– For the context of these translations click: here–

CHAPTER 2

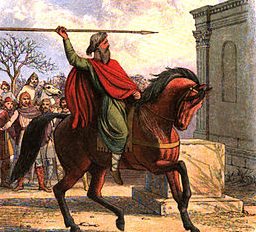

CLOVIS, FOUNDER OF THE GREAT FRANKISH EMPIRE

‘One of the most outstanding figures in universal history’. —Wilhelm von Glesebrecht, historian

‘And it is certain that he knew himself to be a Christian, and a Catholic Christian, something that is manifested over and over again in the various performances of his reign’. —Kurt Aland, theologian

The Rise of the Merovingians

The original land of the Franks, whose name was associated at the beginning of the Middle Ages with the concepts of ‘brave’, ‘audacious’ and ‘daring’, was in the Lower Rhine. These people, which lacked a unitary leadership, arose probably from the coalition of numerous small tribes throughout the 1st and 2nd centuries c.e., between the rivers Weser and Rhine. They are mentioned for the first time just after the first half of the 3rd century, when they fought fierce struggles against the Romans that would continue throughout the 4th and 5th centuries. The Franks settled on the right bank of the river and then breached the Roman line of defence of the Rhine, which some had probably already overcome before by infiltrating the border region. They advanced on Xanten, that the Roman population had evacuated towards 450, having occupied it later by the small Frankish tribe of Chatuarii. They then entered the territory between the Rhine and the Moselle; the Franks took Mainz and Cologne, a city that, on occupying it definitively around 460, became the centre of an independent Frankish state, immediately on the left bank of the great river. Little by little they annexed more territory. During the first half of the 5th century they conquered the city of Trier four times and the Romans recovered it as many times, until in 480 it became definitively owned by the Franks. The number of its inhabitants, from about 60,000 in the 4th century, dropped to a few thousand in the 6th century.

The invaders founded small Frankish principalities in Belgium and northern France, each subject to a kinglet or little king. As early as 480 the entire Rhenish region between Nijmegen and Mainz, the Maas territory around Maastricht, as well as the Moselle valley from Toul to Koblenz, belonged to the Frankish territory. The Romans allowed the Franks to settle on the condition that they rendered certain military services as foederati (allies) and they became their most loyal comrades in arms of all Germans, although they were generally torn apart amid fierce tribal strife. But in the end it was the Merovingians who bid for all of Roman Gaul…

King Childeric died in 482. Almost twelve hundred years later, in 1653, a doctor from Antwerp discovered his tomb at Tournai, endowed with such wealth and sumptuousness that it far surpassed the more than 40,000 tombs of the Merovingian period uncovered by archaeologists. At the death of Childeric in 482 he was succeeded by Clovis I (466-511), aged sixteen and apparently an only child. Allied with different sister tribes, Clovis expanded the Salic territory around Tournai, which was insignificant and reduced to a small part of northern Gaul in Belgium Secunda, though he continued the plunder, assassinations and wars, increasingly widespread over the regions from the Roman province to the left bank of the Rhine.

Such attacks reached first as far as the Seine, then as far as the Loire and finally as far as the Garonne, bringing the Gallo-Romans under the rule of the Franks. Even then, that was called ‘having the Franc as a friend, and not as a neighbour’.

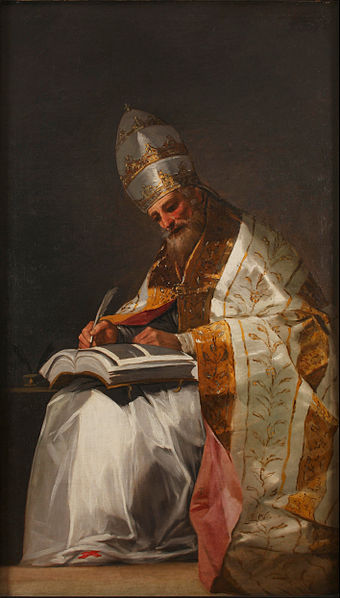

Such a bellicose people, over which the reputation of disloyalty also floated, was attractive to the Christian clergy from the beginning. The Arians, and even more so the Catholics, sought to win over their leader. In fact all the notable princes of that time in the West were Arian or heathen. Thus, as soon as Clovis was appointed King of Tournai, he was addressed by the Bishop of Reims, St. Remigius, a man of ‘eminent science’ and resurrector of the dead, according to the praise of Bishop Gregory who simultaneously highlights both traits…

