wonders, boy. He’ll be butt-headed ’til summer. He’ll not have no horns ’til he’s a yearlin’. Then they’ll be leetle ol’ spiky ones.”

Jody knew a content that filled him with a warm and lazy wonder. Even Oliver Hutto’s desertion and the Forresters’ withdrawal were distant ills that scarcely concerned him. Almost every day he took his gun and shot-bag and went to the woods with Flag. The black-jack oaks were no longer red but a rich brown. There was frost every morning. It made the scrub glitter like a forest full of Christmas trees. It reminded him that Christmas was not far away.

The Yearling, 7

For two weeks Penny concerned himself with the salvaging of crops. The sweet potatoes were not ready, by two months, for digging. But they were rotting and would be a total loss if they were not dug. Jody worked long hours at them.

The smell of death lay everywhere.

Penny said uneasily, “Somethin’s wrong. That stink’s due to be done with. Things is yit dyin’.”

A month after the flood, in October, he returned with Jody in the wagon beside him to Mullet Prairie to gather the cut and cured hay. Rip and Julia trotted along behind the wagon. Penny allowed Flag, too, to follow for he had begun to make a great commotion whenever he was shut up and left behind in the shed.

(Chechar’s note: But even so they continued to hunt deers…)

Penny stopped the wagon and took up his gun and went with Jody over the fence to the dogs. A buck deer lay in the corner. It shook its head, making a menacing motion with its horns. Penny lifted his gun, then lowered it.

“Now that buck’s sick, too.”

He approached close and the deer did not move. Its tongue lolled. Julia and Rip were in a frenzy. They could not understand the refusal of live game either to run or to fight.

“No use to waste shot.”

He took his knife from its scabbard and went to the deer and slit its throat. It died with the quiet of a thing to whom death is only one short step beyond a present misery. He drove off the dogs and examined it carefully. Its tongue was black and swollen. Its eyes were red and watery. It was as thin as the dying wild-cat.

He said, “This is worse’n I figgered. A plague has hit the wild creeturs. Hit’s the black tongue.”

Jody had heard of human plagues. The wild animals had always seemed to him to be charmed, and beyond all human ills. A creature died in the chase, or when another creature, more powerful, pounced and destroyed. Death in the scrub was clean and violent, never a slow sickness and lingering. He stared down at the dead deer.

He said, “We’ll not eat it, will we?”

Penny shook his head.

“Tain’t fitten.”

The dogs were sniffing farther down the fence-row. Julia barked again. Penny looked after her. A pile of carcasses lay in a heap. Two old bucks and a yearling had died together. Jody had seldom seen his father’s face so grave. Penny examined the plague-killed deer and turned away without speaking. Death seemed to have appeared wholesale out of the air.

“What done it, Pa? What kilt ’em?”

Again Penny shook his head.

“I’ve never knowed what give the black tongue. Mebbe hit’s the flood water, full o’ dead things, has got pizenous.”

A fear shot through Jody like a hot knife.

“Pa–Flag. He’ll not get it, will he?”

“Son, I’ve told you all I know.”

