“There are two Hitlers, the real one and the Hollywood one. I write about the real Hitler, that’s why there is police at my door.”

—–David Irving

Today I read “Putsch”, the tenth chapter of the book, and I liked that Himmler referred to Hitler as “the Messiah of the next thousand years”. Unfortunately, on this side of the Atlantic, except for George Lincoln Rockwell and his successors, no one sees the Führer in this way, which is why the American racial movement has strayed into a dead end.

Today I read “Putsch”, the tenth chapter of the book, and I liked that Himmler referred to Hitler as “the Messiah of the next thousand years”. Unfortunately, on this side of the Atlantic, except for George Lincoln Rockwell and his successors, no one sees the Führer in this way, which is why the American racial movement has strayed into a dead end.

A return to the NS of the last century won’t happen until the dollar collapses. In the same chapter, David Irving informs us that on 1 August 1923 it cost three million Reichsmarks to buy one American dollar. I cross my fingers that Trump’s erratic policy in Ukraine, Israel, Iran and even the Federal Reserve will lead to a situation where it will take three million hyperinflated dollars to buy one Russian rubble (insofar as Putin has plans to return to the gold standard after winning in Ukraine). Only in a humiliating situation analogous to this scenario could the “country-club conservatism”—Michael O’Meara’s term—that is WN begin to be repudiated.

In that ideal world, let’s take note of what Himmler wrote in four lines, as Irving informs us on page 129 of his book, during the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic:

Armed struggle – power.

Hitler.

Völkisch movement.

Grossdeutschland – Greater Germany.

On this side of the pond, Himmler’s words would mean not only the expulsion of non-whites from US territory, but also a Master Plan South equivalent to Himmler’s Master Plan East, which, had he been successful, would have prevented the Russians from becoming the world’s leading military power.

As I said, such a drastic change in values in the collective unconscious of Americans is inconceivable unless a catastrophe similar to, or even worse than, the hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic between 1921 and 1923 occurs. Irving informs us on page 133 that by November 1923 “to purchase one copy of the Völkischer Beobachter now cost eight thousand million marks… Priceless paintings were sold by families just to eat” (his italics).

When will the US enter into a convergence of catastrophes: a financial disaster followed by social unrest and real political change?

I exaggerated last Saturday when I said that David Irving’s True Himmler was only about Heinrich’s childhood and adolescence. I have read on and it has a few sentences worth quoting. If the senior figures of the Third Reich were heroes or saints for the ‘dissident’ right it would still be possible to save the Aryan from inexorable extinction. But they are not: many of them still have legendary Jews as their heroes!

Yesterday, for example, I was shocked to find that both Alexander Mercouris, who vlogs in his English channel (here), and three well-known Spanish ‘dissidents’ in the YouTube subculture (here), talked about Good Friday as if my very Christian father were still alive and educating the teenager I was half a century ago!

Just as white nationalists in general ignore Carrier’s critique of the NT regarding Romulus—a critique that could very well be used to validate Kevin MacDonald’s approach to subversive Jewry—, the so-called dissidents haven’t emerged from the bubble they introjected from their ancestors.

So back to Himmler, for although Heini received a strict Catholic upbringing as a child, as an adult he was able to transvalue his values. I think that on this point Maurice is right in saying that we need more Holocaust affirmers in the movement: something that couldn’t contrast more with the heavy chains with which Christian ethics, in both its traditional and neochristian versions, undermines the Aryan collective unconscious.

On page 72 of True Himmler Irving informs us that Heini disliked beer (I dislike it too). Two pages later we read: ‘Easter will be very nice and cheerful’, Heini wrote to his mother. In another letter, dated May 1921, Heini wrote to his mother that he had visited Salzburg by bicycle, where he went to church. At the age of twenty-one Himmler still felt at home with his pious parents and among the Catholic architecture of St Michael’s, the largest Renaissance church in the Alps. He particularly loved the royal Hofkirche for its ornaments and Old Testament frescoes: the church of All Saints where his cousin sometimes celebrated mass. Heini was such a good boy that he went to the eight o’clock mass one Sunday morning and wrote to his mother about his experiences in that church.

On page 90 we learn that Heini’s first contact with incipient National Socialism wasn’t with Hitler, but with the homosexual Ernst Röhm, who invited him to join the movement. However, Heini was always repulsed by such behaviour and didn’t join the movement—yet.

