I wouldn’t like to start talking about Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra without saying something about my previous post, ‘Lebensborn’.

See my recent exchange with Greg Johnson (screenshot here). In his podcast with Joel Davis, Johnson mentioned the term ‘unnecessary suffering’ to substantiate why he rejects Nazism. Since my sacred words are Eliminate all unnecessary suffering, as can be seen in my latest books which I will translate, I feel compelled to clarify this point.

The sufferings that the Third Reich inflicted on many Caucasoids were necessary, not unnecessary. It is impossible to conquer an entire continent for the pure Aryan—think of Eduardo Velasco’s essay on the Heartland—without inflicting suffering on the ancient aborigines. If the normie Matt Walsh was recently able to glorify the Anglo-Saxon conquest of America to the detriment of the indigenous, why not also glorify the plans to conquer the Heartland for the pure Aryan? If the sufferings of the Amerindians were necessary for the creation of the US, why not see that the sufferings of the ‘half-gook’, as Maurice calls them, were also necessary? After all, the Anglo-Saxon’s intervention to abort Hitler’s Master Plan East has been so catastrophic that the white man is likely to become extinct!

As my books have yet to be translated, the distinction between necessary suffering and unnecessary suffering is unclear. But the axiological gulf that separates me from white nationalists might be better understood if I were to begin to offer my views on the protagonists of Christian civilisation. And since I have dedicated myself to writing in Spanish, what better than to begin with the author of Don Quixote?

Cervantes at the battle of Lepanto, by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau.

Unlike me—an obscure writer who except for the warm opinions of some visitors living in other countries lives in almost absolute isolation—, Cervantes was a man of his time; so much so that in the neighbourhood of Madrid where he lived other great writers of the time such as Lope de Vega and Quevedo resided. But to understand the writers of the so-called golden age of Spanish literature, it is necessary to contextualize them in their historical moment.

The maximum aspiration of Charles V was to create a Catholic empire: a dream that could never be fulfilled because in his dominions the germ of the Protestant rupture was born. And something similar could be said of Philip II, who tried to make England bend the knee before Rome.

Although of my middle and high school teachers, the only one I remember with respect is Soledad Anaya Solórzano, my literature teacher (who was also the teacher of Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize winner in literature), I confess that despite being high culture, I reject Spanish literature including its classics.

The reason is simple. No one in Spanish literature has challenged the dogma. Exceptions like Eduardo Velasco are exceptions that confirm the rule (and had it not been for me, his work in the blogosphere would have been lost after his death). Why should we admire a literature that, although magnificent in form, has been unable to escape the Christian / neochristian matrix? Let’s recall one of the essays on this site in which the German Albus said that the first great genius to compose degenerate music was Johann Sebastian Bach (see e.g., pages 149-155 of Daybreak). Of course, this criticism could be extended to many other protagonists of Christian civilisation: since it was written by ‘men of their time’, the most popular European and Western literature never question the paradigm in turn.

It is true that, like Shakespeare, Cervantes didn’t play into the hands of the Church and from that point of view their secularized literary output in an era of religious intolerance had its value. But in this age, which requires fanatic priests to unplug whites from the matrix that destroys them, it is literature that already tastes rancid to us. Moreover, there were contemporaries of Cervantes who did play into the hands of the Church. The moralizing content of Mateo Alemán’s work, for example, was ideologically in line with the spirit of the Counter-Reformation; and let’s not even talk about the mystical painting of El Greco.

To give a very obvious example. Neither Cervantes nor other so-called giants of the Spanish Golden Age could have criticised the Church in times when it was celebrating autos de Fe. Throughout the 16th century the Inquisition acted with increasing harshness to repress any outbreak of the so-called Protestant heresy. Those condemned to death were publicly burned alive in an auto de Fe, and there was clemency only in case of recantation, when they were executed by garrote before being burned.

From the POV of the sacred words, which includes not only the 4 words but the 14 words, what real value can literature from ‘men of their time’ have, to use Savitri Devi’s expression?

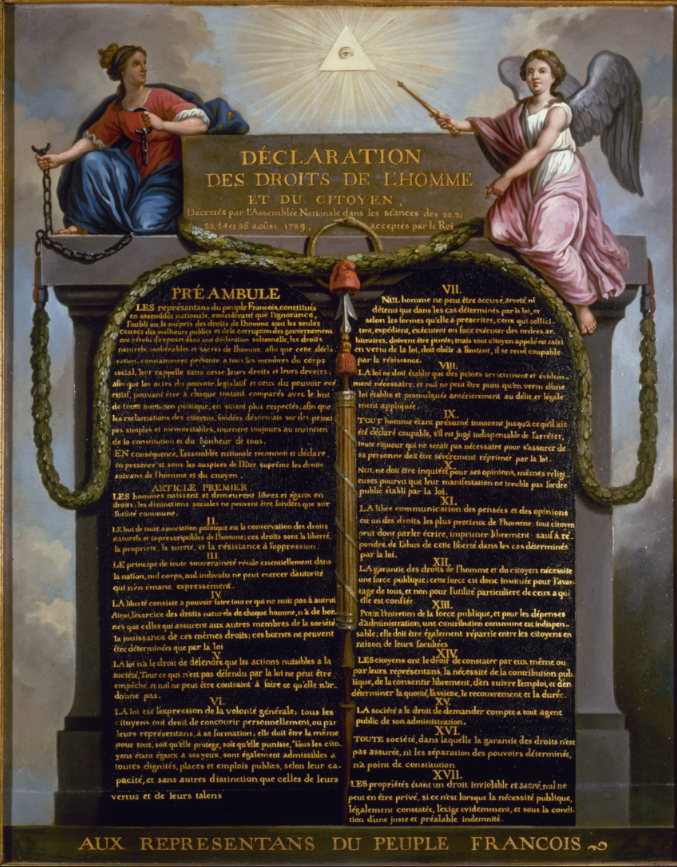

Philip II, King of Spain when Cervantes was alive, with his son contemplating an auto de Fe in Valladolid in which members of the newly discovered Protestant communities of Seville and Valladolid were burned.

What do I gain by reading Lope de Vega, the ‘monster of nature’ as Cervantes called him due to his abundant literary production, if due to circumstances he was unable to criticise the burning of Protestants in Valladolid? In other words: if someone fights the current paradigm, he also fights his art, be it Lope’s or Bach’s. Although we cannot blame the artist for his circumstances—in the 1590 edition of Cervantes’ first novel we can read on the title page Impresa con licencia de la Santa Inquisición (Printed with license from the Holy Inquisition)—the priest of the sacred words sees little, if any, value coming from the pens of artists whose minds were chained to the worldview of the time.

The Spanish Visigoths had begun to interbreed since the 7th century (see William Pierce’s Who We Are). Compared to the already mixed ethnicity of the Spanish a thousand years later, only the defeat of the Invincible Armada by Elizabeth’s England tipped the balance to a more Aryan side of Europe. Although the English were also infected with Christian ethics and capable of bringing mixed couples to the marriage altar, by the time of Cervantes and Shakespeare their ‘ethics’ hadn’t metastasized to the incredible anti-white levels we see in today’s UK.

In this new series I will be talking about other protagonists of the Christian civilisation from the point of view of the contemporary priest of the sacred words (in plain English, National Socialism after 1945).