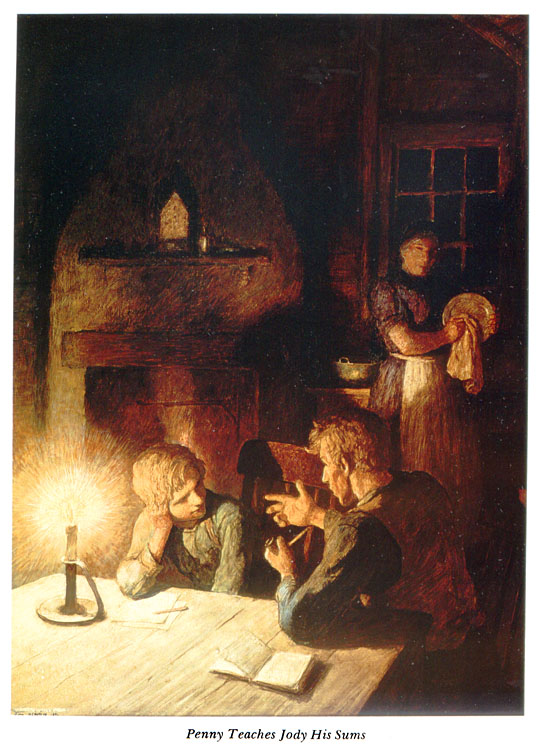

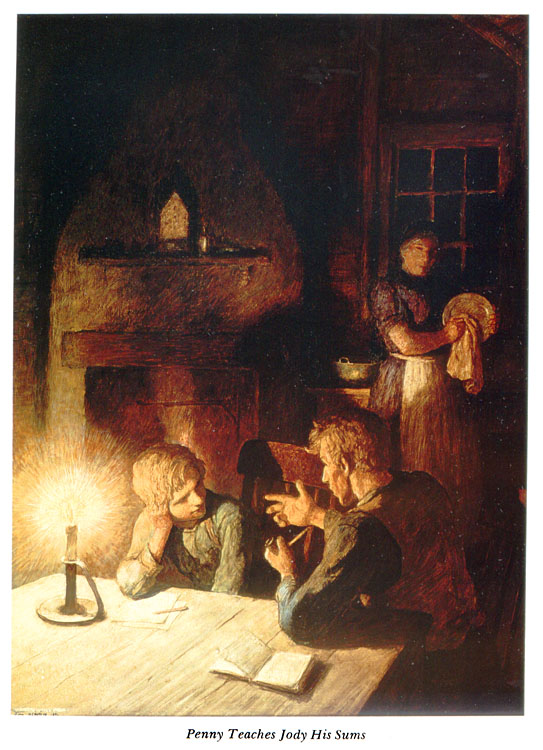

Penny said, “I hope you do a heap of it, for the flood’s done you outen a teacher. The Forresters and me had it settled to board a teacher between us for you and Fodder-wing this winter. When Fodder-wing died, I still figgered I’d do some trappin’ and git cash money that-a-way. But the creeturs is so scarcet now and the hides so pore, hit’s no use.”

This is the image that my dad showed me when I was a kid. He told me that the illustration was beautiful as it reflected how a dad taught his son with a loving mother in the background (with very, very different words of course).

Jody said comfortingly, “That’s all right. I know a heap now.”

“That jest proves your ignorance, young feller. I do hate for you to grow up and not know nothin’. You’ll jest have to make out this year with what leetle I kin learn you.”

The Yearling, 6

Pages after we read a vignette where Penny’s wife is depicted:

He said, “Ory, the day may come when you’ll know the human heart is allus the same. Sorrer strikes the same all over. Hit makes a different kind o’ mark in different places. Seems to me, times, hit ain’t done nothin’ to you but sharpen your tongue.”

She sat down abruptly.

She said, “Seems like bein’ hard is the only way I kin stand it.”

He left his breakfast and went to her and stroked her hair.

“I know. Jest be a leetle mite easy on t’other feller.”

The next chapter describes the autumn month to get the hogs butchered while, “Flag grew miraculously, day by day. He liked best to play with Jody.” But there was an obscure shadow in that bucolic world…

