This topic is related to my work in Spanish, which deals precisely with parents who devour the souls of their children.

Author: C .T.

Good news!

The English translation of some pages from my book Hojas Susurrantes, very critical of an influential Jew, Sigmund Freud, has just been published in The Occidental Observer (here).

The English translation of some pages from my book Hojas Susurrantes, very critical of an influential Jew, Sigmund Freud, has just been published in The Occidental Observer (here).

A little black lady

who serves our cause!

In sharp contrast to the first ten minutes, the end of the video shows some awful anti-music played by niggers. This said, I love that the ZOG concept is becoming mainstream! Without realising it, this black lady is helping our cause. As I said in previous days regarding edgy podcasters, what we need now is for at least one Groyper to read a Hellstorm review as a prelude to drinking from this site’s wellspring.

In the video above, it’s clear how even Gentiles in the US Congress are guilty of the excessive empowerment of Jews. Sooner or later, racialists will have to confront the CQ. Sooner or later, the ideas of The West’s Darkest Hour (21st Century NS) will have to sink into the collective unconscious of the Aryan.

Snow White

The true story

Wow. What a find. I’ve always thought that fairy tales reflect realities that illustrate what I want to say in my trilogy of books I’m translating into English—and look what I found today!

In the real Middle Ages, not in fairy tales, some mothers—who we would now say suffered from malignant narcissism—killed their most beautiful daughters for reasons of power, if we understand the dynamics of the noble classes. (I couldn’t help but think of the infanticide campaign that my mother subtly unleashed during my puberty and that virulently culminated in my adolescence. But that’s another story.)

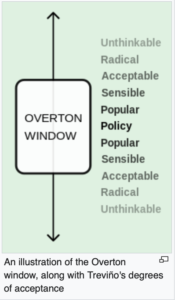

Overton

window

See YouTube

See YouTube

clip here.

Thanks, Bibi!

Regarding what’s been happening these past few days following Tucker’s interview with Nick, I’m astonished. Of course, the primary cause of this uproar isn’t due to this pair, but to Bibi Netanyahu’s blunder and his genocidal campaign in Gaza. In the days following October 7, 2023, almost all of American public opinion was in favour of Israel. As a result of Bibi’s blunder, for the first time in US history, the majority of Americans are on the side of Palestine!

Think about that.

What’s happening in the American collective unconscious is similar to a tectonic plate readjustment, with natural earthquakes and potential tsunamis producing geological changes: a huge opportunity that Tucker, Nick and many other podcasters have been able to seize.

Although this is a step in our direction, and although R.G. and Jamie are right that Americans aren’t ready for National Socialism, we must always keep in mind that Christianity is connected to the power of Jews in the West. I invite visitors to watch just ten seconds of this clip of Charlie Kirk from March 14, 2025 (“But I think you can acknowledge that we as Christians have to honor the Jews. You believe that?”). Ted Cruz, senator from Texas said similar things in his heated argument with Tucker earlier this year, and millions of evangelical Christians in North America think, or used to think, the same.

Jamie is right. Taking Christianity away from Americans is going to be a hard sell! That’s why I love the economists who predict the collapse of the dollar (a few months ago the ounce of gold was below $3,000 and now it has surpassed $4,000—it has to reach $27,000 or more for us to be talking about hyperinflation). But that won’t be enough, not barely enough to kill Christianity. What will really be apocalyptic is energy devolution thanks to peak oil (alas, unlike the collapse of the dollar, this process could take a century to unfold…).

Jamie is right. Taking Christianity away from Americans is going to be a hard sell! That’s why I love the economists who predict the collapse of the dollar (a few months ago the ounce of gold was below $3,000 and now it has surpassed $4,000—it has to reach $27,000 or more for us to be talking about hyperinflation). But that won’t be enough, not barely enough to kill Christianity. What will really be apocalyptic is energy devolution thanks to peak oil (alas, unlike the collapse of the dollar, this process could take a century to unfold…).

Anyway, and reiterating what I told the Groypers in my previous post: if we are to save the Aryan from extinction we must reject Christian ethics.

James Watson

See Devlin’s obituary

here, published today.

Groypers

This Monday I continue writing about what I said yesterday.

