The History of the Decline and Fall

of the Roman Empire

Chapter XXIII

Reign of Julian

Part V

The zeal of the ministers of Julian was instantly checked by the frown of their sovereign; but when the father of his country declares himself the leader of a faction, the license of popular fury cannot easily be restrained, nor consistently punished. Julian, in a public composition, applauds the devotion and loyalty of the holy cities of Syria, whose pious inhabitants had destroyed, at the first signal, the sepulchers of the Galilæans; and faintly complains, that they had revenged the injuries of the gods with less moderation than he should have recommended.

This imperfect and reluctant confession may appear to confirm the ecclesiastical narratives; that in the cities of Gaza, Ascalon, Cæsarea, Heliopolis, &c., the Pagans abused, without prudenceor remorse, the moment of their prosperity. That the unhappy objects of their cruelty were released from torture only by death; and as their mangled bodies were dragged through the streets, they were pierced (such was the universal rage) by the spits of cooks, and the distaffs of enraged women; and that the entrails of Christian priests and virgins, after they had been tasted by those bloody fanatics, were mixed with barley, and contemptuously thrown to the unclean animals of the city.

Such scenes of religious madness exhibit the most contemptible and odious picture of human nature; but the massacre of Alexandria attracts still more attention, from the certainty of the fact, the rank of the victims, and the splendor of the capital of Egypt. George, from his parents or his education, surnamed the Cappadocian, was born at Epiphania in Cilicia, in a fuller’s shop. From this obscure and servile origin he raised himself by the talents of a parasite; and the patrons, whom he assiduously flattered, procured for their worthless dependent a lucrative commission, or contract, to supply the army with bacon. His employment was mean; he rendered it infamous.

He accumulated wealth by the basest arts of fraud and corruption; but his malversations were so notorious, that George was compelled to escape from the pursuits of justice. After this disgrace, in which he appears to have saved his fortune at the expense of his honor, he embraced, with real or affected zeal, the profession of Arianism. From the love, or the ostentation, of learning, he collected a valuable library of history rhetoric, philosophy, and theology, and the choice of the prevailing faction promoted George of Cappadocia to the throne of Athanasius.

The entrance of the new archbishop was that of a Barbarian conqueror; and each moment of his reign was polluted by cruelty and avarice. The Catholics of Alexandria and Egypt were abandoned to a tyrant, qualified, by nature and education, to exercise the office of persecution; but he oppressed with an impartial hand the various inhabitants of his extensive diocese.

The primate of Egypt assumed the pomp and insolence of his lofty station; but he still betrayed the vices of his base and servile extraction. The merchants of Alexandria were impoverished by the unjust, and almost universal, monopoly, which he acquired, of nitre, salt, paper, funerals, &c.: and the spiritual father of a great people condescended to practise the vile and pernicious arts of an informer.

The Alexandrians could never forget, nor forgive, the tax, which he suggested, on all the houses of the city; under an obsolete claim, that the royal founder had conveyed to his successors, the Ptolemies and the Cæsars, the perpetual property of the soil. The Pagans, who had been flattered with the hopes of freedom and toleration, excited his devout avarice; and the rich temples of Alexandria were either pillaged or insulted by the haughty prince, who exclaimed, in a loud and threatening tone, “How long will these sepulchres be permitted to stand?”

Under the reign of Constantius, he was expelled by the fury, or rather by the justice, of the people; and it was not without a violent struggle, that the civil and military powers of the state could restore his authority, and gratify his revenge. The messenger who proclaimed at Alexandria the accession of Julian, announced the downfall of the archbishop. George, with two of his obsequious ministers, Count Diodorus, and Dracontius, master of the mint were ignominiously dragged in chains to the public prison. At the end of twenty-four days, the prison was forced open by the rage of a superstitious multitude, impatient of the tedious forms of judicial proceedings.

The enemies of gods and men expired under their cruel insults; the lifeless bodies of the archbishop and his associates were carried in triumph through the streets on the back of a camel; and the inactivity of the Athanasian party was esteemed a shining example of evangelical patience. The remains of these guilty wretches were thrown into the sea; and the popular leaders of the tumult declared their resolution to disappoint the devotion of the Christians, and to intercept the future honors of these martyrs, who had been punished, like their predecessors, by the enemies of their religion.

The fears of the Pagans were just, and their precautions ineffectual. The meritorious death of the archbishop obliterated the memory of his life. The rival of Athanasius was dear and sacred to the Arians, and the seeming conversion of those sectaries introduced his worship into the bosom of the Catholic church.

