‘There is no crime for those who have Christ.’

—St. Shenoute

The destroyers came from out of the desert. Palmyra must have been expecting them: for years, marauding bands of bearded, black-robed zealots, armed with little more than stones, iron bars and an iron sense of righteousness had been terrorizing the east of the Roman Empire.

Their attacks were primitive, thuggish, and very effective. These men moved in packs— later in swarms of as many as five hundred—and when they descended utter destruction followed. Their targets were the temples and the attacks could be astonishingly swift. Great stone columns that had stood for centuries collapsed in an afternoon; statues that had stood for half a millennium had their faces mutilated in a moment; temples that had seen the rise of the Roman Empire fell in a single day.

This was violent work, but it was by no means solemn. The zealots roared with laughter as they smashed the ‘evil’, ‘idolatrous’ statues; the faithful jeered as they tore down temples, stripped roofs and defaced tombs. Chants appeared, immortalizing these glorious moments. ‘Those shameful things,’ sang pilgrims, proudly; the ‘demons and idols… our good Saviour trampled down all together.’ Zealotry rarely makes for good poetry.

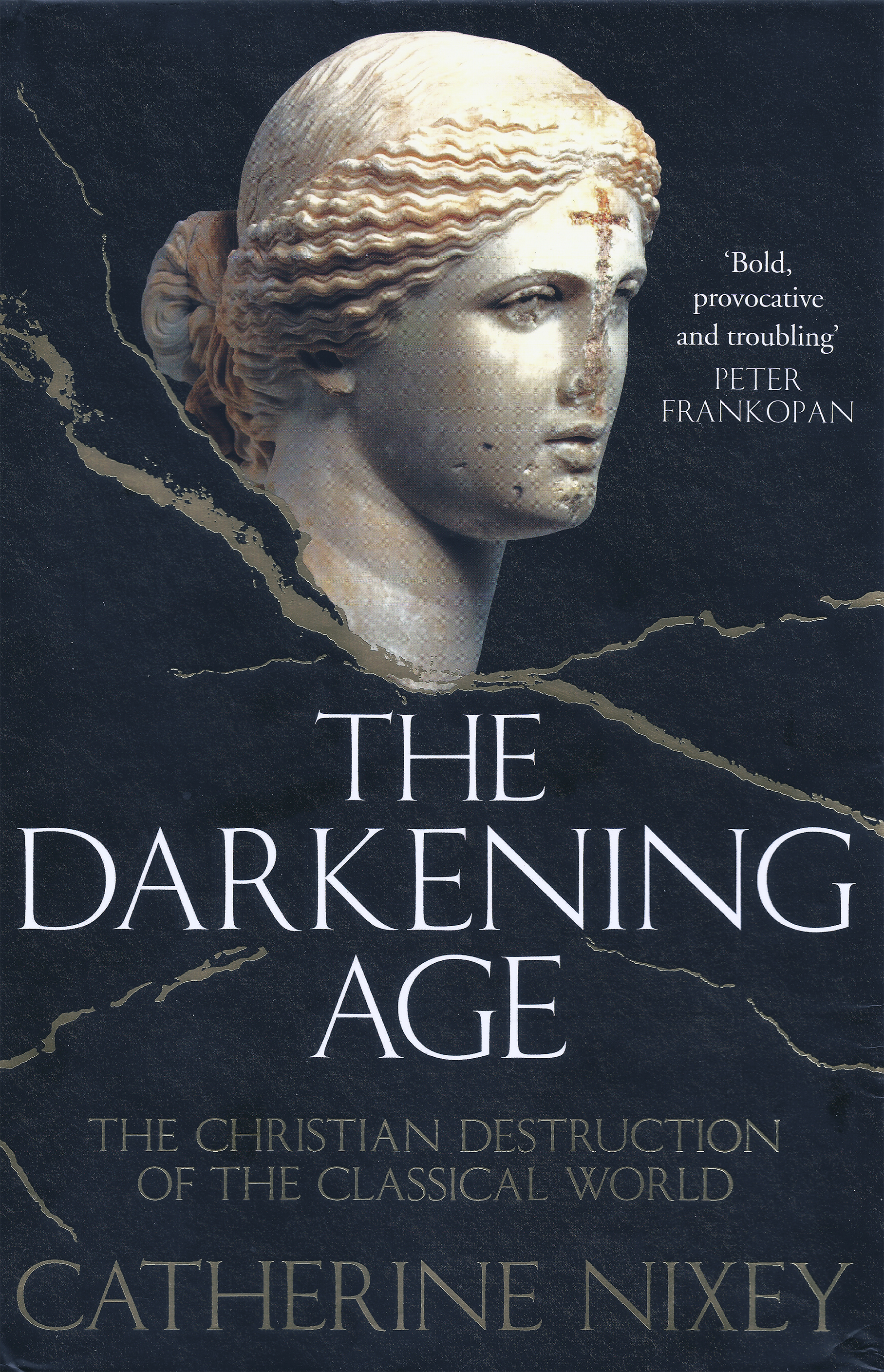

In this atmosphere, Palmyra’s temple of Athena was an obvious target. The handsome building was an unapologetic celebration of all the believers loathed: a monumental rebuke to monotheism. Go through its great doors and it would have taken your eyes a moment, after the brightness of a Syrian sun, to adjust to the cool gloom within. As they did, you might have noticed that the air was heavy with the smoky tang of incense, or perhaps that what little light there was came from a scatter of lamps left by the faithful. Look up and, in their flickering glow, you would have seen the great figure of Athena herself.

The handsome, haughty profile of this statue might be far from Athena’s native Athens, but it was instantly recognizable, with its straight Grecian nose, its translucent marble skin and the plump, slightly sulky mouth. The statue’s size—it was far taller than any man—might also have impressed. Though perhaps even more admirable than the physical scale was the scale of the imperial infrastructure and ambition that had brought this object here. The statue echoed others that stood on the Athenian Acropolis, well over a thousand miles away; this particular version had been made in a workshop hundreds of miles from Palmyra, then transported here at considerable difficulty and expense to create a little island of Greco-Roman culture by the sands of the Syrian desert.

Did they notice this, the destroyers, as they entered? Were they, even fleetingly, impressed by the sophistication of an empire that could quarry, sculpt then transport marble over such vast distances? Did they, even for a moment, admire the skill that could make a kissably soft-looking mouth out of hard marble? Did they, even for a second, wonder at its beauty?

It seems not. Because when the men entered the temple they took a weapon and smashed the back of Athena’s head with a single blow so hard that it decapitated the goddess. The head fell to the floor, slicing off that nose, crushing the once smooth cheeks. Athena’s eyes, untouched, looked out over a now-disfigured face.

Mere decapitation wasn’t enough. More blows fell, scalping Athena, striking the helmet from the goddess’s head, smashing it into pieces. Further blows followed. The statue fell from its pedestal, then the arms and shoulders were chopped off. The body was left on its front in the dirt; the nearby altar was sliced off just above its base.

Only then does it seem that these men—these Christians—felt satisfied that their work was done. They-melted out once again into the desert. Behind them the temple fell silent. The votive lamps, no longer tended, went out. On the floor, the head of Athena slowly started to be covered by the sands of the Syrian desert.

The ‘triumph’ of Christianity had begun.