Adolf Hitler was older than Himmler, and at that time he was already saying things like: ‘We need a dictator who is a genius if we are to arise again’. I wonder how many white nationalists know that democracy is shit and that only a tough dictator could save them? Speaking in Salzburg, Hitler was already demanding the extirpation of the ‘Jewish bacillus’ from Austria and Germany (pages 93-94). ‘For us, this is not a problem to which you can turn a blind eye, one to be solved by minor concessions… Don’t be misled into thinking you can fight a disease without killing the carrier, without destroying the bacillus’. And on the same page of Irving’s book we can read:

‘We must be fired with a remorseless determination to grasp this evil at its roots and exterminate it, root and branch’. A few weeks later he repeated, ‘We cannot skirt around the Jewish Question. It has got to be solved’.

In 1923 hyperinflation hit Germany and only the Jews got richer having bought houses, land and works of art: which motivated the people to listen to radical voices, like Uncle Adolf’s. We can imagine why I believe that now the American dollar is the one that has to hyperinflate!

Just as many on the racial right deny the Holocaust, others deny that Hitler and Himmler wanted to conquer the lands of the half-gooks for the Aryans. On page 119 Irving again quotes Hitler:

Germany’s future lay in the east. ‘The destruction of the Russian empire and the distribution of its land and property, which will be settled by Germans…’

And on page 122 he does it again:

‘A solution of the Jewish Question is bound to come. If it can be resolved with common sense [the Madagascar Plan], so much the better’. If not, he predicted, there were two or more possibilities — ‘either the Armenian, Levantine, way or bloody confrontation’. In 1915 the Turks had brutally expelled the Armenians…

A few words later Irving ends the ninth chapter of True Himmler.

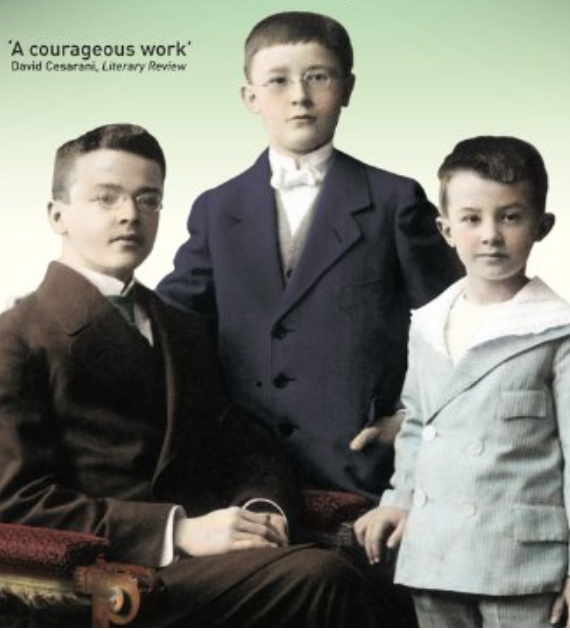

Early photo of Heinrich Himmler with his two brothers.

HUMBLED BY DEFEAT, RUINED BY REPARATIONS, the future for Germany looked bleak. A nameless gloom assailed Himmler, the military reservist. On November 7, 1919 he and Lou fetched helmets; he already had ‘the King’s tunic,’ as he called it, explaining, I’m a soldier and always will be.’ ‘Gebhard, Lou, and I talked some more,’ he wrote, ‘about how fine it would have been to go off to war together. Perhaps then I wouldn’t be here today – one fighting heart fewer… In a few years’ time I may yet go off to war and do battle. I’m looking forward to the war of liberation,’ he hinted, ‘and if there’s still a sound limb left on me I’ll be there.’ ‘Today,’ he wrote on December 1, 1919, ‘I’ve got a uniform on again. It’s the only suit I love to wear…’

Now nineteen, he began thinking of emigrating – to Russia. Back in Ingolstadt for a day, he talked it over with his parents. ‘There’s no place like home,’ he wrote. ‘Went for an evening stroll and a long chat – with Papa about Louisa, with Mama about the Russia thing mostly, and about the political and economic future. I prayed in the evening and was in bed by ten-thirty already.’ He missed his mother’s at-chocolate comforts: ‘It’s nice to be back home again,’ he wrote a few days before Christmas, ‘then you can be a child again.’

