“The best education of the world”

In each Maya city there were two wells: one for drinking water and the other as an oracle to throw the girls almost twenty meters below. When brought out at noon, if they had not died in the cold water they were asked: “What did the gods say to you?” The Maya girls got back at their babies by tying their feet and hands up. And they did something else. Artificial cranial deformation had been practiced since prehistory, with Greek physicians mentioning the practice in some towns. The Mayas placed boards at the sides of the newborn’s cranium to mold it, when it is still plastic, to form the egg-shaped heads that the archeologists have found. Furthermore, the parents also placed objects between their baby’s eyes to make them cross-eyed. Just as the elongated heads, this was a sign of beauty. (When Hernández de Córdova ventured in the Yucatán coast in 1517 he took with himself two cross-eyed Indians he thought could be useful as interpreters.) Once grown, the children had to sacrifice their own blood: the boys had to bleed their penises and the girls their tongues. Some Mayas even sacrificed their children by delivering them alive to the jaguars.

Without specifically referring to Mesoamerican childrearing, deMause has talked about what he calls “projective care.” During the fearful nemotemi, the five nefarious days for the Mexicans, parents did not allow their children sleep “so that they would not turn into rats.” Let us remember the psychodrama of the self-harmer girl in Ross’ paradigm and take one step forward. Let us imagine that, once married, she projected on her own child the self-hatred. Such “care” of not letting the children to sleep was, actually, a case of dissociation with the adult projecting onto the child the part of her self that she was taught to self-hate. Another example: In the world of the Mexica the first uttered words addressing the newborn told him that he was a captive. Just like the shrieks that made the chroniclers shudder, the midwife shouted since it was believed that childbirth was a combat and, by being born, the child a seized warrior. The newborn was swaddled and kindly told: “My son, so loved, you shall know and comprehend that your home is not here. Your office is giving the sun the blood of the enemies to drink.” The creature has barely come to the world and it already has enemies. The newborn is not born with rights but with duties: he is not told that he will be cared for, but that he is destined to feed the great heavenly body. (DeMause has written about this inversion of the parental-filial roles in his studies about western babies in more recent centuries.) In the Mexica admonition the shadow of infanticide by negligence is also cast. “We do not know if you will live much,” the newborn was told in another exhortation.