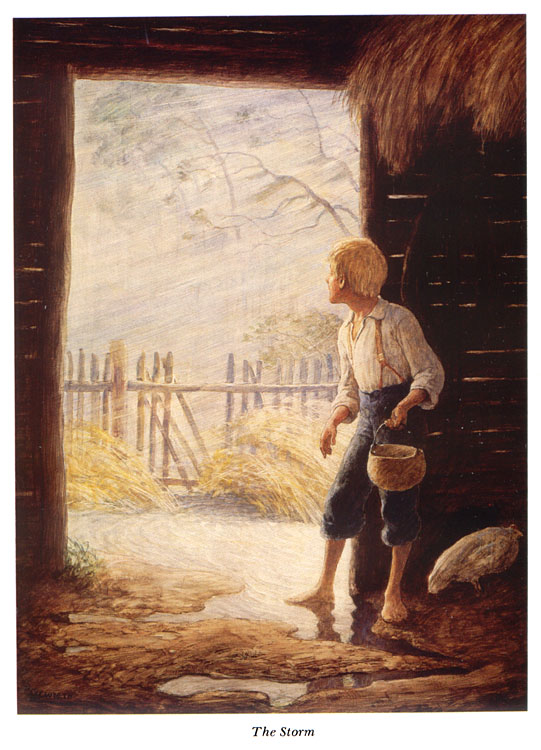

He said to Jody, “Now them ocean Jessies don’t belong to be crossin’ Floridy. I don’t like it. Hit means bad weather, and when I say bad, I mean bad.”

The sun set strangely that night. The sunset was not red, but green. The fawn came to Jody’s bed and poked its muzzle against his face.

Jody asked, “Is it a hurricane comin?”

“I don’t think. But somethin’s comin’, ain’t natural.”

In mid-afternoon the skies turned so black that the chickens went to roost.

And pages later:

Penny said after him, “Don’t he look like a wet yearlin’ crane. All he needs is tail feathers. My, ain’t he growed since spring.”

There was a lull in the fierce beating wind. A pitiful whine sounded at the door. Penny went to it. Rip had found adequate shelter, but old Julia stood drenched and shivering. Or perhaps she had found shelter, too, but longed for a comfort that was more than dryness. Penny let her in.

Ma Baxter said, “Now let in Trixie and old Cæsar [the farm’s animals], and you’ll have things about to suit you.”

Penny said to Julia, “Jealous o’ leetle ol’ Flag, eh? Now you’ve been a Baxter longer’n Flag. You jest come dry yourself.”

She wagged her slow tail and licked his hand. Jody was warmed by his father’s inclusion of the fawn in the family. Flag Baxter–

Ma Baxter said, “How you men kin take on over a dumb creetur, I cain’t see. Callin’ a dog by your own name–And that fawn, sleepin’ right in the bed with Jody.”

Jody said, “He don’t seem like a creetur to me, Ma. He seems jest like another boy.”

“Well, it’s your bed. Long as he don’t bring fleas or lice or ticks or nothin’ into it.”

He was indignant.

“Look at him, Ma. Lookit that sleekity coat. Smell him, Ma.”

“I don’t want to smell him.”

“But he smells sweet.”

“Jest like a rose, I s’pose. Well, to my notion, wet fur’s wet fur.”

The rain drummed on the roof. The wind whistled under the eaves. Old Julia stretched out on the floor near the fawn. The storm was as cozy as Jody had hoped for. He made up his mind privately that he would wish for another in a week or two. Now and then Penny peered out of the window into the dark.

They worked until noon in the down-pour, pulling the slippery pods from the bushes. They came in for a hurried dinner and went back again without troubling to change their clothes. They covered most of the field.

The second day after the storm, Buck and Mill-wheel Forrester came riding to the island to see whether all was well with the Baxters. They had come straight from their own work of caring for the stranded stock. Along the main trail the sights, they said, were new in their generation. The flood had played havoc with the small animals. It was agreed that the four of them, Buck and Mill-wheel and Penny and Jody, should make a tour of exploration for some miles around, so that they might know what to expect, in the immediate future, of the movements not only of the game, but of the predatory creatures. The Forresters had brought two dogs, and an extra horse, and asked to have Rip and Julia join them. Jody was excited that he was to be taken.

Then they went to Silver Glen and in Lake George they saw something that shocked them:

Penny said, “I didn’t know there was that many snakes in the world.”

The bodies of highland reptiles were as thick as cane-stalks. There were dead rattlesnakes, king snakes, black snakes, coach whips, chicken snakes, garter snakes and coral snakes. At the thin edge of the receding water, cottonmouth moccasins and other water snakes swam about thickly.