I have been watching my autobiographical videos that I recorded in Spain sixteen years ago about the devastating abuse I suffered at the hands of my parents as a teenager, and I realise that I don’t look so bad on camera. True, I am not white in the American sense of the word, which refers to Anglo-Germans north of the Rio Grande, but by Mediterranean standards I couldn’t say I looked too bad at fifty, when those videos were recorded. However, since I don’t know anything about software that can translate me into English, I will continue using text today.

The idea behind creating a channel is simply so that the Groypers can see me on Rumble, because I very much doubt they visit The West’s Darkest Hour. The urgent message I would like to convey to these young people so that they finish crossing the Rubicon towards NS is not hard to understand. But first of all, I would like to reiterate why I think it is a good idea to try to communicate with them.

If visitors remember what I said about my trip to Europe this year, which I recently linked to with a picture of me in Dachau, they will see that if Europeans are emasculated, it is simply because they aren’t allowed to speak. Giving my friends Chris and Joseph eight and seven years in prison for Thought Crime in the UK for what they said on Black Wolf Radio seems excessive even by the standards of Europe’s so-called soft totalitarianism! (and Canada and Australia are no much better when it comes to freedom of speech). Americans have a huge advantage: they are allowed to speak. That is why racialist webzine forums have flourished although, as Hitler well knew, that intellectual phase only fertilises the soil for the seed to germinate, whereas only the power of oratory can catapult a racialist to power.

From this angle, only Nick Fuentes is using oratory for this purpose, as seen in this YouTube video uploaded yesterday.

The reason I would like the message of this site to reach the ears of at least some Groypers is that, although I admire young Nick as the only orator at the moment, his message is contradictory due to his Catholicism.

Please understand me correctly. An American politician cannot be openly anti-Christian, as he would lose the votes of Christians if he wanted to come to power as Hitler did (and upon reaching it, eliminate superstitions such as parliamentarianism, etc., as Savitri Devi rightly said).

However, the new Führer must be aware of the Christian Question. And this, even though Hitler only spoke out about the CQ to his inner circle.

In Tucker’s interview with Fuentes, he asked him if he would ever run for president. Fuentes said maybe. But it is not the same for a Catholic like Fuentes to become president as it would be for a Groyper who thinks like Hitler: show yourself to the masses as a devout Christian, but reveal to your friends your true colours as a pantheist. And from this angle, it is necessary to criticise Fuentes.

Yesterday I saw a video uploaded a couple of days ago to YouTube. It shows part of Candace Owens’ interview with Fuentes, and I was struck by the fact that from the outset Fuentes admitted that, as a Catholic, he couldn’t oppose interracial marriage. Fuentes then spoke about Jared Taylor-like race realism, a point on which Owens is as ignorant as most Westerners. But even in that cordial segment of the interview—as cordial as the interview with Tucker—the contradiction between Fuentes’ Christian ethics and his racial realism is more than evident.

Considering what I recently said to my interlocutor Benjamin in the comments section, that crossing the psychological Rubicon is done step by step (even I took time to cross it since I recorded those videos about child abuse in Spain), the ideal situation would be for someone like Fuentes to become president. We can already imagine the difference between a Fuentes presidency and Trump’s abject international politics!

But what would happen to the country’s laws? Fuentes has said that power should not be relinquished (just what Hitler did when he became chancellor). Is it possible that in the future Fuentes, or someone like him, could become the first dictator of the US? Even in this fantastical scenario I see serious problems due to Fuentes’ Catholicism, and that is what I want to communicate to the Groypers.

But what would happen to the country’s laws? Fuentes has said that power should not be relinquished (just what Hitler did when he became chancellor). Is it possible that in the future Fuentes, or someone like him, could become the first dictator of the US? Even in this fantastical scenario I see serious problems due to Fuentes’ Catholicism, and that is what I want to communicate to the Groypers.

Let’s suppose that Fuentes is the dictator of the US. If we take into account what he said to the negress Owens, will there be Nuremberg Laws in his dictatorship? And the thorniest question: what about the 100 million non-Aryans living in the US? A true Christian cannot expel them, right?