Louisa or Maja? ‘How happy could I be with either,’ John Gay had written in The Beggar’s Opera, ‘Were t’other dear charmer away.’ On the eve of St Nicholas, December 6, Heini found a mystery present, a gift hamper; from a blonde hair which his careful search discovered on it, he deduced that it was from Maja. On the way to the ice rink with Ludwig on the eighth, they talked about Maja, Kathe, and Gebhard, but at the ice rink Maja was downright obnoxious. The gift was from another blonde. ‘Just shows how stupid a man in love can be.’ He decided, ‘If l don’t find the girl who loves me, then I’ll head off to Russia alone. If Maja is still in love with me, then I’m glad for her because it’s great to love and be loved.’ A few days later, he summed up: ‘Maja is ignoring me. With her and Louisa I have learned one lesson: “There’s none so cruel as girls who have once loved you”.’

___________

David Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.

HE DID NOT UNDERSTAND WOMEN at all. After supper one evening he and Maja played the piano. ‘I think we see eye to eye. By God´s grace!’ He hurried home and worked some more on his Russian, a language he had started to learn. They held hands a lot that winter, or read books together, like the 1911 love story by Richard Voss, Zwei Menschen, Two People: the hero’s mother, a religious fanatic, dies of grief when he fails to take orders as a priest; guilt-stricken, he dumps his girl, whereupon she too kills herself, and he officiates at her funeral. Yes, women were odd creatures, and he spent a lot of his time feeling sorry for them. Maja performed more student chores for him, and he felt guilty about Louisa: ‘Over at four p.m. to the Hagers,’ he wrote: ‘I feel sorry for Louisa but there´s not much I can do. Perhaps this first big episode in her life will help her grow up.’ With Louisa he talked about everything under the sun, but then it was back to Maja. They kissed goodnight, and on Odeon Square afterwards a hooker caught up with him. ‘Obviously without scoring,’ he virtuously recorded. ‘But interesting all the same.’

With Maja, the girl with the flaxen hair, came the inevitable denouement. It was the last day of November 1919. ‘I don´t know if I´m imagining it, but Maja is not the same toward me as she used to be.’ He took her skating the next day. The ticket is still tucked into his diary today, together with five snapshots of a young girl.

___________

Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.

The above image appears in Irving’s book with this footnote: ‘Heinrich Himmler preserves the certificate recording his First Communion until the end.’

THE PLEASURES WHICH MADE those evenings ‘unforgettable’ also helped young Heinrich Himmler overcome his tendency to adolescent depression . ‘First of all Maja sang, “A Woman’s Love and Sorrow.” She sang the verses with tears in her eyes. I don’t think Ludwig understands her, his Golden girl, but I can’t be sure of that. I just don’t get him. Later Gebhard and Kathe played the piano.’ Kathe Loritz – also Maja – was Ludwig Zahler’s girl, and later his wife. ‘Ludwig and I shared an armchair. Marielle [Lacher] and Maja sat on the floor clinging to us both. We all cuddled, partly in love and partly in a fraternal embrace. It was an evening I won’t easily forget.’

He felt sorry for poor Maja, he wrote on November 5, 1919; and two days later there was more of the same: then he sermonized to a hidden congregation in his diary, ‘Yes, it’s true: Mankind is a wretched creature. Restless is the heart, until it rests with Thee, 0 Lord [see my comment in the comments section - Editor]. How powerless are we, we can’t help it. I can but be a friend to my friends, do my duty, work, struggle with myself, and never allow myself to lose control.’ After just a month living among educated youngsters like himself, he was beginning to question everything. Louisa no longer excited him. On Sunday morning he went to the cathedral for Mass and the sermon, and then over to her family, the Hagers: ‘Louisa was nice enough, but not the way I like.’ He spent a cheerful evening after that with Maja’s family. ‘Today I have by and large regained my spiritual balance. God will help me forwards.’

Thus as he plunged into the world of agriculture an inner turmoil began, between the strict religious doctrines impressed upon him by his parents, and the unfamiliar chemistry of student life and adolescence. ‘I work,’ he wrote on November 11, i919, ‘because it is my duty, because I find peace in work; and I work for my Germanic ideal of womanhood with whom I shall one day live my life and fight my battles as a German in the East, far from my beloved Germany.’ One evening a hypnotist came round to the Loritz household and tried his black art on them. ‘I summoned up all my powers of resistance,’ boasted Heini. ‘Obviously it did not work with me. But it did totally with poor little Maja. I felt so sorry for her when I saw her go under. I could have strangled the dog in cold blood. I worked against him where I could. . . His mind-reading was very good, but I think anybody capable of concentrating could do it with sufficient practice. I instinctively disliked the fellow, I hate this whole swindle; it only comes off if you go along with him.’

