N.B. On the fifth of this month, I had said I wouldn’t translate any more passages from my book. But yesterday something happened, which I don’t want to confess, that shook me greatly and encouraged me to translate another passage. Keep in mind that I wrote the first draft of this text a decade before I woke up to the Jewish Question:

______ 卐 ______

Shine: A dad more devastating than Mengele

Shine: A dad more devastating than Mengele

‘Thus, it may well be that the plight of a little child who is abused is even worse and has more serious consequences for society than the plight of an adult in a concentration camp.’

—Alice Miller[1]

Mental illness in the biological sense is a myth. But obviously, insanity isn’t. Insanity exists, but it is a psychological catastrophe, a dysfunction in a person’s ‘software.’

Millions have seen this phenomenon on the big screen. The film Shine was based on the life of David Helfgott, who rose to fame after Geoffrey Rush portrayed his tragic life and won an Oscar for Best Actor. I will sketch his life so briefly that the story will lose its poignancy.

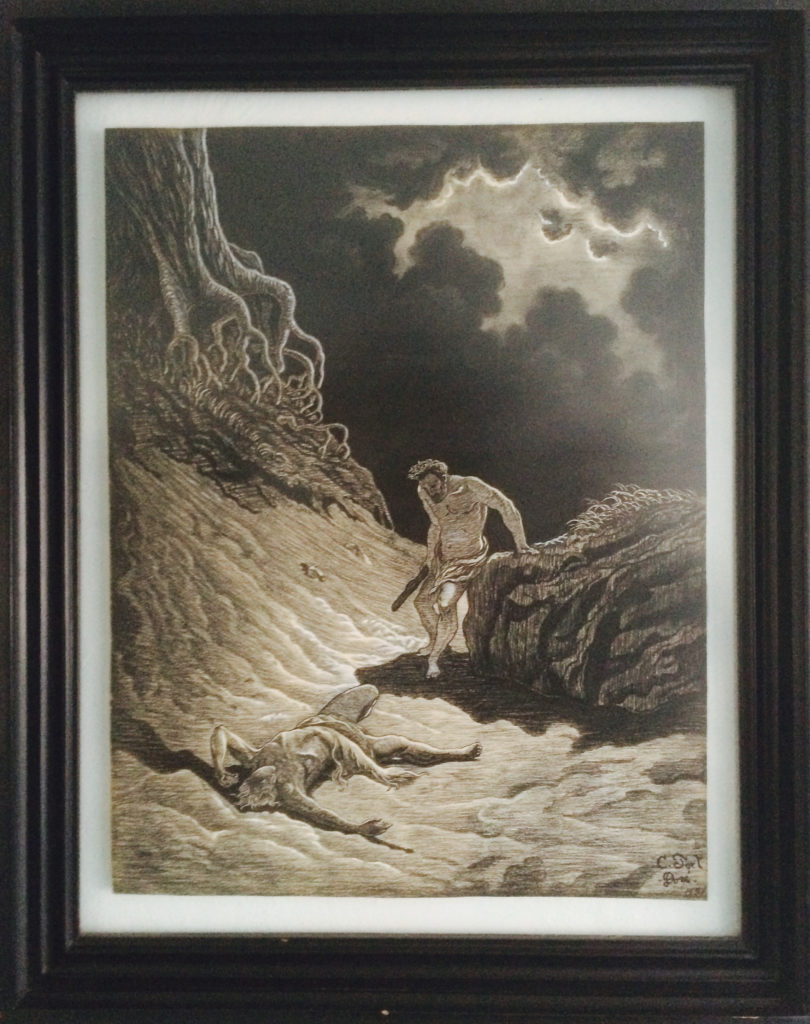

David, a sensitive child with a talent for the piano, was not only Peter Helfgott’s eldest son but also his spiritual heir. He used to run into the street to hug his father when he returned from work, to whom he dedicated his piano career. But Peter did something very wrong. As a child, he had been the victim of terrible humiliation from his own father, Rabbi ‘Djadja,’ as David called his grandfather. Peter’s repressed and buried hatred for Djadja needed an outlet, and he found it in his beloved son, David. The emotional violence toward the boy lasted for years. David was devastated. His story is the story of the murder of a soul.