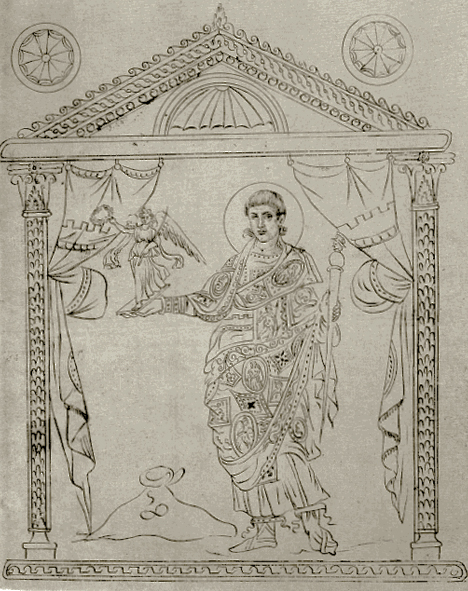

The odious stranger, disguising every circumstance of time and place, assumed the mask of a martyr, a saint, and a Christian hero; and the infamous George of Cappadocia has been transformed into the renowned St. George of England, the patron of arms, of chivalry, and of the garter. About the same time that Julian was informed of the tumult of Alexandria, he received intelligence from Edessa, that the proud and wealthy faction of the Arians had insulted the weakness of the Valentinians, and committed such disorders as ought not to be suffered with impunity in a well-regulated state.

Without expecting the slow forms of justice, the exasperated prince directed his mandate to the magistrates of Edessa, by which he confiscated the whole property of the church: the money was distributed among the soldiers; the lands were added to the domain; and this act of oppression was aggravated by the most ungenerous irony. “I show myself,” says Julian, “the true friend of the Galilæans. Their admirable law has promised the kingdom of heaven to the poor; and they will advance with more diligence in the paths of virtue and salvation, when they are relieved by my assistance from the load of temporal possessions. Take care,” pursued the monarch, in a more serious tone, “take care how you provoke my patience and humanity. If these disorders continue, I will revenge on the magistrates the crimes of the people; and you will have reason to dread, not only confiscation and exile, but fire and the sword.”

The tumults of Alexandria were doubtless of a more bloody and dangerous nature: but a Christian bishop had fallen by the hands of the Pagans; and the public epistle of Julian affords a very lively proof of the partial spirit of his administration. His reproaches to the citizens of Alexandria are mingled with expressions of esteem and tenderness; and he laments, that, on this occasion, they should have departed from the gentle and generous manners which attested their Grecian extraction.

He gravely censures the offence which they had committed against the laws of justice and humanity; but he recapitulates, with visible complacency, the intolerable provocations which they had so long endured from the impious tyranny of George of Cappadocia. Julian admits the principle, that a wise and vigorous government should chastise the insolence of the people; yet, inconsideration of their founder Alexander, and of Serapis their tutelar deity, he grants a free and gracious pardon to the guilty city, for which he again feels the affection of a brother.

After the tumult of Alexandria had subsided, Athanasius, amidst the public acclamations, seated himself on the throne from whence his unworthy competitor had been precipitated: and as the zeal of the archbishop was tempered with discretion, the exercise of his authority tended not to inflame, but to reconcile, the minds of the people. His pastoral labors were not confined to the narrow limits of Egypt. The state of the Christian world was present to his active and capacious mind; and the age, the merit, the reputation of Athanasius, enabled him to assume, in a moment of danger, the office of Ecclesiastical Dictator.

Three years were not yet elapsed since the majority of the bishops of the West had ignorantly, or reluctantly, subscribed the Confession of Rimini. They repented, they believed, but they dreaded the unseasonable rigor of their orthodox brethren; and if their pride was stronger than their faith, they might throw themselves into the arms of the Arians, to escape the indignity of a public penance, which must degrade them to the condition of obscure laymen.

At the same time the domestic differences concerning the union and distinction of the divine persons, were agitated with some heat among the Catholic doctors; and the progress of this metaphysical controversy seemed to threaten a public and lasting division of the Greek and Latin churches. By the wisdom of a select synod, to which the name and presence of Athanasius gave the authority of a general council, the bishops, who had unwarily deviated into error, were admitted to the communion of the church, on the easy condition of subscribing the Nicene Creed; without any formal acknowledgment of their past fault, or any minute definition of their scholastic opinions.

The advice of the primate of Egypt had already prepared the clergy of Gauland Spain, of Italy and Greece, for the reception of this salutary measure; and, notwithstanding the opposition of some ardent spirits, the fear of the common enemy promoted the peace and harmony of the Christians. The skill and diligence of the primate of Egypt had improved the season of tranquillity, before it was interrupted by the hostile edicts of the emperor. Julian, who despised the Christians, honored Athanasius with his sincere and peculiar hatred. For his sake alone, he introduced an arbitrary distinction, repugnant at least to the spirit of his former declarations.

He maintained, that the Galilæans, whom he had recalled from exile, were not restored, by that general indulgence, to the possession of their respective churches; and he expressed his astonishment, that a criminal, who had been repeatedly condemned by the judgment of the emperors, should dare to insult the majesty of the laws, and insolently usurp the archiepiscopal throne of Alexandria, without expecting the orders of his sovereign. As a punishment for the imaginary offence, he again banished Athanasius from the city; and he was pleased to suppose, that this act of justice would be highly agreeable to his pious subjects.

