The thought of the fawn returned to him. A leaden feeling came over him again. It would be desperate with hunger this morning. He wondered if it would try to nurse the cold teats of the doe. The open flesh of the dead deer would attract the wolves. Perhaps they had found the fawn and had torn its soft body to ribbons. His joy in the morning, in his father’s living, was darkened and tainted. His mind followed the fawn and would not be comforted.

That very day, with the neighbors taking care of Penny:

Jody was proud of the table. There were not as many different dishes as the Forresters served, but there was enough of everything. The men ate greedily. At last they pushed away their plates and lit their pipes.

Mill-wheel said, “Seems like Sunday, don’t it?”

Ma Baxter said, “Sickness allus do seem like Sunday, someway. Folks settin’ around, and the men not goin’ to the field.”

Jody had never seen her so amiable. She had waited to eat until the men were done, for fear of their not having plenty. She sat now eating with relish. The men chatted idly. Jody allowed his thoughts to drift back to the fawn. He could not keep it out of his mind.

The way the good doctor refused payment from the poor family cannot contrast more with our culture dedicated to the glory of Mammon:

She said, “Well. What do we owe you, Doc? We cain’t pay right now, but time the crops is made—”

“Pay for what? I’ve done nothing. He was safe before I got here. I’ve had a night’s lodging and a good breakfast. Send me some syrup when your cane’s ground.”

“You’re mighty good, Doc. We been scramblin’ so, I didn’t know folks could be so good.”

“Hush, woman. You got a good man there. Why wouldn’t folks be good to him?”

Buck said, “You reckon that ol’ horse o’ Penny’s kin keep ahead o’ me at the plow? I’m like to run him down.”

Doc said, “Get as much milk down Penny as he’ll take. Then give him greens and fresh meat, if you can get it.”

Buck said, “Me and Jody’ll tend to that.”

Mill-wheel said, “Come on, boy. We got to git ridin’.”

Ma Baxter asked anxiously, “You’ll not be gone long?”

Jody said, “I’ll be back shore, before dinner.”

“Reckon you’d not git home a-tall,” she said, “if ’twasn’t for dinner-time.”

Doc said, “That’s man-nature, Ma’am. Three things bring a man home again—his bed, his woman, and his dinner.”

Buck and Mill-wheel guffawed. Doc’s eye caught the cream-colored ‘coonskin knapsack.

“Now ain’t that a pretty something? Wouldn’t I like such as that to tote my medicines?”

Jody had never before possessed a thing that was worth giving away. He took it from its nail, and put it in Doc’s hands.

“Hit’s mine,” he said. “Take it.”

When the boy and Mill-wheel Forrester left the home looking for the fawn:

Suddenly Jody was unwilling to have Mill-wheel with him. If the fawn was dead, or could not be found, he could not have his disappointment seen. And if the fawn was there, the meeting would be so lovely and so secret that he could not endure to share it.

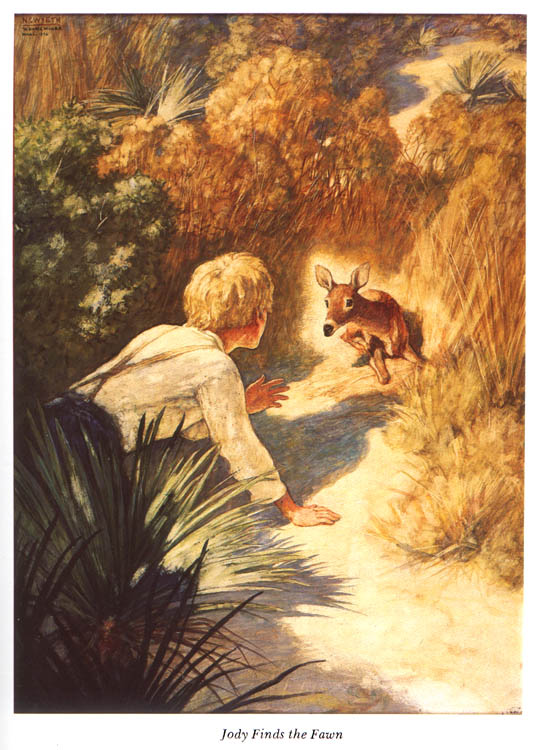

But Jody alone found it:

Movement directly in front of him startled him so that he tumbled backward. The fawn lifted its face to his. It turned its head with a wide, wondering motion and shook him through with the stare of its liquid eyes. It was quivering. It made no effort to rise or run. Jody could not trust himself to move.