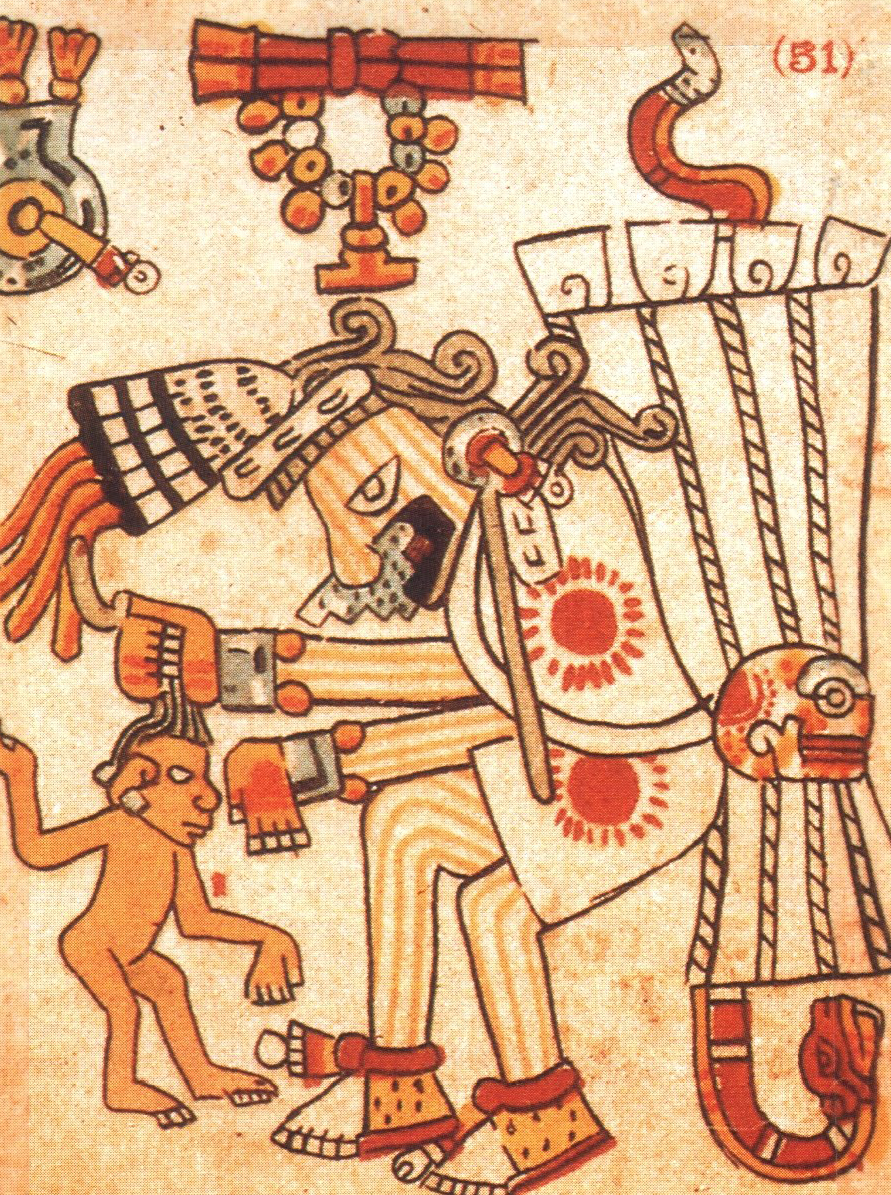

Tlazolteotl, goddess of infancy, grabbing a child by the hair.

Tlazolteotl, goddess of infancy, grabbing a child by the hair.

In the illustration can be noted the similarity of Tlazolteotl with the image of the warrior and his captive in the previous chapter. Just like that image, the goddess grabs the hair as a symbol of dominion. One of the few true things that Elsié Méndez told me, a woman so much criticized in my previous book, were certain words she pronounced that I remember verbatim: “La mamá lo pepena” [The mom grabs him] referring to those mothers of our times that choose one of their children to control him to the point of psychic strangulation.

In May of 1998 I listened in Mexican television Miguel León Portilla, the best-known indigenista scholar in Mexico, saying that the Mexica education was “the best education of the world.” Almost a decade later I purchased a copy of the Huehuetlatolli that León-Portilla commented, which includes one page in Nahuatl. The Huehuetlatolli were the moralizing homilies in the first years of the children: ubiquitous advices in Nahua pedagogy. They were not taught in the temples but from the parents to their children, even among the most humble workers, within the privacy of the home. In the words of León-Portilla: “Fathers and mothers, male teachers and female teachers, to educate their children and pupils they transmitted these messages of wisdom.” The exordiums were done in an elegant and educated language, the model of expression that would be used at school. A passage from the Huehuetlatolli of a father to his son that Andrés de Olmos transcribed to Spanish says:

We are still here—we, your parents—who have put you here to suffer, because with this the world is preserved.

This absolute gem depicts in a couple of lines the Mexica education. Paying no attention to these kind of words, on the next page León-Portilla comments: “Words speak now very high of its [the Mexica’s] moral and intellectual level.” Later, in the splendid edition of the Huehuetlatolli that I possess, commented by the indigenista, the sermon says: “Do not make of your heart your father, your mother.”