This is a real-life case. At the time of writing, David Helfgott still lives in Australia and continues to play the piano, although under the care of his wife, Gillian, as he has never fully recovered his sanity. In her biography, Gillian testifies that ‘David always believed’ that his father ‘caused his illness.’[2]

The tragedy of the Helfgott family is a classic example of Theodore Lidz’s ideas, cited in my first book, about a ‘skewed family,’ although in this case the passive role came from the mother. It also exemplifies what Alice Miller has written about how a parent takes revenge on his child for what his own parent had done to him. A new psychology would study parents like Peter instead of treating the brain of the victim of those parents, as psychiatrists do.

Now I would like to mention another real-life case, the young Yakoff Skurnik whom I saw, already an old man, at a presentation of his book in Houston. Based on Yakoff’s testimony, Gene Church wrote one of the most disturbing books I’ve ever read: 80629 (the number is the digit engraved on his forearm).[3] I had seen several documentaries on the subject, but not one about what daily life was like for prisoners, especially Jews, at the Birkenau concentration camp, about two miles from Auschwitz.

Yakoff Skurnik is not only a survivor of the so-called holocaust, where his entire family was murdered, but also of the medical experimentation on children by Josef Mengele. Immobilized by assistants, a doctor named Doering castrated him with minimal spinal anaesthesia. The vivid images of the operation impressed me so much that I had to lie down on the floor for fear of fainting. It is remarkable that Yakoff and other survivors, including other castrated prisoners, were able to rebuild their lives after 1945.

Now, Yakoff didn’t go mad in the concentration camp. But David did with his father. How was that possible? Following the Sullivan-Modrow model, the Nazis somehow encountered greater resistance in reaching Yakoff’s inner self and injuring it than Peter did with his son. A passage by Silvano Arieti sheds some light on these different cases. According to Arieti:

First of all we have to repeat here what we already mentioned […], that conditions of obvious external danger, as in the case of wars, disasters, or other adversities that affect the collectivity [my italics], do not produce the type of anxiety that hurts the inner self and do not themselves favor [insanity]. Even extreme poverty, physical illness, or personal tragedies do not necessarily lead to [insanity] unless they have psychological ramifications that hurt the sense of self.[4]

Studies like Arieti’s were taken seriously in the 1950s, 60s, and even the mid-70s. Although Arieti devoted considerable space to organic studies of madness in his treatise, he revealed that since there was no progress in that model, he never pursued that line of research, but rather, his work ‘will pursue chiefly the psychological approach.’[5] Ideas like Arieti’s were often heard before the giant step backward that psychiatry took when it returned to the 19th-century medical model of treating young people whose egos had suffered an all-out assault by their parents.

But back to what Arieti said. Since the victims of the Nazis were a collective, Yakoff Skurnik’s ego wasn’t assaulted exclusively and to the exclusion of his peers, so they had a better chance of psychological survival than the single victim of parental assault. Arieti wrote:

Even homes broken by death, divorce, or desertion may be less destructive than homes where both parents are alive, live together, and always undermine the child’s conception of himself.[6]

These passages answer one of the favourite arguments of psychiatrists in their attempts to refute the trauma model of mental disorders.

For example, in a critique of his colleagues, psychiatrist August Piper asserts that the claim that childhood trauma causes insanity is fatally flawed. If the claim were true, Piper argues, the years of abuse of millions of children must have caused many cases of insanity. Piper uses as an example the children who suffered unspeakable treatment in ghettos, closed boxcars, and concentration camps in Nazi Germany, adding that despite this abuse, they neither went insane nor dissociated or repressed their traumatic memories. Piper then discusses case studies of those who witnessed the murder of a parent and studies of abducted children. These victims, Piper concludes, neither repressed traumatic events, nor did they forget them or go insane.[7] The case of Yakoff and his companions, who also didn’t go insane, exemplifies what Piper meant.