He loved Maja’s eagerness to help; she made a fair-copy in twenty pages of neat handwriting for him of his zoology paper, and repeated the drawings with great care. A day or two later he helped her with her math, and ‘she thanked me very much – (he drew a careful line, and did that again the next day). His heart in a whirl, zerwühlt, he wrote that Friday evening: ‘Then over to the Loritz’s for a meal. Maja was very nice – and there was the line again. (Those who research in private diaries know not to ignore such signs.)

He was still acquiring social graces. That included taking lessons in ballroom dancing, which he loathed as only a nineteen-year-old can. ‘Diary, November 15, 1919: From eight to ten at dancing-class.’ – and here he inserted three [iron] crosses. ‘All beginnings are hard,’ he added, using a German aphorism, ‘but I’ll get the hang of it. Dance classes seem pretty pointless to me, and just a waste of time.’ ‘What a disgusting fraud it all is,’ he commented. ‘But I’ll be glad once I’ve learned to do it, and I can dance with whoever takes my fancy.’ ‘If I could only look danger squarely in the eye,’ he added in one entry, ‘risk my life somewhere, fight, that would be a real liberation for me.’

___________

Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.

THERE WAS ONE OVERHANGING PROBLEM, the growing left-wing unrest in Bavaria. The army might soon have him doing night patrols as a reservist. ‘Dear Mother, Dear Father,’ he wrote on November 6, 1919. ‘Today you get your promised letter. Thanks a lot for your dear packages. The one with coat and fur jumpers arrived this morning. Gebhard collected the other at the post office this afternoon. Again, dear Mother, thanks a lot. After all, your boys are a bothersome pair. The possibility exists that they will call us up in a few days’ time…’

THERE WAS ONE OVERHANGING PROBLEM, the growing left-wing unrest in Bavaria. The army might soon have him doing night patrols as a reservist. ‘Dear Mother, Dear Father,’ he wrote on November 6, 1919. ‘Today you get your promised letter. Thanks a lot for your dear packages. The one with coat and fur jumpers arrived this morning. Gebhard collected the other at the post office this afternoon. Again, dear Mother, thanks a lot. After all, your boys are a bothersome pair. The possibility exists that they will call us up in a few days’ time…’

After adding a breakdown of their expenses, he asked for more cash. ‘Then Mother, we would like to for the following with our next laundry parcel (but there is absolutely no hurry): 1. smokes for Gebhard, 2. a little green cover for the travelling suitcase, 3. wax paper to wrap sandwiches, 4. Gebhard’s electric flashlight, 5….’ Such letters are hard to paraphrase, but they provide much we need to know about Heinrich Himmler at this time.

After his recovery from illness he went to confession twice: he found himself thinking impure thoughts about women. He had begun cautious friendships – primarily with Ludwig’s girl, Maja Loritz and also with Louisa Hager, the daughter of trusted family friends; her mother evidently approved, as the two females came round and joshed him. ‘Friendship? Love?’ pondered Himmler in his diary. ‘Another step towards maturity. But I will stay indifferent.’

‘Then over to the Hagers for lunch,’ he confided on October 20, 1919, the day he registered at the Polytechnic: ‘Mama Hager was as nice and kind to me as ever. Afterwards we talk about private dancing lessons.’ Louisa resorted to tears, every woman’s last resort. ‘Floods of tears from the poor thing. I felt really sorry for her. She does not realise how pretty she is when she cries. I escorted her to the streetcar, then went to the State Library and read up on the war of 1812. From four to five o’clock I sat in on a lecture at the Veterinary School.’ Louisa went to Communion every day, and she shot up in his esteem. ‘This really was the best thing I have heard this last week.’ Most evenings after lectures, which began on November 3, the four friends went to concerts or an indoor swimming pool. Heini found it difficult to juggle these two females, Maja and Louisa. With Maja he visited the theatre and talked about religion; he wrote rapturously, ‘I think I’ve found a sister.’ Less innocently perhaps, he was thrilled that she hooked her arm in his, as they went for a stroll with Gebhard and his girl. But Heini was plagued with irritation about Louisa – and twice he lamented in his pages, ‘She won’t let her hair down.’

