Introduction

‘To historians is granted a talent that even the gods are denied—to alter what has already happened!’

I bore this scornful saying in mind when I embarked on this study of Adolf Hitler’s twelve years of absolute power. I saw myself as a stone cleaner—less concerned with architectural appraisal than with scrubbing years of grime and discoloration from the facade of a silent and forbidding monument. I set out to describe events from behind the Führer’s desk, seeing each episode through his eyes.

The technique necessarily narrows the field of view, but it does help to explain decisions that are otherwise inexplicable. Nobody that I knew of had attempted this before, but it seemed worth the effort: after all, Hitler’s war left forty million dead and caused all of Europe and half of Asia to be wasted by fire and explosives; it destroyed Hitler’s ‘Third Reich,’ bankrupted Britain and lost her the Empire, and it brought lasting disorder to the world’s affairs; it saw the entrenchment of communism in one continent, and its emergence in another.

In earlier books I had relied on the primary records of the period rather than published literature, which contained too many pitfalls for the historian. I naïvely supposed that the same primary sources technique could within five years be applied to a study of Hitler.

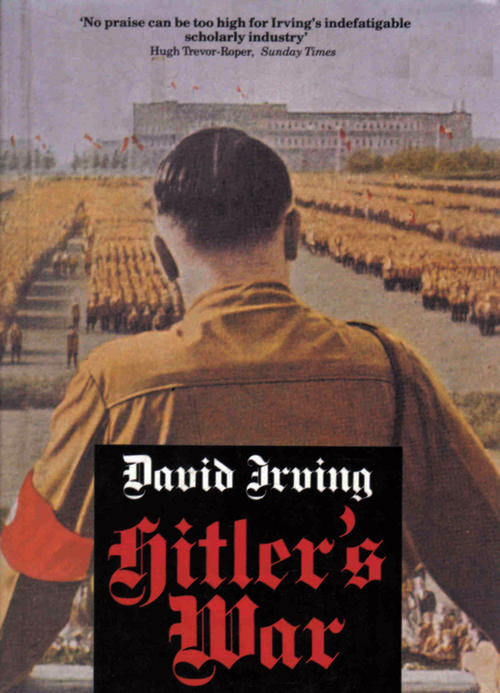

In fact it would be thirteen years before the first volume, Hitler’s War, was published in 1977 and twenty years later I was still indexing and adding to my documentary files. I remember, in 1965, driving down to Tilbury Docks to collect a crate of microfilms ordered from the U.S. government for this study; the liner that brought the crate has long been scrapped, the dockyard itself levelled to the ground. I suppose I took it all at a far too leisurely pace.

I hope however that this biography, now updated and revised, will outlive its rivals, and that more and more future writers find themselves compelled to consult it for materials that are contained in none of the others. Travelling around the world I have found that it has split the community of academic historians from top to bottom, particularly in the controversy around ‘the Holocaust.’

In Australia alone, students from the universities of New South Wales and Western Australia have told me that there they are penalised for citing Hitler’s War; at the universities of Wollongong and Canberra students are disciplined if they don’t. The biography was required reading for officers at military academies from Sandhurst to West Point, New York, and Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until special-interest groups applied pressure to the commanding officers of those seats of learning; in its time it attracted critical praise from the experts behind the Iron Curtain and from the denizens of the Far Right.

Not everybody was content. As the author of this work I have had my home smashed into by thugs, my family terrorised, my name smeared, my printers firebombed, and myself arrested and deported by tiny, democratic Austria—an illegal act, their courts decided, for which the ministerial culprits were punished; at the behest of disaffected academics and influential citizens, in subsequent years, I was deported from Canada (in 1992), and refused entry to Australia, New Zealand, Italy, South Africa, and other civilised countries around the world (in 1993).

