Below, an abridged translation from the third volume of

Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums.

The ‘Holy Scriptures’ are piled up

No evangelist intended to write a kind of revelation document, a canonical book. No one felt inspired, neither did Paul, and in fact none of the authors of the New Testament. Only the Book of Revelation: the one that, with difficulty, became part of the Bible pretends that God dictated the text to the author. But in 140 Bishop Papias did not consider the Gospels as ‘Holy Scriptures’ and gave preference to oral tradition. Even St. Justin, the greatest apologist of the 2nd century, sees in the Gospels—which he hardly quotes while he never ceases to mention the Old Testament—only ‘curiosities’.

The first to speak about an inspiration of the New Testament, which designates the Gospels and the epistles of Paul as ‘holy word of God’, was the bishop Theophilus of Antioch at the end of the 2nd century: a special luminary of the Church. On the other hand, in spite of the sanctity and divinity that he presupposes about the Gospels, he wrote a piece of apologetics about the ‘harmony of the Gospels’, as they were evidently a little too inharmonious.

Until the second half of the 2nd century the authority of the Gospels was not gradually accepted yet. Still, by the end of that same century the Gospel of Luke was accepted with reluctance; and that of John with was accepted with a remarkable resistance. Is it not odd that proto-Christianity did not speak of the gospels in the plural but in singular, the Gospel? In any case, throughout the 2nd century a fixed canon ‘of the Gospels did not yet exist and most of them were really considered a problem’ (Schneemelcher). This is clearly demonstrated by two famous initiatives of that time which tried to solve the problem of the plurality of Gospels with a reduction.

In the first place, there is the widespread Marcion Bible. This ‘heretic’, an important figure in the history of the Church, compiled the first New Testament in Sacred Scripture, and was the founder of the criticism of its texts, written shortly after the year 140. With it Marcion completely distanced himself from the bloodthirsty Old Testament, and only accepted the Gospel of Luke (without the totally legendary story of childhood) and the epistles of Paul; although, significantly, the latter without the forged pastoral letters and the epistle to the Hebrews, also manipulated. Moreover, Marcion deprived the remaining epistles of the ‘Judaistic’ additions, and his action was the decisive motive for the Catholic Church to initiate a compilation of the canon; thus beginning to constitute itself as a Church.

The second initiative, to a certain extent comparable, was the Diatessaron of Tatian. This disciple of St. Justin in Rome solved the problem of the plurality of the Gospels in a different way, although also reducing them. He wrote (as Theophilus) a ‘harmony of the Gospels’, adding freely in the chronological framework of the fourth Gospel the three synoptic accounts, as well as all kinds of ‘apocryphal’ stories. It had great success and the Syrian Church used it as Sacred Scripture until the 5th century. The Christians of the 1st century and to a large extent also those of the next century did not, therefore, possess any New Testament. As normative texts they used, until the beginning of the 2nd century, the epistles of Paul; but the Gospels were still not cited as ‘Scripture’ in religious services until the middle of that century.

The true Sacred Scripture of those early Christians was the sacred book of the Jews. Still in the year 160, St. Justin, in the broadest Christian treatise up to that date, almost exclusively referred to the Old Testament. The name of the New Testament (in Greek he kaine diatheke, ‘the new covenant’, translated for the first time by Tertullian as Novum Testamentum) appears in the year 192. However, at this time the limits of this New Testament were not yet well established and the Christians were discussing this throughout the 3rd and part of the 4th century, rejecting the compilations that others recognised as genuine. ‘Everywhere there are contrasts and contradictions’, writes the theologian Carl Schneider. ‘Some say: “what is read in all the churches” is valid. Others maintain: “what comes from the apostles” and third parties distinguish between sympathetic and non-sympathetic doctrinal content’.

Although around 200 there is in the Church, as Sacred Scripture, a New Testament next to the Old—being the central core the previous New Testament of the ‘heretic’ Marcion, the Gospels and the epistles of Paul—, there were still under discussion the Acts of the Apostles, the Book of Revelation and the ‘Catholic Epistles’. In the New Testament of St. Irenaeus, the most important theologian of the 2nd century, the book Shepherd of Hermas also appears which today does not belong to the New Testament; but the Epistle to the Hebrews, which does belong in today’s collection, is missing.