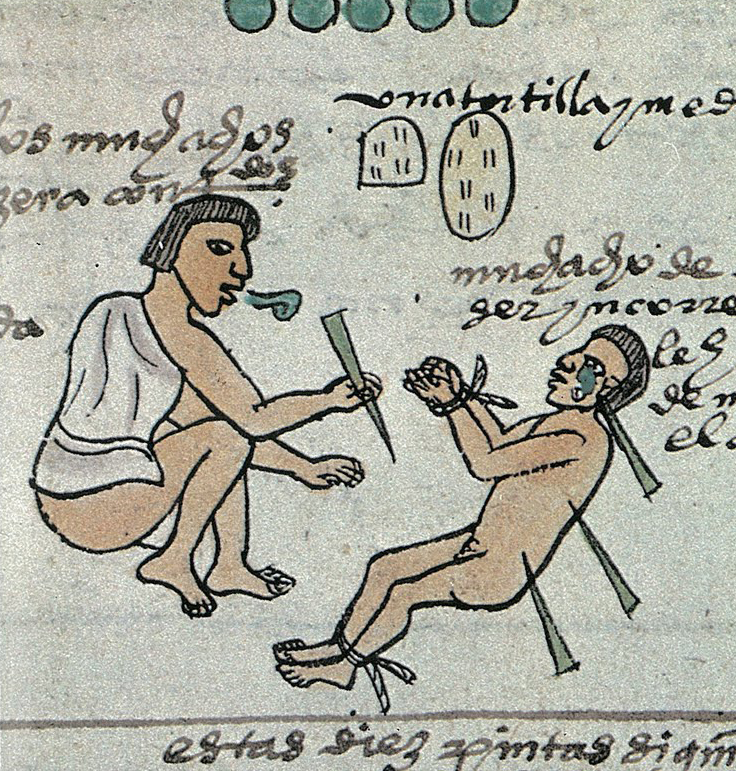

This advice is the perfect antithesis to Pindar’s “Become what you are!” which summarizes the infinitely more advanced Greek culture of two thousand years before. While León-Portilla describes the Nahua exordiums as highly wise and moral, they actually represent a typical case of poisonous pedagogy [a term explained in my previous book]. If there is something clear after reading the Huehuetlatolli is that that education produced no individuals whatsoever: other people lived the lives of the children, adolescents and youths who are exhorted interminably. What is worse: while León-Portilla praised the education of the ancient Mexicans on national television, at the same time the program displayed codex images depicting pubescent children tied up on their wrists and ankles, with thorns sank into their bodies and tears on their faces. The indigenista had omitted to say that “the punishments rain over the child” as Jacques Soustelle wrote in Daily Life of the Aztecs. The Mexica parents scratched their children with maguey thorns. They also burned red chili peppers and placed their child over the acrid smoke.

Codex Mendoza, page 60: Punishes to children ages 11 to 14.

Note the tears of the child and the sign of admonition

near the father’s mouth.

Another punishment mentioned in the codex was the beating of the child with sticks. Motolinía, Juan de Torquemada, Durán and Sahagún corroborated that the education was fairly severe. It is germane to note that in the mode of childrearing that deMause calls “intrusive,” the striking with objects is considered more prejudicial for the self-image of the child than the spanking of the psychoclass he calls “socializing.” It is also important to note that the parents were the ones who physically abused the children. It is true that the language of the Huehuetlatolli is very sweet: “Oh my little daughter of mine, little dove! These words I have spoken so that you may make efforts to…” But in the first book of this series I demonstrated the short circuit that produces in a child’s mentality this sort of “Jekyll-Hyde” alternation in the parental dynamics with their child.

The Mexicas copied from the Mayas the custom of selling their children. The sold out children had to work hard or they would be punished. A poor family could sell their child as a slave to get out from a financial problem. This still happened in the times when the Spaniards arrived. The noble that stole his father could be punished with death, and it is worth saying that the great draughts of 1450-1454 were dealt with the massive sacrifice of children to the water deities.

Which was the attitude that the child had to had toward such parents? In Nahuatl the suffix -tzin was aggregated to the persons that would be honored. Totatzin is our respected father. In previous pages I noted that the frenetic dances discharged the affects contained in the Mexica psyche. Taking into account that in such education the child was not allowed to live his or her feelings—as it is clearly inferred from the texts cited by León-Portilla (not only the Huehuetlatolli but educational texts in general)—, the silhouette of what had to be discharged starts to be outlined.

In Izcalli, the last month of the Mexica calendar, the children were punctured on the ears and the blood was thrown to the fire. As I said, at ten the boy’s hair was cut leaving a lock that would not be cut until, already grown, he would take a prisoner. In one way or the other every Mexica male had to participate in the seizure of victims for the serial killing. Those who could not make prisoners had to renounce the military theocracy and resign themselves with being macehuallis: workers or plebeians attached to their fields who, under the penalty of death, were forbidden to usurp the honorific symbols of feathers, boarded dresses and jewels. The macehuallis formed the bulk of the society. On the other hand, he who captured four prisoners arrived with a single jump at the upper layer of society. To excel in the seizure of men for the serial killing was so relevant that “he who was born noble could die slave.”