A great bloodbath and the first date in the history of the German Church

Clovis soon passed from Soissons to Paris, which became the most important city and, at least since the 7th century, the true epicentre of the Frankish kingdom, in which almost all the Merovingian kings are also buried…

The Alemanni (or Suebi), first named in 213, had emigrated from the Elbe region and probably by the end of the 2nd century had made themselves strong in the Main region through various incorporations of German emigrants and soldiers. The name ‘Alemanni’ would mean what anyone who knows some German can still understand today: all males (alie Manner). The Alamanni, who were pressing on the Rhine and the line of fortifications on the frontier of the Roman Empire, broke in 406, accompanied in part by Vandals and Alans, dispersing through Gaul and Hispania.

When they tried to advance north-west from there, they clashed with the Franks, and in particular with the Francorans, who dominated the Moselle region. They had already allied with the Burgundians in 475 against the Alemanni, without clearly prevailing around 490 in a battle near Cologne, where the local kinglet Sigobert was wounded in one knee. Reason enough for Clovis to attack: in around 496-497 the Alaman king of unknown name died on the battlefield of Toibiacum. Clovis advanced into the German territory of the right bank of the Rhine and annihilated a good part of its still pagan inhabitants.

It is true that a decade later, around 506, they rose again; but again they suffered a bloody defeat, probably near Strasbourg, the Alaman king dying in battle again. Pursued by the Franks, they fled south to the pre-Alpine regions: Raetia Prima (province of Chur) and Raetia Secunda (province of Augsburg): territories under the influence of the Ostrogoth king Theodoric, who restrained his brother-in-law Clovis and who settled to the fugitives in Retia, Pannonia and northern Italy. But in the southern part of the Rhenish Hessen, in the Palatinate and the basins of the Main and Neckar the Alemanni were victims of the direct arrogance of Clovis. And from there the Franks later spread eastward to the Saale, the Upper Main and almost to the Bavarian Forest…

King Clovis had himself baptised in Reims with great pomp and with the assistance of numerous bishops. According to some, it ran annus 496-497, according to others 498-499; while according to some researchers, who put the war against the Alemanni in 506, we should think of the years 506-508. ‘It is the first date in the history of the German Church’ (Kawerau). Curiously, the event is linked to a great bloodbath and constitutes one of the most important events of the early Middle Ages.

The baptism of Clovis was a great feast. Streets and churches sparkled with their ornamentation. The baptismal church was filled with a ‘heavenly fragrance’, to the point that the attendees believed they were transferred ‘to the pleasant perfumes of paradise’.

Clovis was venerated as a saint in France.

Gregory of Tours refers that the king ‘advanced to the baptismal bath like a new Constantine’, and the comparison is terribly accurate, ‘to purify himself in the clean water of old leprosy and the dirty stains, which he had from ancient [pagan] times’. And Remigius, ‘the saint of God’, spoke to him with eloquent words: ‘Sigambrer, meekly bend your neck and worship what you burned and burn what you worshiped (adora quod incendisu, incende quod adorasli)’.