It is clear that Piper hasn’t read, carefully, the researchers he criticizes. I personally know one of them, Colin Ross, whom I visited in March 1997 at the Ross Institute for Psychological Trauma, a psychiatric clinic north of Dallas. I wrote to Ross because I had read one of his books, and he admitted me to his clinic for a full day as a visiting researcher. In therapy, I saw many women devastated by domestic abuse. Below I quote a passage from a text that, in a thin binder, is given to newly admitted patients:

The problem of attachment to the perpetrator is a term invented by Dr. Ross. It provides a way of understanding the basic conflict in survivors of physical and sexual abuse by parents, relatives, and caretakers. The conflict exists in all of us to some degree, since we all had imperfect parents, but is much more intense and painful in abuse survivors. Ambivalent attachment may not be such a core problem when the perpetrator was not a family member [my italics] or an important attachment figure.

The basic driver of [insanity] is simply the kind of people mom and dad were, and what it was like day in and day out in that family.

The focus of therapy is not on the content of memories, processing of memories as such, or any particular thing that happened. This is because the deepest pain and conflict does not come from any one specific event.

Because children are mammals, they are biologically constructed to attach to their parents. There is no decision to make about attachment. Your biology decides for you and it happens automatically. In a halfway normal, regular family this all works out relatively well with the usual neurotic conflicts. The problem faced by many patients is that they did not grow up in a reasonably healthy, normal family. They grew up in an inconsistent, abusive, and traumatic family. [8]

This is the cardinal distinction that Amara refused to acknowledge in our 1988 meeting when he told me that the thesis of my epistle to my mother ‘was short-sighted.’

The very people to whom the child had to attach for survival, were also abuse perpetrators and hurt him or her badly. One way to cope with the abuse would be to withdraw, shut down one’s attachment system, and go into a cocoon. This would be psychological suicide, and would cause failure to thrive. Your biology will not let you make this decision—the drive to attachment overrides the withdrawal reflex. You must keep your attachment system up and running in order to survive.

The basic conflict, the deepest pain, and the deepest source of symptoms, is the fact that mom and dad’s behavior hurts, did not fit together, and did not make sense. It was crazy and abusive.[9]

What Ross says complements what Arieti said: the person to whom we are vulnerable is the one to whom we have been attached since childhood (at the end of this quintet, I will explain the phenomenon through my relationship with my father). If my summary of Piper’s erudite article could refer to someone like Yakoff Skurnik, the latter could refer to a David Helfgott. Ross speaks of the abusive relationship of a minor with someone who represents something very special to him or her: someone who formed his or her intimate universe. The abuse and crimes Piper speaks of don’t lead to the kind of panic that Modrow and I suffered: the sense of betrayal by the universe.

They are entirely different things.

For example, I have been kidnapped twice in Mexico, a city with one of the highest crime rates in the Americas. Now, I would say that having a machine gun blasting my face during the first kidnapping in 1980, or a gun to my temple for an hour in a car during the second kidnapping in 1992, where they even made me pull down my pants and underwear, didn’t even come close to one percent of the ineffable trauma I felt with my beloved dad’s Jekyll-Hyde transformation, as I describe in the Letter (as David surely felt with his father).

I know what it hurts. I know what hurt me: that the person I loved most and who built my universe betrayed me so inexplicably and sordidly. Neither Piper nor any other psychiatrist can tell me what I felt or has the right to make ‘comparisons’ for the simple reason that they don’t know what they’re talking about.

This is one of the problems not only with psychiatry, but with psychology in general. With their positivist complex of imitating the exact sciences, psychologists aim to objectively study the subject at the level of mere behaviour. This is tantamount to denying that universes of experiences exist within us. It is impossible to study a mind exclusively from the outside: individual testimonies and autobiographies of survivors are lacking. Despite Piper’s erudition—his article has a hundred bibliographical references—his cases have nothing to do with me, Modrow, or David Helfgott. As Robert Godwin wrote in Lloyd deMause’s journal, if your only tool is a hammer, you will treat everything as if it were a nail, and if your only method is ‘empirical science,’ your conclusions are hidden in your method: the self is reduced to another objective fact, no different from rocks or planets.[10] This doesn’t mean I am a dualist. As Ross wrote in The Trauma Model: ‘The trauma model is itself biological. It must be, because in nature, mind and brain are a unified field.’ Recall my software/hardware analogy in the introduction (for a more academic study of the mind-brain relationship, see the work of Roger Penrose).