The pressing solicitations of the people soon convinced him, that the majority of the Alexandrians were Christians; and that the greatest part of the Christians were firmly attached to the cause of their oppressed primate. But the knowledge of their sentiments, instead of persuading him to recall his decree, provoked him to extend to all Egypt the term of the exile of Athanasius. The zeal of the multitude rendered Julian still more inexorable: he was alarmed by the danger of leaving at the head of a tumultuous city, a daring and popular leader; and the language of his resentment discovers the opinion which he entertained of the courage and abilities of Athanasius.

The execution of the sentence was still delayed, by the caution or negligence of Ecdicius, præfect of Egypt, who was at length awakened from his lethargy by a severe reprimand. “Though you neglect,” says Julian, “to write tome on any other subject, at least it is your duty to inform me of your conduct towards Athanasius, the enemy of the gods. My intentions have been long since communicated to you. I swear by the great Serapis, that unless, on the calends of December, Athanasius has departed from Alexandria, nay, from Egypt, the officers of your government shall pay a fine of one hundred pounds of gold. You know my temper: I am slow to condemn, but I am still slower to forgive.”

This epistle was enforced by a short postscript, written with the emperor’s own hand. “The contempt that is shown for all the gods fills me with grief and indignation. There is nothing that I should see, nothing that I should hear, with more pleasure, than the expulsion of Athanasius from all Egypt. The abominable wretch! Under my reign, the baptism of several Grecian ladies of the highest rank has been the effect of his persecutions.”

The death of Athanasius was not expressly commanded; but the præfect of Egypt understood that it was safer for him to exceed, than to neglect, the orders of an irritated master. The archbishop prudently retired to the monasteries of the Desert; eluded, with his usual dexterity, the snares of the enemy; and lived to triumph over the ashes of a prince, who, in words of formidable import, had declared his wish that the whole venom of the Galilæan school were contained in the single person of Athanasius. I have endeavored faithfully to represent the artful system by which Julian proposed to obtain the effects, without incurring the guilt, or reproach, of persecution.

But if the deadly spirit of fanaticism perverted the heart and understanding of a virtuous prince, it must, at the same time, be confessed that the real sufferings of the Christians were inflamed and magnified by human passions and religious enthusiasm. The meekness and resignation which had distinguished the primitive disciples of the gospel, was the object of the applause, rather than of the imitation of their successors.

The Christians, who had now possessed above forty years the civil and ecclesiastical government of the empire, had contracted the insolent vices of prosperity, and the habit of believing that the saints alone were entitled to reign over the earth. As soon as the enmity of Julian deprived the clergy of the privileges which had been conferred by the favor of Constantine, they complained of the most cruel oppression; and the free toleration of idolaters and heretics was a subject of grief and scandal to the orthodox party. The acts of violence, which were no longer countenanced by the magistrates, were still committed by the zeal of the people.

At Pessinus, the altar of Cybele was overturned almost in the presence of the emperor; and in the city of Cæsarea in Cappadocia, the temple of Fortune, the sole place of worship which had been left to the Pagans, was destroyed by the rage of a popular tumult. On these occasions, a prince, who felt for the honor of the gods, was not disposed to interrupt the course of justice; and his mind was still more deeply exasperated, when he found that the fanatics, who had deserved and suffered the punishment of incendiaries, were rewarded with the honors of martyrdom.

The Christian subjects of Julian were assured of the hostile designs of their sovereign; and, to their jealous apprehension, every circumstance of his government might afford some grounds of discontent and suspicion. In the ordinary administration of the laws, the Christians, who formed so large apart of the people, must frequently be condemned: but their indulgent brethren, without examining the merits of the cause, presumed their innocence, allowed their claims, and imputed the severity of their judge to the partial malice of religious persecution. These present hardships, intolerable as they might appear, were represented as a slight prelude of the impending calamities.

The Christians considered Julian as a cruel and crafty tyrant; who suspended the execution of his revenge till he should return victorious from the Persian war. They expected, that as soon as he had triumphed over the foreign enemies of Rome, he would lay aside the irksome mask of dissimulation; that the amphitheatre would stream with the blood of hermits and bishops; and that the Christians who still persevered in the profession of the faith, would be deprived of the common benefits of nature and society.

Every calumny that could wound the reputation of the Apostate, was credulously embraced by the fears and hatred of his adversaries; and their indiscreet clamors provoked the temper of a sovereign, whom it was their duty to respect, and their interest to flatter. They still protested, that prayers and tears were their only weapons against the impious tyrant, whose head they devoted to the justice of offended Heaven. But they insinuated, with sullen resolution, that their submission was no longer the effect of weakness; and that, in the imperfect state of human virtue, the patience, which is founded on principle, may be exhausted by persecution.

It is impossible to determine how far the zeal of Julian would have prevailed over his good sense and humanity; but if we seriously reflect on the strength and spirit of the church, we shall be convinced, that before the emperor could have extinguished the religion of Christ, he must have involved his country in the horrors of a civil war.