He whispered, “It’s me.”

The fawn lifted its nose, scenting him. He reached out one hand and laid it on the soft neck. The touch made him delirious. He moved forward on all fours until he was close beside it. He put his arms around its body. A light convulsion passed over it but it did not stir. He stroked its sides as gently as though the fawn were a china deer and he might break it. Its skin was softer than the white ‘coonskin knapsack. It was sleek and clean and had a sweet scent of grass. He rose slowly and lifted the fawn from the ground. It was no heavier than old Julia. Its legs hung limply. They were surprisingly long and he had to hoist the fawn as high as possible under his arm.

He was afraid that it might kick and bleat at sight and smell of its mother. He skirted the clearing and pushed his way into the thicket. It was difficult to fight through with his burden. The fawn’s legs caught in the bushes and he could not lift his own with freedom. He tried to shield its face from prickling vines. Its head bobbed with his stride. His heart thumped with the marvel of its acceptance of him. He reached the trail and walked as fast as he could until he came to the intersection with the road home. He stopped to rest and set the fawn down on its dangling legs. It wavered on them. It looked at him and bleated.

He said, enchanted, “I’ll tote you time I git my breath.”

He remembered his father’s saying that a fawn would follow that had been first carried. He started away slowly. The fawn stared after him. He came back to it and stroked it and walked away again. It took a few wobbling steps toward him and cried piteously. It was willing to follow him. It belonged to him. It was his own. He was light-headed with his joy. He wanted to fondle it, to run and romp with it, to call to it to come to him. He dared not alarm it. He picked it up and carried it in front of him over his two arms. It seemed to him that he walked without effort. He had the strength of a Forrester.

His arms began to ache and he was forced to stop again. When he walked on, the fawn followed him at once. He allowed it to walk a little distance, then picked it up again. The distance home was nothing. He could have walked all day and into the night, carrying it and watching it follow. He was wet with sweat but a light breeze blew through the June morning, cooling him. The sky was as clear as spring water in a blue china cup. He came to the clearing. It was fresh and green after the night’s rain. He could see Buck Forrester following old Cæsar at the plow in the cornfield. He thought he heard him curse the horse’s slowness. He fumbled with the gate latch and was finally obliged to set down the fawn to manage it. It came to him that he would walk into the house, into Penny’s bedroom, with the fawn walking behind him. But at the steps, the fawn balked and refused to climb them. He picked it up and went to his father. Penny lay with closed eyes.

Jody called, “Pa! Lookit!”

Penny turned his head. Jody stood beside him, the fawn clutched hard against him. It seemed to Penny that the boy’s eyes were as bright as the fawn’s. His face lightened, seeing them together.

He said, “I’m proud you found him.”

“Pa, he wa’n’t skeert o’ me. He were layin’ up right where his mammy had made his bed.”

“The does learns ’em that, time they’re borned. You kin step on a fawn, times, they lay so still.”

“Pa, I toted him, and when I set him down, right off he follered me. Like a dog, Pa.”

“Ain’t that fine? Let’s see him better.”

Jody lifted the fawn high. Penny reached out a hand and touched its nose. It bleated and reached hopefully for his fingers.

He said, “Well, leetle feller. I’m sorry I had to take away your mammy.”

“You reckon he misses her?”

“No. He misses his rations and he knows that. He misses somethin’ else but he don’t know jest what.”

Ma Baxter came into the room.

“Look, Ma, I found him.”

“I see.”

“Ain’t he purty, Ma? Lookit them spots all in rows. Lookit them big eyes. Ain’t he purty?”

“He’s powerful young. Hit’ll take milk for him a long whiles. I don’t know as I’d of give my consent, if I’d knowed he was so young.”

Penny said, “Ory, I got one thing to say, and I’m sayin’ it now, and then I’ll have no more talk of it. The leetle fawn’s as welcome in this house as Jody. It’s hissen. We’ll raise it without grudgment o’ milk or meal. You got me to answer to, do I ever hear you quarrelin’ about it. This is Jody’s fawn jest like Julia’s my dog.”

Jody had never heard his father speak to her so sternly. The tone must hold familiarity for his mother, however, for she opened and shut her mouth and blinked her eyes.

She said, “I only said it was young.”

“All right. So it is.”

He closed his eyes.