Wild-cats and lynxes peered visibly from the branches of trees. The Forresters urged their killing.

Penny said, “Hit’s a pity we should add to their troubles. Seems like there’d ought to be room enough in the world for folks and creeturs, both.”

Later at night:

Jody put his arms under his head and looked up into the sky. It was as thick with stars as a pool of silver minnows.

The Yearling, 5

The fawn blinked its eyelids. It groaned comfortably and dropped its head. He tiptoed from the shed. No dog, he thought, could be more biddable.

Jody scraped his plate clean and set it aside. He lay down beside the fawn. He put one arm across its neck. It did not seem to him that he could ever be lonely again.

After describing the lovely interaction of boy and baby fawn right after the new pet arrived to the Baxters’ farm, in the next chapter Marjorie wrote:

The fawn took up much of Jody’s time. It tagged him wherever he went. At the woodpile, it interfered with the swing of his axe. The milking had been assigned to him. He was forced to bar the fawn from the lot and it stood by the gate, peering between the bars, and bleated until he had finished. He stripped Trixie’s teats until she kicked in protest. Each cupful of milk meant more nourishment for the fawn. It seemed to him that he could see it growing. It stood firm on its small legs and leaped and tossed its head and tail. He romped with it until they dropped together in a heap to rest and cool themselves.

Accompanied with the family guest, in the next week Jody went out to steal some honey from the industrious bees:

He started across the yard with Jody beside him. The fawn was close behind.

“You want your blasted baby to git stung to death? Then shut him up. With me gone, you’ll not have no time to nuss that fawn.”

With his health recovered Penny visits the Forresters:

He asked innocently, “How did you-all come out with that sorry dog I traded you?”

Buck drawled, “Why, that dog’s proved out the fastest and the finest and the hardest-huntin’ and the fearlessest of ary dog we’ve ever had on the place. All he needed was men to train him.”

Penny chuckled.

He said, “I’m proud you was smart enough to make somethin’ outen him. Where’s he now?”

“Well, he was so blasted good, he put t’other dogs so to shame, Lem couldn’t abide it, and he hauled off and shot him and buried him in the Baxter cemetery one night.”

Jody asked, “If fellers didn’t say quarrelin’ things, would they put in to fight?”

Penny said, “I’m feered so. I oncet seed a pair o’ deef dummies havin’ it. But they do say they got a sign language, and likely one passed the insult in a sign.”

Buck said, “Hit’s male nature, boy. Wait ’til you git to courtin’ and you’ll git your breeches dusted many a time.”

“But nobody but Lem and Oliver was courtin’, and here all us Baxters and all you Forresters was in to it.”

Penny said, “They’s no end to what a man’ll fight for. I even knowed a preacher takened off his coat and fit ary man wouldn’t agree to infant damnation.”

Anybody who has read the fifth book of my Hojas Susurrantes knows why such a passage can make an impression in my mind. Later in the novel Marjorie says:

Jody waited until a deep rumbling snore sounded. Then he slipped from the house and groped his way to the shed. The fawn stood up at the sound. He felt his way to it and threw his arms around its neck. It nuzzled his cheek. He lay with his head against its side. Its ribs lifted and fell with its breathing.

The fawn lay in the hedge-row in the shade of an elderberry bush. It had been almost a nuisance when he began his work. It had galloped up and down the sweet potato beds, trampling the vines, and knocking down the edges of the beds. It had come and stood in front of him in the direct path of his hoeing, refusing to move, to force him to play with it. The wide-eyed, wondering expression of its first weeks with him had given way to an alert awareness. Jody liked to work with it near.

The boy called Fodder-wing died, the only human friend of Jodie. At the Forresters’ home Jodie did not know that before dying Fodder-wing had envisioned a name for his pet:

The boy called Fodder-wing died, the only human friend of Jodie. At the Forresters’ home Jodie did not know that before dying Fodder-wing had envisioned a name for his pet:

“Why,” she said, “he named it. Last time he talked about it, he gave it a name. He said, ‘A fawn carries its flag so merry. A fawn’s tail’s a leetle white merry flag. If I had me a fawn, I’d name him “Flag.” “Flag the fawn,” is what I’d call him.'”

