Excerpted from the 17th article of William Pierce’s “Who We Are: a Series of Articles on the History of the White Race”:

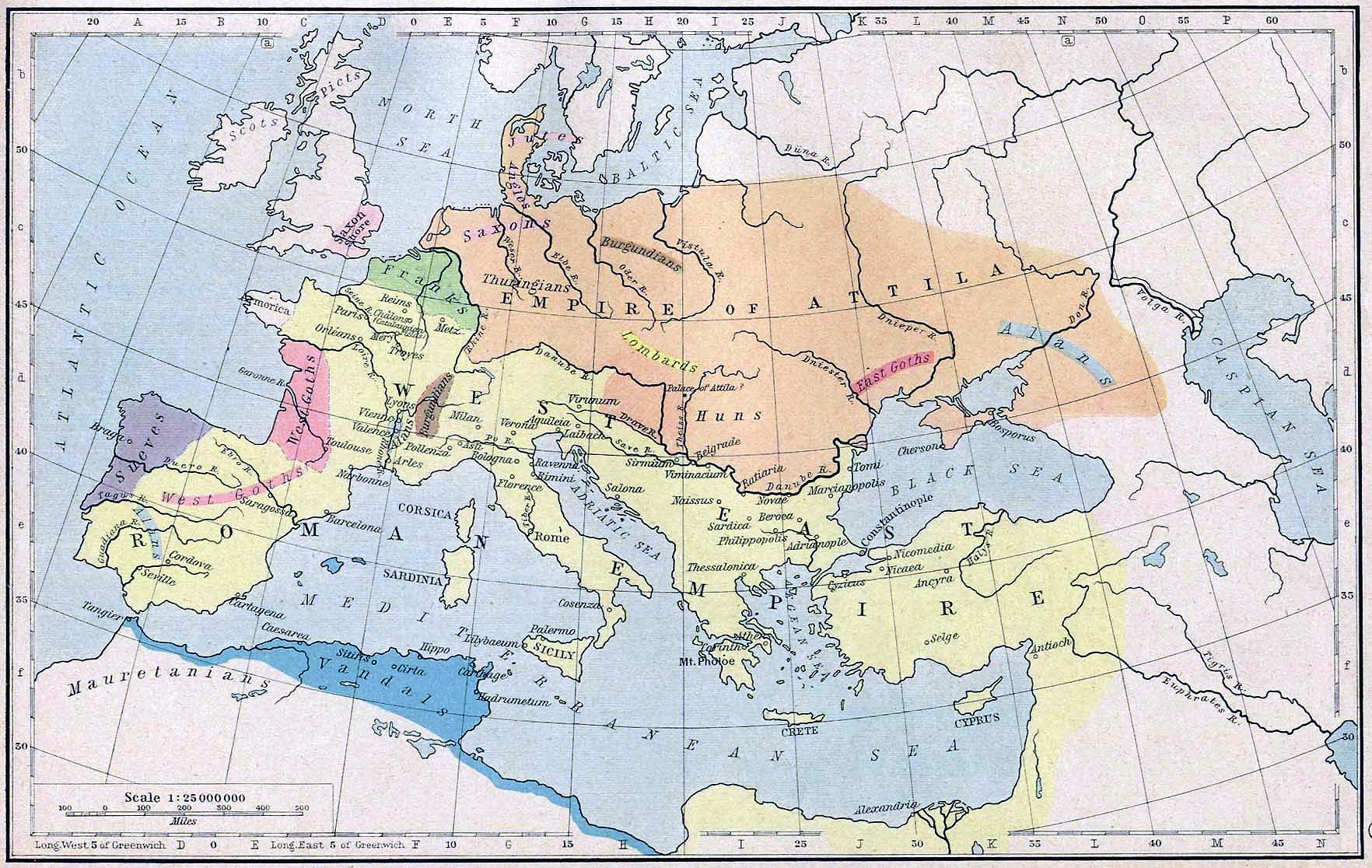

The Huns halted their westward push for more than 40 years while they consolidated their hold on all of central and eastern Europe, and on much of northern Europe as well. In 433 they gained a new king, whose name was Attila. In 445, when Attila established his new capital at Buda, in what is now Hungary, the empire of the Huns stretched from the Caspian Sea to the North Sea.