If I, a true Hitlerist, were in power, it is clear what I would do—as any reader of William Pierce’s first novel can imagine. But the dictator Fuentes, because he constantly says that in the US he imagines the first thing is “Christ King,” would never dare to take that step… and over the centuries, with other Christian dictators, white Americans would become extinct. The dictator Fuentes and his successors would only have delayed the process that the Jewish zeitgeist is now accelerating: a boiling frog that doesn’t know it’s being slowly killed because of Xtian ethics.

This is what the Groypers who continue to take baby steps towards our side should know.

Rumble channel?

A few blocks from the studio where I now live, on the 20th of last month, a shocking revelation from someone about what I love most in the world (only my correspondent Benjamin knows the details) affected me so profoundly that I’ve been searching for defence mechanisms to free myself from intense anxiety and anguish!

Today, while walking down a quiet street in Coyoacán, it occurred to me that to combat this state of mind brought on by the unexpected revelation, I’ll have to do extraordinary things.

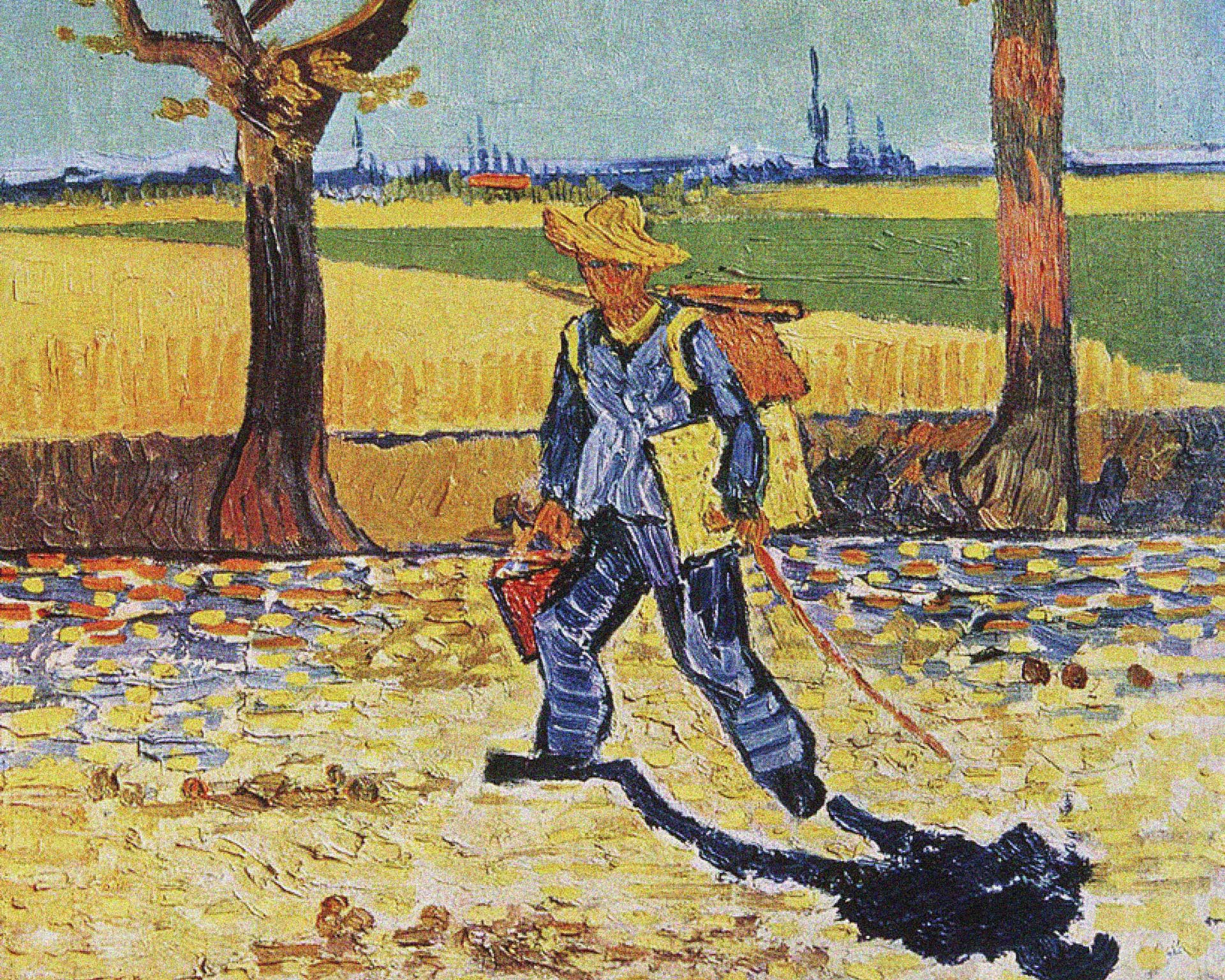

After returning to this continent from a Spanish island in 2009, I spent several months thinking about the life of Vincent van Gogh. The best of the several books I read then was a huge one my friend Paulina gave me, which contains all his paintings (it was one of the ones that got wet in this year’s flood, and it took me a long time to dry it in the sun).

Van Gogh’s Painter on his way to work.

Vincent had a phrase that I’ve liked ever since: “active melancholy.” He was an absolute workaholic who painted from sunrise to sunset, sometimes even at night (one of the reasons the stupid villagers of Arles in France were scandalised and hurt him horribly by calling him crazy).

Now that the revelation, the details of which only Ben knows, is eating away at my soul, and it seems it will continue for months, if not years, I thought I’d emulate Brother Vincent.

In my case, of course, that doesn’t just mean continuing to translate my books (I think the second one will be ready soon for visitors to obtain via Lulu Press). Since I now have to work day and night to try to exorcise what’s corroding my soul, why not finally start on an idea I’ve had for a while?

I’m referring to creating a channel on Rumble—only there would they not cancel me—with a catchy title like “Nick Fuentes Critic.”

Among white nationalists, Fuentes is the only online streamer who speaks like a real man, so I respect him immensely, truly. Since Tucker Carlson interviewed him, Fuentes has been widely mentioned both on MSM and on social media. (By the way, aside from The Occidental Observer, it’s a shame that the rest of the racialist forums seem to envy him.)