In my absence, internationally affiliated groups circulated letters to librarians, pleading for this book to be taken off their shelves. From time to time copies of these letters were shown to me. A journalist for Time magazine dining with me in New York in 1998 remarked, ‘Before coming over I read the clippings files on you. Until Hitler’s War you couldn’t put a foot wrong, you were the darling of the media; but after it . . .’

I offer no apology for having revised the existing picture of the man. I have tried to accord to him the kind of hearing that he would have got in an English court of law—where the normal rules of evidence apply, but also where a measure of insight is appropriate.

There have been sceptics who questioned whether the heavy reliance on—inevitably angled—private sources is any better as a method of investigation than the more traditional quarries of information. My reply is that we certainly cannot deny the value of private sources altogether. As the Washington Post noted in its review of the first edition in 1977, ‘British historians have always been more objective toward Hitler than either German or American writers.’

2 replies on “Hitler’s war, 1”

I read Irving’s autobio some ten years ago and sadly do not have it anymore.

One essential point was Hitler’s war orientation was almost exclusively designed to create economic autarchy, avoiding the starvation induced by the British blockade in WW1, while providing industry with the raw materials necessary for production.

The books significant addition to the knowledge of WW2 contradicts the insidious attitude that Hitler was a precise aggressor; it rather shows he

reacted to the actions of his foes along the lines of retaining this economic independence.

To wit, the invasion of Norway was a reaction to the British/French plan to land troops in the north and transport them across Sweden to assist Finland resisting the Russian attack in 1940, which was really an attempt to stop Swedish nickle from reaching Germany, an essential mineral for steel production amongst many other necessities. The British also mined Norwegian waters to stop the transport of said materials. If Hitler had not invaded Denmark (the gateway to Norway) or Norway his weapon making capacity would have been crippled.

When Hitler attacked through the Ardennes in 1940, a prime concern was the coal and iron ore resident in Northern France. He did not initially conceive of Manstein’s brilliant plan as the means to conquer France.

When England landed troops and planes in Greece to assist them against the Italian aggression in 1941, an important consideration for Hitler was the security of the Romanian oil at Ploesti, well within range of the Lancaster bombers.

The attack on Russia was also partly promulgated on the defense of the vital oil at Ploesti (Germany’s primary source) as Stalin had stolen Bessarabia from Romania and was within easy striking distance of this .

war-losing lubricant. (In fact, you can Youtube the private conversation between Mannerheim of Finland and Hitler explaining this as one of the requisites for attacking Russia. Hitler further explains that the Wehrmacht had destroyed some 25,000 armored vehicles, all close to the border, and clearly awaiting a signal to attack, the massive force created at the expense of normal economic development through the late twenties and thirties impoverishing the Soviet Union, obviously for Stalin’s plan to conquer Europe.) This was an unimpeachable source unavailable to Irving and demonstrates his and J.P. Taylor’s contention that Hitler did not plan WW2!

Since the attack on the Soviet Union, so often viewed as Hitlers primary strategic mistake, can now be seen as understandable in light of the above facts, the final issue in the ‘Hitler as Warmonger’ diatribe is his Declaration of War on the U.S. I can’t remember Irving’s description of it, apart from Hitler’s anger at the hypocrisy of Roosevelt’s hiding behind ‘Neutrality’ while actively assisting England militarily and the Kriegsmarine’s insistence on fighting the Americans. But I do recall an interview with Goering after the war (though not in Irving’s book) that the German intelligence on America predicted three years before ‘our’ military would be a threat…

Obviously Hitler miscalculated in the extreme. His good friend Putzi Halfstengl had informed Hitler in the ’20’s that Germany could never win any war if America was involved, but Hitler felt wrongly that our country was so troubled by Jews and racial miscegenation that he did not take us seriously – despite the fact we were the cause of Germany’s defeat in WW1. How this otherwise brilliant man could make such an elementary mistake is the most curious fact of modern history …

I think it’s possible that Irving is hated by the mainstream bloc so much because his work is based on independent, original research which can’t be refuted. Since his work can’t be fairly repudiated the man himself had to be attacked and slandered.