Who was this saint, who so arrogantly incited persecution, as did his colleague Avitus in his time? St. Remigius, like most of the prelates of that time (and not only of then), was of ‘illustrious’ lineage, and already at the age of twenty-two promoted to bishop of Reims. His older brother, Principius, was also bishop (of Soissons) and a saint too (their relics were to be burned by the Calvinists in 1567). Remigius, the apostle to the Franks, preached Catholicism to pagans and Arians with fervent zeal, something that clearly developed a ‘radical war’ (Schuitze), in which, according to a council of Lyon, ‘smashed the altars of idols everywhere and vigorously spread the true faith with many signs and miracles’…

Catholic Clovis made his own converts, pagans or Arians, so that the entire house of the Franks ended up being Catholic. Henceforth, a close ‘alliance between monarchy and episcopate’ (Fleckenstein) was created. The princes of the Church occupy the position of honour in the surroundings of Clovis and exert the maximum influence over him, especially Avitus and Remigius. And naturally the clergy are generously rewarded with the war spoils of the Merovingian. He rewards the prelates with largesse and splendour through foundations and donations of land… Since then ‘monarchy and church acted together for the further spread of Christianity’ (Schultze)…

From the research that we have today, it can well be argued that in reality the conversion of Clovis was a political, as that of Constantine had been before. Unlike the other Germanic peoples, the king and his people accepted Catholicism because it provided in advance a link between the conqueror and the Gallo-Romans who were subjected or who were to submit; linkage that did not occur in the rest of the Germanic kingdoms. Clovis, a sympathiser of the Church from an early age, became a Catholic to subdue the Arian Germanic tribes and win over neighbouring Gaul more easily with his strong majority of Roman Catholics…

Are we to free ourselves from a moralistic assessment of history?

After Clovis had won the war against the Visigoths with the help of the Francorans, between 509 and 511, the last years of his life, he achieved royal dignity over them. In any case, it forced the fusion of the Francorenan tribes with the Salian Franks.

He first instigated Chlodoric, son of King Sigobert of Cologne, to get rid of his father. ‘Look, your father has grown old and is limping with a crippled leg’. Sigobert ‘the Lame’, a former companion of Clovis, had limped since the battle of Toibiacum against the Alemanni, in which he had been wounded. At the hands of a hired assassin the prince eliminated his father in the beech forest. Through a delegation, Clovis congratulated the parricide and through it, he crushed his skull. The German historian Ewig describes all this with an elegant expression, too elegant we would say, of ‘diplomacy of intrigues’. After the double act, Clovis went to Cologne, the residential city of Sigobert, solemnly proclaimed his innocence in both crimes and, joyfully welcomed by the people, seized the ‘kingdom and the treasures of Sigobert’ (Gregory).

Then he fell on the Salian kings, with whom he was related. Such was the case, for example, of a Frankish king, Chararic, who had not once fought against Syagrius. With tricks Clovis seized him and his son. Later he locked them up in a monastery, had their hair cut off (the tonsure was a sign of the loss of royal dignity), forced Chararic to be ordained a priest and his son a deacon, and after having them beheaded he took over their treasures and kingdom.

Another relative, King Regnacar of Cambrai, his first cousin, was defeated by Clovis after having won over his entourage with a great amount of gold, which later turned out to be fake. After the battle, he mocked Regnacar, who was led into his presence in chains and who in 486 had helped him in the war against Syagrius: ‘Why have you humiliated our blood to that point and allowed yourself to be put in chains? You’d be better off dead!’ And he smashed his head off with an ax. They had also arrested Richar, the king’s brother: ‘If you had helped your brother, we would not have taken him prisoner’, Clovis rebuked him and killed him with another blow. ‘The named kings were close blood relatives of Clovis’ (Gregory of Tours). He also had their brother, Rignomer, liquidated in the vicinity of Le Mans. ‘Clovis thus strengthened his position throughout the Frankish territory’, to quote again the historian Ewig, thus summarising the existing situation.

The victims of Clovis’ consolidation of power throughout the Frankish territory were, it seems, several dozen Frankish cantonal princes. The tyrant had them murdered, seized their land and wealth, without ceasing to complain that he was alone:

‘Woe to me, now I find myself as a stranger among strangers and none of my relatives could help me, if calamity befalls me!’ But this was not meant because he was sorry for their death, but by cunning, in case perhaps there was still someone he could kill.