___________

Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.

ON JUNE 26, 1919 Himmler’s father had become headmaster of the Gymnasium in Ingolstadt. For a few weeks Heini worked on a farm at Oberhaunstadt nearby. A work diary started on August 1 shows him toiling in stables, fields, and the dairy. On August 15 he entered, ‘Stables as usual. Church in the morning, with Mr Franz after lunch.’

On September 2 he fell ill with salmonella poisoning, and he remained bedridden for the rest of the month. On the twenty-fourth a doctor in Munich diagnosed an enlarged heart, and advised him to quit farm work for a year and concentrate on studies. Himmler transferred from rural Bavaria to Munich. He applied to study at the Polytechnic and paid the requisite fees. At the same time his brother Gebhard engaged to read mechanical engineering. The four storeyed building sat with its square, copper-sheathed clocktower between Gabelsberger Strasse and Theresien Strasse. The Polytechnic’s file records them as living just two blocks away from the college at No. 5, Schelling Strasse, a street much trodden later in history.

The Polytechnic issued a matriculation certificate on October 18, 1919. Heini would study here until 1922. He had chosen to read agriculture, and he might well have prospered as a farmer; farmers seldom go hungry. The two brothers would share digs, and take their weekly bath at the Luisenbad (at home they had only an old-fashioned bath contraption). ‘Our room looks very comfortable right now,’ he wrote to his parents a few days later. ‘I just wish you could see it. Everything excellently in its rightful place. In the mornings we drink tea, which is very good. We get up at six-thirty. Then we tot up our outgoings of the day before and reconcile them’ – this no doubt for their father’s benefit. ‘For the morning break we always buy cheese.’

His mother did the laundry for them both. The parents still required him to practise the piano, and he struggled with the keys until they conceded defeat. He went back to Ingolstadt frequently, and took Thilde their old nanny from Sendling, the Munich suburb where she lived, to the Waldfriedhof to see one grandmother’s grave and then a day later with Gebhard to the southern cemetery to visit their other’s.

Like freshers everywhere, Heini signed up for everything – the Polytechnic union, an old boys’ society, a breeding association, a gun club, the local Alpine society, and the officers’ association of the 11th Infantry Regiment. The return to Munich, his big native city, also brought Heini together with Mariele, the sister of Ludwig Zahler, a former comrade during his military training at Regensburg; Ludwig was Heini’s second cousin, and became his best friend at the Poly.

___________

David Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.

THE TIDE OF WAR receding across Europe had left behind ugly whirlpools; Bavaria was in permanent unrest. Communists, socialists, regular army, and Free Corps disputed control, always keenly watched by the central government in Berlin.

THE TIDE OF WAR receding across Europe had left behind ugly whirlpools; Bavaria was in permanent unrest. Communists, socialists, regular army, and Free Corps disputed control, always keenly watched by the central government in Berlin.

The example of Hungary had struck terror into Munich’s middle classes: in Budapest Bela Kun, a Transylvanian Communist (born Bela Cohn) seized power. In Munich, the turmoil continued after the killing of Kurt Eisner: a triumvirate of ‘Russian’ Jews under the St Petersburg-born Communist Evgenii Levine, seized power on April 6, 1919, and proclaimed a ‘Soviet Republic.’ Levine had agitated among his fellow soldiers for an Allied victory – using an argument identical to that of Hans Oster and future traitors. ‘It is necessary,’ Levine said, ‘that Germany is humiliated: that the colonial troops of France and England march through the Brandenburg Gate.’

Himmler’s diaries and letters still make no mention of Jews but the backdrop to later events was already forming. The German government in Berlin, under socialist chancellor Friedrich Ebert, ordered the truncated army to crush the ‘Soviet Republic’ of Bavaria. Aided by the Free Corps and a substantial Bavarian army contingent under Colonel Franz Ritter von Epp it was bloodily suppressed, but not before Levine’s men took scores of middle-class burghers hostage, along with members of the right-wing Thule Society, and locked them away in the Luitpold Gymnasium building. These hostages were taken out two at a time, and bludgeoned and shot to death on the last night of April 1919. Levine’s accomplices were shot out of hand (except for Tovia Axelrod, who claimed Russian diplomatic status). Levine was executed by firing squad at Munich’s Stadelheim prison on July 9, of which we shall occasionally hear more.

___________

Irving’s book can be purchased on his website.