Jody repeated, “Flag.”

He thought he would burst. Fodder-wing had talked of him and had named the fawn. There was happiness tangled with his grief that was both comforting and unbearable.

He said, “I reckon I best go feed him. I best go feed Flag.”

The Yearling, 4

The thought of the fawn returned to him. A leaden feeling came over him again. It would be desperate with hunger this morning. He wondered if it would try to nurse the cold teats of the doe. The open flesh of the dead deer would attract the wolves. Perhaps they had found the fawn and had torn its soft body to ribbons. His joy in the morning, in his father’s living, was darkened and tainted. His mind followed the fawn and would not be comforted.

That very day, with the neighbors taking care of Penny:

Jody was proud of the table. There were not as many different dishes as the Forresters served, but there was enough of everything. The men ate greedily. At last they pushed away their plates and lit their pipes.

Mill-wheel said, “Seems like Sunday, don’t it?”

Ma Baxter said, “Sickness allus do seem like Sunday, someway. Folks settin’ around, and the men not goin’ to the field.”

Jody had never seen her so amiable. She had waited to eat until the men were done, for fear of their not having plenty. She sat now eating with relish. The men chatted idly. Jody allowed his thoughts to drift back to the fawn. He could not keep it out of his mind.

The way the good doctor refused payment from the poor family cannot contrast more with our culture dedicated to the glory of Mammon:

She said, “Well. What do we owe you, Doc? We cain’t pay right now, but time the crops is made—”

“Pay for what? I’ve done nothing. He was safe before I got here. I’ve had a night’s lodging and a good breakfast. Send me some syrup when your cane’s ground.”

“You’re mighty good, Doc. We been scramblin’ so, I didn’t know folks could be so good.”

“Hush, woman. You got a good man there. Why wouldn’t folks be good to him?”

Buck said, “You reckon that ol’ horse o’ Penny’s kin keep ahead o’ me at the plow? I’m like to run him down.”

Doc said, “Get as much milk down Penny as he’ll take. Then give him greens and fresh meat, if you can get it.”

Buck said, “Me and Jody’ll tend to that.”

Mill-wheel said, “Come on, boy. We got to git ridin’.”

Ma Baxter asked anxiously, “You’ll not be gone long?”

Jody said, “I’ll be back shore, before dinner.”

“Reckon you’d not git home a-tall,” she said, “if ’twasn’t for dinner-time.”

Doc said, “That’s man-nature, Ma’am. Three things bring a man home again—his bed, his woman, and his dinner.”

Buck and Mill-wheel guffawed. Doc’s eye caught the cream-colored ‘coonskin knapsack.

“Now ain’t that a pretty something? Wouldn’t I like such as that to tote my medicines?”

Jody had never before possessed a thing that was worth giving away. He took it from its nail, and put it in Doc’s hands.

“Hit’s mine,” he said. “Take it.”

When the boy and Mill-wheel Forrester left the home looking for the fawn:

Suddenly Jody was unwilling to have Mill-wheel with him. If the fawn was dead, or could not be found, he could not have his disappointment seen. And if the fawn was there, the meeting would be so lovely and so secret that he could not endure to share it.

But Jody alone found it:

Movement directly in front of him startled him so that he tumbled backward. The fawn lifted its face to his. It turned its head with a wide, wondering motion and shook him through with the stare of its liquid eyes. It was quivering. It made no effort to rise or run. Jody could not trust himself to move.

He whispered, “It’s me.”

