Note of the Editor: In this section Deschner says:

Therein lies the destructive tendency, of consequences that even reach us today, that instead of the ‘natural cosmos’ there is an ‘ecclesiastical cosmos’: a radical religious anthropocentrism, whose numerous repercussions and ‘progress’ endure beyond medieval theocracy [emphasis added].

Bingo! This is exactly what Savitri Devi tried to convey in Impeachment of Man, and also the Nazis right after they reached power.

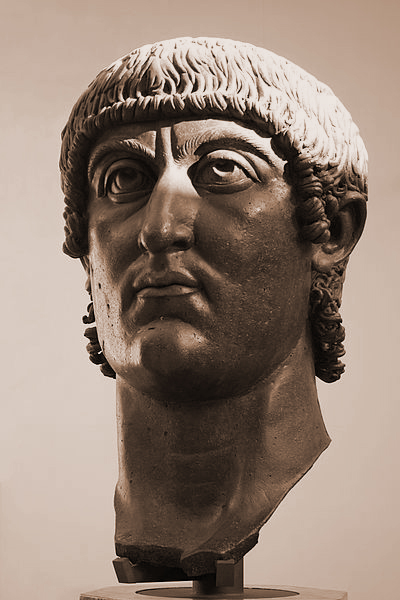

Pay due attention how these early Christian writers refer to the adepts of Greco-Roman culture as ‘gentiles’ (the painting in this post depicts Clement, author of Exhortations to Gentiles).

______ 卐 ______

Below, abridged translation from the first volume of Karlheinz

Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums

(Criminal History of Christianity)

The defamation of the cosmos and pagan religion and culture (Aristides, Athenagoras, Tatian, Tertullian, Clement and others)

Aristides

By the middle of the 2nd century, Aristides, one of the first apologists, whipped (in a text of apologetics that was not discovered until 1889 in the monastery of St Catherine of Sinai) the divinization of water, fire, winds, sun and, of course, the cult of the land; this being the place ‘where the filth of humans and animals, both wild and domestic… and the decomposition of the dead’, ‘recipient of corpses’.

Nothing, then, of the animal kingdom or the vegetable kingdom. Nothing of pleasure. And the polytheistic worlds are ‘madness’, ‘blasphemous, ridiculous and foolish talk’, which are the source of ‘all evil, hideous and repugnant’, ‘great vices’, of ‘endless wars, great famines, bitter captivity, and absolute misery’, all of which falls upon humanity ‘because of paganism’ and only for that.

Athenagoras

[On the other hand], at the end of the 2nd century the Athenian Athenagoras wants to see God, the father of reason, even in creatures devoid of it, and demands that the image of God be honoured not only in the human figure, but also in birds and terrestrial animals. Prudently, this Christian declares that ‘it is necessary that each one choose the gods of his preference’. Athenagoras does not harbour the intention to attack their images and does not even deny that they are capable of working miracles; Augustine takes a very similar stance.

How humble, or could almost say pious, Athenagoras seems in his A Plea for the Christians, when he asks for the ‘indulgence’ of the pagans Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, and praises their ‘prudent government’, their ‘kindness and clemency’, their ‘peace of mind and love of humans’, their ‘eagerness to know’, their ‘love of truth’ and their ‘beneficent actions’. He even assigns them honorary titles that did not correspond to them.

Tatian

However, at the same time, that is, towards 172, the Eastern Tatian writes a tremendous philippic against paganism. For this disciple (Christianized in Rome) of St Justin and future leader of the Encratites ‘heresy’, for the ‘barbarian philosopher Tatian’, as he called himself, the pagans are pretentious and ignorant, quarrelsome and flatterers.

They are full of ‘pride’ and ‘bell-like phrases’, but also of lust and lies. Their institutions, their customs, their religion and their sciences are nothing more than ‘follies’, ‘stupidity under multiple disguises’, ‘aberrations’. In his Oratio ad Graecos Tatian criticizes ‘the talk of the Romans’, ‘the frivolity of the Athenians’, ‘the innumerable mob of your useless poets, your concubines and other parasites’.

The ex-pupil of the sophists finds ‘lack of measure’ in Diogenes, ‘gluttony’ in Plato, ‘ignorance’ in Aristotle, ‘gossip of old women’ in Pherecydes and Pythagoras, ‘vanity’ in Empedocles. Sappho is no more than a ‘dishonest female, a prey to wrath of the uterus’, Aristippus a ‘lustful hypocrite’, Heraclitus a ‘vain self-taught’. In a word: ‘They are charlatans not doctors’, ironizes the Christian, ‘great in words but lacking in knowledge’, who ‘walk on hooves like wild animals’.

Tatian makes a tabula rasa of the classical rhetoric, of the schools, of the theatre, ‘those hemicycles where the public greets listening to filth’. Even the plastic arts (by theme and chosen models), and even what the whole world has admired and still admires, the poetry and philosophy of the Greeks, Tatian continually opposes the ‘frivolity’, ‘folly’, the ‘sickness’ of paganism to Christian ‘prudence’. Faced with ‘the rival and deceitful doctrines of those whom the devil makes blind’ he opposes the ‘teachings of our wisdom’.

