Note of the Ed.: The main weakness that the Aryan faces before the Jew is the lack of solidarity to even recognise his martyrs. Contrast this attitude with how the Jew commemorates every single historical grievance; for example, when a Greek Seleucid king tried to destroy Judaism centuries before the Common Era.

The parabalani were Christian thugs that blindly obeyed the bishop of Alexandria. Since Aryans fail to honour their martyrs (Agora is a philo-Semitic film—not a good example of honouring an Aryan martyr of Semitic thugs), it would be helpful to imagine the parabalani as the Faith Militant in the TV series Game of Thrones. But this comparison, like the Spanish movie Agora starring non-Aryan Rachel Weisz as Hypatia, is deceiving. The historical parabalani were probably Christian Semites, as suggested in Evropa Soberana’s essay on Judea vs. Rome.

In chapter nine of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey wrote:

______ 卐 ______

Hypatia of Alexandria was born in the same city as the parabalani and yet a world away from them. While they spent their days toiling among the filthy and the dying, this aristocratic intellectual spent her days working with abstract mathematical theories and astrolabes. Hypatia was not only a philosopher; she was also a brilliant astronomer and the greatest mathematician of her generation. The Victorians, who became much taken with her, granted her other graces posthumously. One famous painting shows her draped naked against an altar, her nubile body shielded by little more than her tumbling tawny locks. A novel about her by the Reverend Charles Kingsley, author of the children’s novel The Water Babies, is rich in such breathless phrases as ‘the severest and grandest type of old Greek beauty’ and in musings on her ‘curved lips’ and the ‘glorious grace and beauty of every line’…

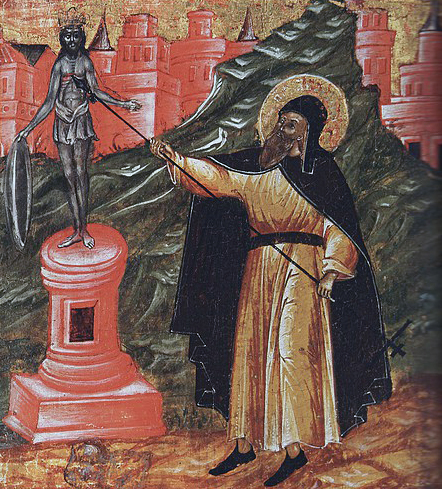

After razing Serapis the Christians had gone on vicious rampage through the city and its 2,500 shrines, temples and religious sites. Busts of Serapis previously stood in streets, wall niches and above doorways had been removed—’cleansed’. The Christians had ‘so cut and filed [them] away that not even a trace or mention of [Serapis] or any other demon remained anywhere. In their place everyone painted the sign of the Lord’s cross on door posts, entrances, walls and columns.’ Later, with bolder finality, crosses were carved in.

The city’s intellectual life had suffered. The final remnants of the Great Library had gone, vanishing along with the temple. Many of Alexandria’s intellectuals had gone too, fleeing to Rome, or elsewhere in Italy, or anywhere they could to get away from this frightening city’…

[For the Christian mind] Hypatia was not a philosopher: she was a creature of Hell. It was she who was turning the entire city against God with her trickery and her spells. She was ‘atheizing’ Alexandria. Naturally, she seemed appealing enough—but that was how the Evil One worked. Hypatia, they said, ‘had beguiled many people through satanic wiles’. Worst of all, she had even beguiled Orestes. Hadn’t he stopped going to church? It was clear: she had beguiled him through her magic’. This could not be allowed to continue.

One day in March AD 415, Hypatia set out from her home to go for her daily ride through the city. Suddenly; she found her way blocked by a ‘multitude of believers in God’. They ordered her to get down from her chariot. Knowing what had recently happened to her friend Orestes, she must have realized as she climbed down that her situation was a serious one. She cannot possibly have realized quite how serious.

As soon as she stood on the street, the parabalani, under the guidance of a Church magistrate called Peter—‘a perfect believer in all respects in Jesus Christ’—surged round and seized ‘the pagan woman’.

They then dragged Alexandria’s greatest living mathematician through the streets to a church. Once inside, they ripped the clothes from her body then, using broken pieces of pottery as blades, flayed her skin from her flesh. Some say that, while she still gasped for breath, they gouged out her eyes.

Once she was dead, they tore her body into pieces and threw what was left of the ‘luminous child of reason’ onto a pyre and burned her.