The fawn lifted its nose, scenting him. He reached out one hand and laid it on the soft neck. The touch made him delirious. He moved forward on all fours until he was close beside it. He put his arms around its body. A light convulsion passed over it but it did not stir. He stroked its sides as gently as though the fawn were a china deer and he might break it. Its skin was softer than the white ‘coonskin knapsack. It was sleek and clean and had a sweet scent of grass. He rose slowly and lifted the fawn from the ground. It was no heavier than old Julia. Its legs hung limply. They were surprisingly long and he had to hoist the fawn as high as possible under his arm.

He was afraid that it might kick and bleat at sight and smell of its mother. He skirted the clearing and pushed his way into the thicket. It was difficult to fight through with his burden. The fawn’s legs caught in the bushes and he could not lift his own with freedom. He tried to shield its face from prickling vines. Its head bobbed with his stride. His heart thumped with the marvel of its acceptance of him. He reached the trail and walked as fast as he could until he came to the intersection with the road home. He stopped to rest and set the fawn down on its dangling legs. It wavered on them. It looked at him and bleated.

He said, enchanted, “I’ll tote you time I git my breath.”

He remembered his father’s saying that a fawn would follow that had been first carried. He started away slowly. The fawn stared after him. He came back to it and stroked it and walked away again. It took a few wobbling steps toward him and cried piteously. It was willing to follow him. It belonged to him. It was his own. He was light-headed with his joy. He wanted to fondle it, to run and romp with it, to call to it to come to him. He dared not alarm it. He picked it up and carried it in front of him over his two arms. It seemed to him that he walked without effort. He had the strength of a Forrester.

His arms began to ache and he was forced to stop again. When he walked on, the fawn followed him at once. He allowed it to walk a little distance, then picked it up again. The distance home was nothing. He could have walked all day and into the night, carrying it and watching it follow. He was wet with sweat but a light breeze blew through the June morning, cooling him. The sky was as clear as spring water in a blue china cup. He came to the clearing. It was fresh and green after the night’s rain. He could see Buck Forrester following old Cæsar at the plow in the cornfield. He thought he heard him curse the horse’s slowness. He fumbled with the gate latch and was finally obliged to set down the fawn to manage it. It came to him that he would walk into the house, into Penny’s bedroom, with the fawn walking behind him. But at the steps, the fawn balked and refused to climb them. He picked it up and went to his father. Penny lay with closed eyes.

Jody called, “Pa! Lookit!”

Penny turned his head. Jody stood beside him, the fawn clutched hard against him. It seemed to Penny that the boy’s eyes were as bright as the fawn’s. His face lightened, seeing them together.

He said, “I’m proud you found him.”

“Pa, he wa’n’t skeert o’ me. He were layin’ up right where his mammy had made his bed.”

“The does learns ’em that, time they’re borned. You kin step on a fawn, times, they lay so still.”

“Pa, I toted him, and when I set him down, right off he follered me. Like a dog, Pa.”

“Ain’t that fine? Let’s see him better.”

Jody lifted the fawn high. Penny reached out a hand and touched its nose. It bleated and reached hopefully for his fingers.

He said, “Well, leetle feller. I’m sorry I had to take away your mammy.”

“You reckon he misses her?”

“No. He misses his rations and he knows that. He misses somethin’ else but he don’t know jest what.”

Ma Baxter came into the room.

“Look, Ma, I found him.”

“I see.”

“Ain’t he purty, Ma? Lookit them spots all in rows. Lookit them big eyes. Ain’t he purty?”

“He’s powerful young. Hit’ll take milk for him a long whiles. I don’t know as I’d of give my consent, if I’d knowed he was so young.”

Penny said, “Ory, I got one thing to say, and I’m sayin’ it now, and then I’ll have no more talk of it. The leetle fawn’s as welcome in this house as Jody. It’s hissen. We’ll raise it without grudgment o’ milk or meal. You got me to answer to, do I ever hear you quarrelin’ about it. This is Jody’s fawn jest like Julia’s my dog.”

Jody had never heard his father speak to her so sternly. The tone must hold familiarity for his mother, however, for she opened and shut her mouth and blinked her eyes.