With this discourse (‘unique and forceful requisition against all the achievements of the Hellenic spirit in all disciplines’ according to Krause) it begins the undermining of all pagan culture, followed by ostracism and almost total oblivion in the West for more than a millennium.

Tatian militated on the very front of the ancient Church—which stretched from St Ignatius (who rejected all contact with pagan literature and could almost be said that rejected instruction in general) and his co-religionist Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna, the polygraph Hermias and his Satire on pagan philosophers as crude as elemental, the father of the Church Irenaeus, the bishop Theophilus of Antioch and others who manifested their unrest against the old philosophy—, condemned as ‘false speculations’, ‘ravings, absurd, delusions of reason, or all these things at once’.

According to St Theophilus (a rather mediocre spirit, but the head of a prestigious site), what the representatives of Greek culture spread, without exception, is nothing more than ‘babble’, ‘useless talk’, since ‘they have not had the less hint of truth’, ‘have not found even the slightest bit of it’.

Tertullian

For Tertullian, the height of impiety and the culmination of the seven deadly sins, which are generally assumed in the Gentiles, is the worship of multiple gods, not taking into account that in the end these are but the forces of nature personified and deified, or those of sexual potency. Tertullian, perhaps more than any other Christian author before him, undertook a systematic struggle against this worship.

Tertullian notes with satisfaction that the pagans had little respect for their own idols and for the uses of their religion. He puts in sights the impassibility of the gods, the indignity of their myths; he mocks and gets scandalised that Christians cannot go anywhere without stumbling over gods. He prohibits them from any activity remotely related to ‘idolatry’, as well as the elaboration and sale of images and all professions useful to paganism, including military service.

Clement

Clement

Even a friend of Greek philosophy as Clement of Alexandria, in his Exhortations to Gentiles rebutted all those ‘sanctified myths’, ‘impious altars’, ‘diviners and insane and useless oracles’ and all their ‘schools of sophistry for unbelievers and gambling dens where madness abounds’.

As regards the ‘mysterious cults of the ungodly’ Clement intends to ‘reveal the delusions hidden in them’, their ‘holy frenzy’ since there is nothing more in them than ‘deceitful orgies’, ‘totally inhuman’, ‘seed of all evil and perdition’, ‘abominable cults’ that would no doubt only impress ‘the most uncultured barbarians among the Thracians, the most foolish among the Phrygians, and the most superstitious among the Greeks’.

Christians of antiquity did not understand the fascinating cycle of the life of plants, so celebrated by the pagans, or the interpretation of ancient myths in relation to fecundity, which implied the participation in tellurian and cosmic realities, as well as the experience, deeply religious, of the echo of the beautiful and the vital in every human being. Therein lies the destructive tendency, of consequences that even reach us today, that instead of the ‘natural cosmos’ there is an ‘ecclesiastical cosmos’: a radical religious anthropocentrism, whose numerous repercussions and ‘progress’ endure beyond medieval theocracy.

While condemning the divinization of the Cosmos, Clement launches in his Protrepticus a systematic anathema against sexuality, so linked with pagan cults, ‘with your demons and your gods and demigods, properly called as if we were talking about semi-donkeys [mules]’.

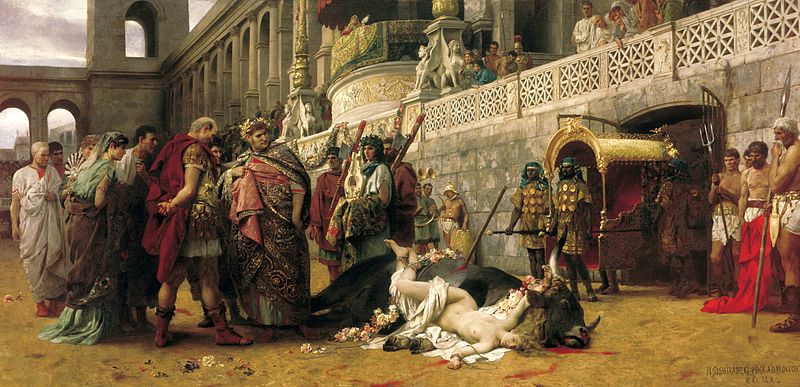

At the beginning of the 4th century, the Synod of Elvira promulgated a series of anti-pagan provisions: against ‘worship of idols’, against magic, against pagan customs, against marriage between Christians and pagans or idolatrous priests, all sanctioned with the highest ecclesiastical penalties. The pagan cult involved excommunication even in articulo mortis, as well as for murderers and fornicators. However, the council in question abstained from extremist positions. In Canon 60, for example, it denied the categorisation of martyrs to those who had perished during the tumults resulting from the destruction of ‘idolatrous images’. This was because Christianity was not yet an authorized religion.

The tone changed when it was elevated to the category of official religion. In the conflict with the old believers the great inflection occurs in 311, when emperor Galerius authorized Christianity, albeit grudgingly.