Both on national television and in his writings, León-Portilla is filled with pride that the ancient Mexicans were the only peoples in the world that counted with obligatory schooling in the 16th century. The indigenista belongs to the generation of my father, when children’s rights were unheard as a subject, let alone parental abuse. The form in which the Nahuas treated their children, that presently would be considered abusive, was continued at school. The school education to harden the soul of the elite, the Calmécac (“house of tears”) consisted of penances and self-harming with maguey thorns. Another case of the father’s projective care was the advice to his son about the ultra-Spartan education he would be exposed in the boarding school:

Look, son: you have to be humble and looked down on and downhearted […], you shall take out blood from your body with the maguey thorn, and take night baths even though it is too cold […]. Don’t take it as a burden, grin and bear it the fasting and the penance.

“Don’t take it as a burden” means do not feel your feelings. According to Motolinía, this most beloved practice of homiletic admonitions was even longer for the girls. In the boarding school the boy had to abandon the bed to take a bath in the cold water of the lake or a fountain. As young as seven-year-olds were encouraged to break from the affective attachment at home: “And don’t think, son, inside of you ‘my mother and my father live’. Don’t remember any of these things.”

Because the child was consecrated for war since birth, the education at schools was basically military. The strictly hierarchical system promised the striving young to escalate to the level of tequiuaque and even higher if possible. If the boy of upper classes did not want to become a warrior he had another option: priesthood. About his twentieth year he had to make a choice: a military life or a celibate and austere life, starting with playing the drum or helping the priest with the sacrifices. Severity was extreme: one of Netzahualcoyotl’s laws punished by death the drunk or lusty priest. No society, not even the Islamic, has been so severe with adultery and alcoholism: crimes where the capital punishment was applied both for the male and the female. The macehuallis who got drunk were killed in front of the adolescents. (The equivalent today would be that American schoolchildren were required to witness the executions of the pot addicts in the electric chair, as a warning.) The Calmécac were both schools and monasteries ruled by priests in black clothes. In the Florentine Codex an image can be seen of adolescents wearing dresses made of fresh human skins. We can imagine the emotional after-effects that such practice, fostered by the adult world, caused in the boys.

In the Nahua world it was frowned upon that the youth expressed his grudges and it was considered acceptable that he restrained and controlled himself. No insolent individual, Soustelle tells us, “no one who talked what came to his mouth was placed in the real throne,” and the elite were the first ones to submit to the phlegmatic code. And it was not merely a matter of concealing the grudges when, say, a boy or a girl learnt that their own parents had offered a little sister as sacrificial payment. The parents advised them in the ubiquitous sermons: “Look that your humility not be feigned, because then it will be told of you titoloxochton, which means hypocrite.” In the Nahua world the child was manipulated through the combination of sweet and kind expressions with the most heinous adultism. The parents continued to sermon all of them, even “the experienced, the fully grown youth.”

An unquenchable sun

Tell me who are your gods and I will tell you who you are. The myth of the earth-goddess Tlaltecuhtli, who cried because she wanted to eat human hearts, cannot be more symbolic. Just as the father-sun would not move without sacrifices, the mother-earth would not give fruits if she was not irrigated with blood. Closely related to Tlaltecuhtli, Coatlicue, was also the goddess of the great destruction that devours everything living.

Sacrifices were performed in front of her; vicious rumors circulated around about “juicy babies” for the insatiable devourer. In the houses the common people always had an altar with figurines of a deity, generally the Coatlicue. (In our western mind one would expect to find the male god of the ancient Mexicans, Huitzilopochtli.) The terrible goddess demanded:

And the payment of your chests and your hearts would be that you will be conquering, you will be attacking and devastating all macehuallis, the villagers that are over there, in all places through which you pass. And to your war prisoners, which you will make captives, you will open their chest on a sacrificial stone, with the flint of an obsidian knife. And you will do offerings of their hearts and will eat their flesh without salt; only very little of it in the pot where the corn is cooked.