In 451 Attila began moving west again, with the intention of seizing Gaul and then the rest of the Western Empire. His army consisted not only of Huns but also of contingents from all the conquered peoples of Europe: Ostrogoths, Gepids, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, and others, including Slavs.

One contingent was made up of Burgundians, half of whom the Huns had subjugated (and nearly annihilated) in 436. The struggle between the Burgundians and the Huns forms the background for the German heroic epic, the Nibelungenlied.

Scourge of God

Attila’s mixed army threw western Europe into a state of terror as it advanced. So great was the devastation wrought on the countryside that Attila was given the nickname “the Scourge of God,” and it was said that grass never again grew where his horse had trod.

Two armies, one commanded by Aëtius, the last of the Western Empire’s Roman generals, and the other by Theodoric, King of the Visigoths, rode against Attila. Aëtius and Theodoric united their armies south of the Loire, in central Gaul, and compelled Attila to withdraw to the north-east.

Attila carefully chose the spot to halt his horde and make his stand. It was in a vast, open, and nearly level expanse of ground in northeastern France between the Marne and the Seine, where his cavalry would have ideal conditions for maneuvering. The region was known as the Catalaunian Plains, after the Catalauni, a Celtic people. The name of Chalons (ancient Catalaunum), is most often associated with the battle which took place on the Catalaunian Plains, although the actual site is much closer to the city of Troyes.

White Victory

In a furious, day-long battle frightful losses were inflicted on both sides, but the Visigoths, Franks, free Burgundians, and Alans of Aëtius and Theodoric had gained a decisive advantage over the Huns and their allies by nightfall. Attila retreated behind his wagons and in despair ordered a huge funeral pyre built for himself. He intended neither to be taken alive by his foes nor to have his corpse fall into their hands.

King Theodoric had fallen during the day’s fighting, and the command of the Visigothic army had passed to his son, Thorismund. The latter was eager to press his advantage and avenge his father’s death by annihilating the Hunnic horde.

Empire of Attila (orange) by 450 A.D.

The wily Roman Aëtius, however, putting the interests of his dying Empire first, persuaded Thorismund to allow Attila to withdraw his horde from Gaul. Aëtius was afraid that if Thorismund completely destroyed the power of the Huns, then the Visigoths would again be a menace to the Empire; he preferred that the Huns and the Visigoths keep one another in check.

Battle of the Nedao

Attila and his army ravaged the countryside again, as they made their way back to Hungary. The following year they invaded northern Italy and razed the city of Aquileia to the ground; those of its inhabitants who were not killed fled into the nearby marshes, later to found the city of Venice.

But in 453 Attila died. The 60-year-old Hun burst a blood vessel during his wedding-night exertions, following his marriage to a blonde German maiden, Hildico (called Kriernhild in the Nibelungenlied). The Huns had already been stripped of their aura of invincibility by Theodoric, and the death of their leader diminished them still further in the eyes of their German vassals.

The latter, under the leadership of Ardaric the Gepid, rose up in 454. At the battle of the Nedao River in that year it was strictly German against Hun, and the Germans won a total victory, completely destroying the power of the Huns in Europe.

Slavic Opportunity

The vanquished Huns fled eastward, settling finally around the shores of the Sea of Azov in a vastly diminished realm. They left behind them only their name, in Hungary. Unfortunately, they also left some of their genes in those parts of Europe they had overrun. But in 80 years they had turned Europe upside down. Entire regions were depopulated, and the old status quo had vanished.

This provided an opportunity for the Slavs to expand, and they took advantage of it, as mentioned earlier. Unfortunately for them—and for our entire race—the area into which the Slavs expanded corresponded largely to the area invaded repeatedly in later centuries by Asiatic hordes from the east, and the Slavic peoples suffered grievously. We will examine these Asiatic invasions in later installments.