She said, “I only said it was young.”

“All right. So it is.”

He closed his eyes.

The Yearling, 3

“Ma, we got milk a-plenty. Cain’t I git me a leetle ol’ fawn for a pet for me? A spotted fawn, Ma. Cain’t I?”

This was exactly the sort of dialogue that, as an adult, I expected to read in a novel I had only known from its illustrations. But this—:

Jody picked up his gun and started away. He would give anything to bring down a buck alone.

The buck lay in the shade of the live oak. Penny had already begun the dressing.

—I would have never, ever imagined as the child I was.

He said, “I wisht we could git our meat without killin’ it.”

“Hit’s a pity, a’right. But we got to eat.”

Penny was working deftly. His hunting knife, a flat saw-file ground down to an edge, with only a corn-cob for handle, was not overly sharp, but he had already drawn the venison and cut off the heavy head. He skinned it below the knees, crossed the legs and tied them, slipped his arms through the junctures, and stood up with the carcass neatly balanced on his back for carrying.

As I child I naively thought that all of the contents of the novel would be as bucolic as Wyeth’s illustrations. Those idyllic child memories explain the surprise I felt as the adult who, decades later, actually read the novel’s contents including lots of skinning of dead animals.

The chapter that introduces Grandma Hutto contains a passage that throws light onto the character of Jody’s mother:

Penny went to the rear of the cottage with the venison and the hide. They were all welcome here, father and son and battle-scarred hound. Jody felt more at home than when he returned to his own mother.

He said, “I reckon you wouldn’t be so proud to see me, did you have to put up with me all the time.”

Grandma chuckled.

“You’ve heard your Ma say that. Did she quarrel about you comin?”

“Not so turrible as sometimes.”

“Your father,” she said tartly, “married a woman all Hell couldn’t amuse.”

Despite the numerous hunting and skinning of animal bodies, Jody was a compassionate kid.

He recalled a wild-cat that the dogs had torn to pieces. Wild-cats deserved what they got. Yet at one moment, when the snarling mouth had gaped wide in agony, and the evil eyes had filmed in dying, he had been stabbed with pity.

Later the Forresters stole from the Baxters some pigs which Penny wanted back. With Jody he was on route to the Forrester’s place trying to pick a fight but was bitten by a rattlesnake. Addressing his son—:

He said quietly, “I cain’t do it no more good. I’m goin’ on home. You go to the Forresters and git ’em to ride to the Branch for Doc Wilson.”

“Reckon they’ll go?”

“We got to chance it. Call out to ’em quick, sayin’, afore they chunk somethin’ at you or mebbe shoot.”

A hunted doe’s liver and heart were used to absorb the snake’s venom.

He turned back to pick up the beaten trail. Jody followed. Over his shoulder he heard a light rustling. He looked back. A spotted fawn stood peering from the edge of the clearing, wavering on uncertain legs. Its dark eyes were wide and wondering.

He called out, “Pa! The doe’s got a fawn.”

“Sorry, boy. I cain’t he’p it. Come on.”

An agony for the fawn came over him. He hesitated. It tossed its small head, bewildered. It wobbled to the carcass of the doe and leaned to smell it. It bleated.

Penny called, “Git a move on, young un.”

On route to the Forresters’ home Jody—:

had never minded night or darkness, but Penny had always been in front of him.

Dr Wilson spent the night with the Baxters trying to save Penny’s life. Jody was worried of both, his father and the little orphan:

He remembered the fawn. He sat upright.

The fawn was alone in the night, as he had been alone. The catastrophe that might take his father had made it motherless.

The fawn was alone in the night, as he had been alone. The catastrophe that might take his father had made it motherless.

It had lain hungry and bewildered through the thunder and rain and lightning, close to the devastated body of its dam, waiting for the stiff form to arise and give it warmth and food and comfort. He pressed his face into the hanging covers of the bed and cried bitterly. He was torn with hate for all death and pity for all aloneness.