Of the Mexica I only have a few culinary roots, such as eating tortillas. Culturally speaking, the educated middle and high classes in Latin America are basically European, of the type of Spain or Portugal. If we compare the above passage with our authentic roots, say, the Christianized exordiums of Numbers or Leviticus against cannibalism and other practices, the difference cannot be greater. Likewise, the Mexica mythology cannot contrast more with the superior psychoclass of Greece: where Zeus opens the belly of his father, Cronus, who had swallowed his siblings establishing thus a new order in the cosmos.

The papas punctured their limbs as an act of penance for the gods. These gods were a split-off, dissociated or internalized images of the parents. Even the emperor frequently abandoned the bed at midnight to offer his blood with praying. The Anonymous Conqueror was amazed by the fact that, among all of the Earth’s creatures, the Americans were the most devoted to their religion; so much so that the common Indian offered himself by taking out blood from his body to offer it to the statues. The 16th century chronicler tells us that on the roads there were many shrines where the travelers poured their blood. If we remember the scene of the Mexican film El Apando, based on the homonym book by José Revueltas where a convicted offender in the Lecumberri penitentiary bled himself while the other prisoners told him that he was crazy, we can imagine the leap in psychogenesis. What was considered normal in the highest and most refined strata of the Mesoamerican world is abnormal even in the snake pits of modern Mexico. The most terrible form of Mexica self-harming that I have seen in the codexes appears on page 10 of the Codex Borgia: a youth pulling out his eye as symbol of penitence. This was like taking the disturbing Colin Ross paradigm about the little girl to its ultimate expression.

At the bottom of the Mesoamerican worldview it always appears the notion that the creature owes his life, and everything that exists, to his creators: paradigm of the blackest of pedagogies that we can imagine. [Schwarze Pädagogik, literally black pedagogy, is a term popularized by Alice Miller. English publishing houses translate it as “poisonous pedagogy.”] The Mesoamerican mythology speaks of the transgression of some gods to create life without their parents’ permission, thus making themselves equals with them. In the Maya texts it is said that these children “made themselves haughty” and that what they did was “against the will of the father and the mother.” The transgressors were expelled from heaven and to come back they had to sacrifice themselves. Two of them threw themselves alive into the bonfire and were welcomed by their pleased parents. The resonances of this myth appear in the practice of throwing the captives to the bonfire. We should remember Baudez’s analysis: Mesoamerican sacrifice replaces self-sacrifice. It is merely a substitute sacrifice “as it is shown in the first place by the primeval myths that precede self-sacrifice.” This original sin condemned human beings to the sacrificial institution since “they could not recognize their creators.” (When I reached this passage in Arqueología Mexicana I could not fail but remember my father’s phrase that injured me so badly, as recounted in my previous book, when he referred to the damned “because they didn’t recognize their Creator.”) The sacrificial institution thus understood was a score settling, a vendetta. Moreover, in some versions of the Mesoamerican cosmogony the sun gives weapons to the siblings faithful to their parents to kill the 400 unfaithful children. The faithful execute the bidding and thus feed their demanding parents: once more, the cultural antithesis of the successful rebellion by Zeus, who had rescued their siblings from the tyrannical parent.

The connection of childrearing with the sacrificial institution is so obvious that when the warrior made a captive he had it as his son—which explains why he could not participate in the post-sacrificial feast—and the captive had him as his lord father. Some historians even talk about dialogues. When making a prisoner, the capturer said: “Behold my beloved son,” and the prisoner responded: “Behold my honored father.” In one of the water holydays of the Tota forest, which means “Our Father,” a girl was taken beside the highest tree to be sacrificed. Each time that the priest lifted a heart toward the sky as a sun offering the catastrophe that threatens the universe was, once more, postponed because “without the red and warm elixir of the sacrificed victims the universe was doomed to freeze.” As modern schizophrenics reason, the universe of the common Mesoamerican, just as the bicameral minds of other cultures, was constantly threatened and exposed to a catastrophe. The primordial function of the human race was to feed their parents, intonan intota Tlaltecuhtli Tonatiuh, “to our mother and our father, the earth and the sun.” The elegance of these four Nahua words evokes the compact Latin.

