by Evropa Soberana

Consequences of the Great Jewish Revolt

In the year 73, after seven long years of an incredibly bloodthirsty war against the greatest military power on the planet, Judea as a whole was devastated; Jerusalem reduced to ashen ruins, and the Temple completely destroyed, except for a wall that remained standing, the Mur des Lamentations. Judea became a separate province, and the Legio X Fretensis permanently camped in the Jewish capital.

Once more: according to ancient sources, 1,100,000 Jews died during the siege and during the legions’ invasion, and another 97,000, including the leaders Simon Bar Giora and John of Giscala, were captured and sold as slaves throughout the Roman Empire. The vestiges of independence and political unity of the Jewish quarter were pulverized, and the Jews became again a people without a country.

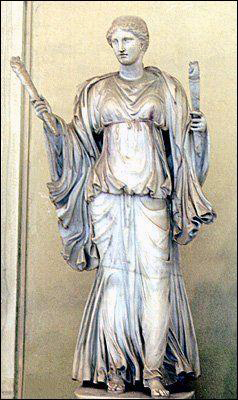

Once re-conquered the whole province of Judea, Rome coined commemorative coins on which appeared the profile of Emperor Vespasian and, on the other side, the inscription IVDEA CAPTA (conquered Judea), under which Judea was represented by a crying woman.

The Jewish rebellion was condemned as a kamikaze action from the beginning. Simply, the Roman Empire was a force too irresistible, and only the fundamentalist fanaticism, preached by minority social sectors, could drag Jewry to fight until the end in a way so tenacious with an enemy that was the bearer of an infinitely superior culture and, above all, of a better and more effective way of acting in the world. Will and faith may move mountains. In this case however the Jews did not achieve miracles but the destruction of their holy land and the hardening of the Roman occupation.

The date of the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 signals the beginning of the so-called Galut or Diaspora: the dispersion of the Jews throughout the world. In reality, the Jews were already more numerous outside Judea than in Judea—the largest Jewish population in the world was in Alexandria—, but the destruction of their capital decapitated the Judaic centralism and further fostered this diaspora process, favouring autonomous developments; the typical stateless feeling, and the rise of that characteristic cosmopolitanism.

Vespasian had the Jews of Judea scattered throughout Italy, Greece and, above all, North Africa and Asia Minor, believing that this was the end of the Jewish danger to the Empire.

Upon returning to Rome, the triumphant Titus solemnly rejected the crown of laurels of victory offered by the Roman people, claiming that he fulfilled the divine will and that ‘there is no merit in defeating a people that has been abandoned by their own god’. Shortly afterwards the Romans erected an arc of triumph, under which no Jew—at least no traditionalist Jew—still passes today. The arch of Titus, erected in Rome to commemorate the capture of Jerusalem, shows the Roman legionaries transporting the fruits of the looting of the temple, highlighting the giant menorah.

This is a key moment in Jewish history. The Jews saw how their achievements were crushed by a proud European empire, how their relics were trampled by Roman sandals and how their sacrosanct Temple was burned by flames. To see it destroyed was a huge shock in the collective psychology of Jewry, filling the Jews with resentment and desires for revenge against what they knew of Europe: the Greek and Roman communities.

Rome might have easily been able to exterminate all the Jews of Judea if she had wanted, but Rome did not, as it seemed that the Jewish power was finished. The Jews had been traumatized, and their tribal pride shattered. But, far from neutralising them, this psychological shock on their collective unconscious fed them cruel desires for revenge.