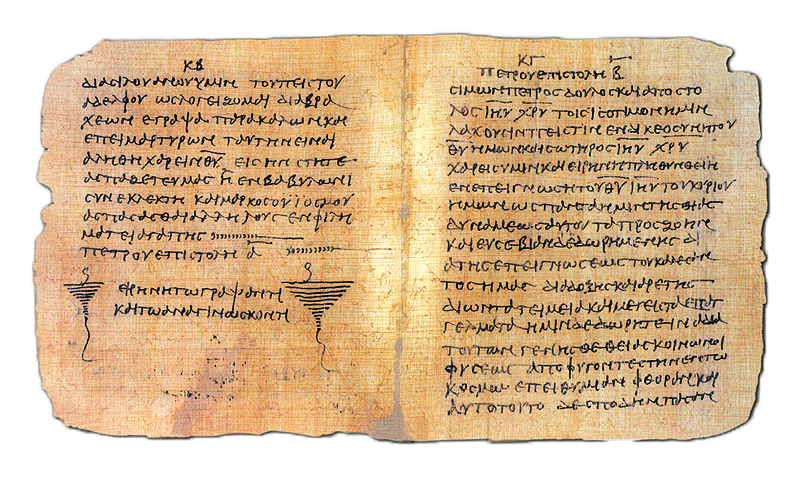

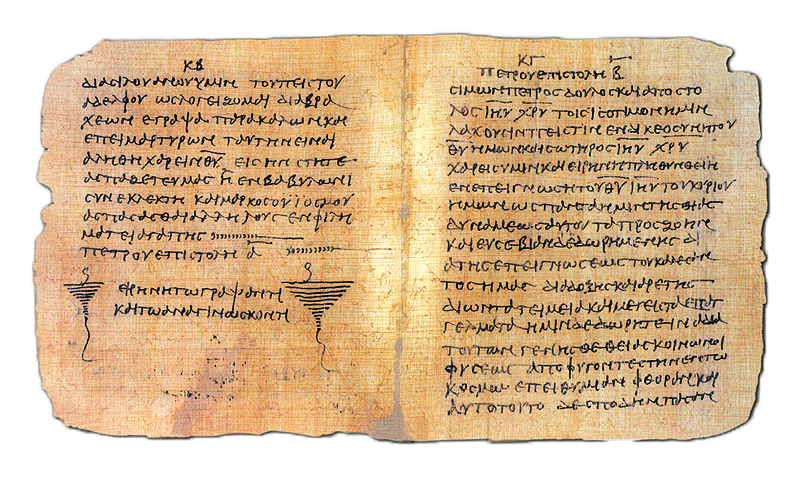

The religious writer Clemente of Alexandria (died about 215), included in several martyrologies among the saints of December 4, barely knows a collection of books of the New Testament moderately delimited. But even the Roman Church itself does not include around the year 200, in the New Testament, the epistle to the Hebrews; nor the first and second epistles of Peter, nor the epistle of James and the third of John. And the oscillations in the evaluation of the different writings are, as shown by the papyri found with the texts of the New Testament, still very large during the 3rd century.

(Papyrus Bodmer VIII, at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, showing 1 and 2 Peter.)

(Papyrus Bodmer VIII, at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, showing 1 and 2 Peter.)

Even in the 4th century, Bishop Eusebius, historian of the Church, includes among the writings that are the subject of discussion the epistles of James, of Judas, the second epistle of Peter and the so-called second and third epistles of John. Among the apocryphal writings, Eusebius accepts, ‘if you will’, the Revelation of John. (And almost towards the end of the 7th century, in 692, the Quinisext Council, approved in the Greek Church canons, appear compilations with and without John’s Book of Revelation.) For the North African Church, around the year 360, the epistle to the Hebrews, the epistles of James and Judas do not belong to the Sacred Scriptures; and according to other traditions, neither belonged the second of Peter and the second and third of John.

On the other hand, prominent Fathers of the Church included in their New Testament a whole series of Gospels, Acts of the Apostles and Epistles that the Church would later condemn as apocryphal but in the East, until the 4th century, they enjoyed great appreciation and were even considered as Sacred Scripture, among others, Shepherd of Hermas, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Didache, etc. And even in the 5th century it is possible to find in a codex some ‘apocryphal’ texts, that is, ‘false’ together with the ‘genuine’ ones.

The so-called Catholic epistles needed the most time to enter the New Testament as the group of the seven epistles. The Father of the Church St. Athanasius, the ‘father of scientific theology’ was the first one to determine its extension (whom the investigators also blame for the falsification of documents, collecting the 27 known writings, among them the 21 epistles). St. Athanasius lied without the slightest hesitation when affirming that the apostles and teachers of the apostolic era had already established the canon. Under the influence of Augustine, the West followed the resolution of Athanasius and consequently delimited, almost about the beginnings of the 5th century, the Catholic canon of the New Testament in the synods of Rome in 382, Hippo Regius in 393 and Carthage in 397 and 419.

The canon of the New Testament, used in Latin as a synonym for ‘Bible’, was created by imitating the sacred book of the Jews. The word canon, which in the New Testament appears only in four places, received in the Church the meaning of ‘norm, the scale of valuation’. It was considered canonical what was recognised as part of this norm, and after the definitive closure of the whole New Testament work, the word ‘canonical’ meant as much as divine, infallible. The opposite meaning was received by the word ‘apocryphal’.

The canon of the Catholic Church had general validity until the Reformation. Luther then discussed the canonicity of the second epistle of Peter (‘which sometimes detracts a little from the apostolic spirit’), the letter of James (‘a little straw epistle’, ‘directed against St. Paul’), the epistle to the Hebrews (‘perhaps a mixture of wood, straw and hay’) as well as the Book of Revelation (neither ‘apostolic nor prophetic’; ‘my spirit cannot be satisfied with the book’) and he admitted only what ‘Christ impelled’.

On the contrary, the Council of Trent, through the decree of April 8, 1546, clung to all the writings of the Catholic canon, since God was its auctor (author). In fact, the real auctor was the development and the election through the centuries of these writings along with the false affirmation of their apostolic origin.

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support this site.

Christians falsified more consciously than Jews

Christians falsified more consciously than Jews