Such is the comment of St. Gregory, for whom Clovis was a ‘new Constantine’, and who embodied ‘his ideal of the ruler’ (Bodmer) and to whom he frequently appeared ‘almost like a saint’ (Fischer). Without shame the famous bishop adds:

But day after day God brought down his enemies before him and he increased his kingdom, because he walked with a right heart in His presence and did what was pleasing to His divine eyes.

This, as the context shows, also applies to Clovis’ murders of relatives. All is holy in the extreme, even the extreme crimes!

Such, then, was the primus rex francorum (Salic law), the king who ruled following to the letter the words of St. Remigius at his baptism: ‘Worship what you burned and burn what you worshiped’. Such was the Catholic king, that no longer tolerated any pagan vestige, although he commanded almost like an absolute tyrant and was bursting with hypertrophic brutality and rapacity, showing himself cautious and cowardly in front of the strongest and mercilessly crushing the weakest; the king who did not back down from any treachery and cruelty, who waged all his wars in the name of the Christian and Catholic God; the king who, with a sovereign power like few others and at the same time as a good Catholic, combined war, murder and religious piety, who ‘began his Christian reign with all premeditation on December 25’, who with his booty built churches everywhere, then he splendidly endowed and prayed in them, who was a great devotee of St. Martin, who carried out his ‘wars of the heretics’ against the Arians of Gaul ‘under the sign of an intense veneration of St. Peter’ (K. Hauck), and whom the bishops at the National Council of Orleans (511) exalted as ‘a truly priestly soul’ (Daniel-Rops).

That was Clovis. A man who, hearing the passion of Jesus, seems to have said that had he been there with his Franks, no such injustice would have been committed against the Lord. In the words of the old chronicler, he was as ‘an authentic Christian’ (christianum se verum esse adfirmat—Fredegar). And as the current theologian Aland also says: ‘And it is certain, and again and again he manifests it in the different performances of his reign, that he felt of himself as a Christian, and certainly a Catholic Christian’. In a word, that man who made his way ‘with the ax’ to climb the absolute rule of the Franks—as Angenendt graphically puts it—was no longer simply a military king, but thanks precisely to his alliance with the Catholic Church became the ‘representative of God on earth’ (Wolf). A man who, in the company of his wife St. Clotilde, finally found his last resting place in the Parisian Church of the Apostles, which was later called Sainte Geneviéve, when he died in the year 511, just turning forty: a great criminal, devious and ruthless, who established himself on the throne and, according to the historian Bosi, ‘a barbarian, who civilised and cultivated’.

The theologian Aland qualifies Clovis as akin to Constantine and euphemistically says that both were men of power, violent sovereigns and believes that justifiably: ‘Such rough times could only be controlled by such men’. But is it tough times that make tough men? Or is it not rather the other way around? One and the other are intimately united. And already St. Augustine had corrected the stupid accusation of the times: ‘We are the times; which are we, that’s the way the times are’. Aland wants to leave open the question of whether Constantine and Clovis were Christians:

Because both the sons of Constantine and Theodosius were rulers, of whose Christian confession there can be no doubt, and yet committed perfectly comparable acts of blood. If we want to understand them, we must free ourselves from such a moral assessment of history. Well, who among us whose people have a history of 1,500 years behind under the sign of Christianity, can say that he is Christian? Luther speaks of Christianity, which is always being made and which is never finished.

The Merovingian chroniclers glorify Clovis mainly for two reasons: for his baptism and his many wars. He became a Catholic demolishing and depredating everything around him he could destroy or prey. And thus, from an insignificant territorial principality, he created a powerful German-Catholic imperium, sealed in France the alliance between the throne and the altar, and became the chosen instrument of God who day after day struck down his enemies before him— :

because before God he walked with an upright heart, doing what was pleasing to His eyes.

—according to the enthusiastic praise of the bishop, St. Gregory.

As long as history is viewed in this way, as long as it remains outside of its ‘moral’ valuation and the vast majority of historians continue to crawl before such hypertrophic beasts of universal history with respect, reverence and admiration… history will continue to unfold as it does.