In the Mexica world destiny was predetermined by the tonalpohualli, “the count of the days” of the calendar where an individual’s birth by astrological sign was his fate. If León-Portilla had in mind the pre-Columbian cultures, he erred in his article “Identidad y crisis” published in July of 2008 in Reforma, by concluding that in antiquity the sun was seen as the “provider of life.” Duverger makes the keen observation that the solar deity, which appears at the center of the calendar, was so distant that it was not even worshipped directly. Instead of providing life the insatiable deity demanded energy, under the penalty of freezing the world (“We are still here—we, your parents—who have put you here to suffer, because with this the world is preserved”). The noonday heavenly body is not a provider of energy: it demands it. The thirsty tongue that appears at the very center of the Stone of the Sun (also called Aztec Calendar) looks like a dagger: it represents the knife used during the sacrifices. The solar calendar with Tonatiuh at the center of the cosmos was an absolute destiny: he could not even be implored. It is important to mention the psychohistorical studies about the diverse deities of the most archaic form of infanticidal cultures: according to deMause, they were all too remote to be approached.

When I think of the musician that sacrificed himself voluntarily to Tezcatlipoca in the holyday of the month Tóxcatl, which according to Sahagún was a holiday as sacred to the Mexicas as Easter to Christians, I see the culture of the ancient Mexicans under all of its sun. (Pedro de Alvarado would perpetrate the massacre in the main temple when he feared he would be sacrificed after that holiday.) Baudez’s self-sacrificial observation deserves to be mentioned again. Like the martyr of Golgotha who had to drink from the calyx that deep down he wanted to take away from himself, only if the young Indian submitted voluntarily to the horrifying death he earned the inscrutable love of the father. This is identical to the most dissociated families in the Islamist world, as can be gathered from deMause’s article “If I blow myself up and become a martyr, I’ll finally be loved.” But unlike Alvarado and the conquerors’ metaphorical Easter (and even contemporary Islamists), the Mexicas literally killed their beloved one before decapitating him and showing off his head in the tzompantli.

Just as the mentality of the Ancient World’s most primitive cultures, in the Mesoamerican world, where the solar cycle reigned since the Mayas and perhaps before, “the sacrifice was performed to feed the parent with food (hearts) and drinking (blood).” I had said that the priests’ helpers gave the captive’s “father” a pumpkin full of warm blood of his “son.” With this blood he dampened the lips of the statues, the introjected and demanding “shadows” of their own parents, to feed them. The priests smeared their idols with fresh blood and, as Bernal Díaz told us, the principal shrines were soaked with stench scabs, including the pinnacle of the Great Teocalli.

In our times, the ones who belong to this psychoclass are those who show off their acts by smearing the walls with their victims’ blood: people who have suffered a much more regressive mode of childrearing than the average westerner. Richard Rhodes explains in Why they Kill that Lonnie Athens, the Darwin of postmodern criminology, discovered that those who commit violent crimes were horribly subjected to violence as children. One hundred percent of the criminals that Athens interviewed in the Iowa and California prisons had been brutalized in their tender years. Abby Stein has confirmed these findings (Journal of Psychohistory, 36,4, 320-27). It is worth saying that, due to the foundational taboo of the human mind, when in January of 2008 I edited the Wikipedia article “Criminology” it surprised me to find, in the section where I added mention to Athens, only the pseudoscientific biological theories about the etiology of the criminal mind.

An extreme case at the other side of the Atlantic was that of a serial killer of children, Jürgen Bartsch, analyzed by Alice Miller in For Your Own Good. Bartsch had been martyred at home in a far more horrific way than I was. Miller believes that Bartsch gloated over by seeing the panic-stricken looks in the children’s eyes; the children that he mutilated in order to see the martyred child that inhabited in Bartsch himself.

___________

The objective of the book is to present to the racialist community my philosophy of The Four Words on how to eliminate all unnecessary suffering. If life allows, next time I will reproduce here the section on the encounter of the Spaniards with the American natives. Those interested in obtaining a copy of Day of Wrath can request it: here.