So, if I “go for it” by recording myself in my native language (Spanish) and learning to use AI programs to translate the videos into English (the most sophisticated programs even modify lip movements to reflect the English words), I’ll be working just as obsessively as Brother Vincent.

It’s a very artificial way of trying to reduce the pangs of the inner demon that presently gnaws at my soul (ideally, I’d solve the problem in the real world, but to do so legally I’d need 15 million Mexican pesos, no less). But that’s how all the creators who have become geniuses operated. Although this doesn’t mean I consider myself a genius, I know it’s the only way to distract myself from the existential crisis that has befallen me since last month.

So, let’s get to work!

Since I’m 67 years old and quite clumsy with computers, it will take me much longer to learn how to use AI translation programs. But as I said, I have no other option given the circumstances.

The idea is to present the things Fuentes says in his podcasts, but criticise them from a National Socialist perspective. I repeat: I have immense respect for this young man. Compared to him, the vast majority of white nationalists seem like eunuchs to me. But I believe that his Catholicism, and in particular his Christian ethics, is detrimental to his very purposes (see my recent posts about Fuentes, especially what I say about the need to create Dachau concentration camps in the US).

It will be quite amusing, given that both Fuentes and I have Mexican blood. But it’s not our Indigenous heritage that makes us speak with such brutal frankness. It’s Spanish blood. Did any of you live in Franco’s Spain, when men still spoke in the way men used to speak? That is the way Fuentes and I speak!

And if learning the ropes of using AI translators takes longer than expected, I could start commenting on Fuentes’s programs in text form, like this very post.

It’s an indirect way of introducing the white nationalist I admire most: by criticising him. Fuentes has just extended the Overton Window (the JQ) in the marketplace of ideas among conservative Republicans. What I want now is to extend it further among the Groypers themselves.

Of course, if someone wants to help me translate my videos into English, it would save me a ton of work, and I could focus exclusively on the content of the “Nick Fuentes Critic” channel.

Nick’s latest

video

Could a German who likes this video translate it with AI to see if it makes his compatriots grow some balls? (unlike Nick, all the white men I know behave like eunuchs!).

Greg Johnson says Nick doesn’t read. I am poor but could someone send Nick a copy of Hellstorm, and once he has assimilated it, a copy of Who We Are by Pierce?

The moment he incorporates this knowledge, with his balls he will take our message to another level…