The Helfgott case answers another favourite argument of biological psychiatrists, an argument that Amara himself used when I was writing the epistle to my mother. He reproached me:

‘The question is why one gets sick and the siblings don’t.’

I still remember Amara’s frank tone when he said that! This was a doctor convinced of the truth of his science, certain that the fact that there are ‘invulnerable siblings’ invalidates any attempt to blame any parent for a child’s emotional downfall. But if there’s one thing I testified to again and again in the epistle, it’s that my parents’ emotional beating was directed almost exclusively at me, not at my siblings: just as Peter’s beating was directed at David, not at his other children; and exactly the same thing can be read in John Modrow’s autobiography.

In my comparison of the Jews David and Yakoff, one victimized by his father, the other by Mengele, there’s something more. The Nazis’ dynamic toward Yakoff didn’t consist of a mixture of cruelty and love like Peter’s toward David—the ‘short circuit’ caused by ‘Jekyll-Hyde’ oscillations I spoke of in the Letter. This dynamic results in an ‘attachment to the perpetrator’ that, according to Ross, is terribly ambivalent. There is a world of difference between being a victim of the Nazis, who appeared in the mind of the Jew Yakoff as strangers, and being a victim of the one who, with all his love, shaped David’s inner universe as a child. In David’s words to his wife: ‘It’s all daddy’s fault. It’s all daddy’s fault […]. ’Cause father had a sort of a devil in him, and an angel in him, and all my life was like that. Dad always had a devil and an angel all his life. It’s a sort of a dichotomy, a split of scale.’ [11]

‘Father’ doesn’t seem to be the same person as ‘Dad’ in poor David’s split mind. That this dichotomy produces splitting was precisely what I saw in the Dallas patients. (My fourth book, The Return of Quetzalcoatl, contains a few pages where I explain in more detail the trauma model underlying Colin Ross’s Dallas clinic.)

Resilience is the ability of an object subjected to stress to recover its size and shape after the deformation caused by that stress. The resilience of elastics is well known: if a rubber band is stretched beyond its point of resilience, it will break and won’t be able to return to its original shape. Based on this comparison, I would say that the assault Yakoff suffered, however infamous, was within the limits of his mental resilience. This was not the case with David. The emotional ordeal he was subjected to exceeded the limit, and he suffered a permanent psychotic breakdown.

In short, the parameter for measuring trauma should be the psychological breakdown resulting from the assault, not the presumed level of the assault for an external observer (like the authors Piper cites). A father who loves his Jewish son can break him more easily than a Nazi who hates Jews. David’s breakdown occurred because Peter’s aggression was relatively greater than that of the Nazis. It came from the least likely source: the one who had formed his soul.

_______________

[1] Miller: For Your Own Good: Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence (Farrar Straus & Giroux), 1985.

[2] Gillian Helfgott and Alissa Tankskaya: Love you to Bits and Pieces (Penguin Books, 1996), p. 268.

[3] Gene Church: 80629: A Mengele Experiment (Route 66 Publishing, 1996). Upon emigrating to the United States, Yakoff Skurnik changed his name to Jack Oran.

[4] Silvano Arieti: Interpretation of schizophrenia (Aronson, 1994), p. 197. I substituted the word ‘schizophrenia’ for ‘insanity’ in the brackets.

[5] Ibid., p. 5. On page 441, Arieti says that, even at that time, there had been no progress in the medical model of madness.

[6] Ibid., p 197.

[7] August Piper Jr., ‘Multiple Personality Disorder: Witchcraft Survives in the Twentieth Century’ in Skeptical Inquirer (May/June 1998). This author is not referring to insanity in general but to so-called ‘multiple personality.’ However, I use the generic word, insanity, because of the problem of comorbidity in psychiatry.

[8] [Colin Ross]: Dissociative Disorders Program: Patient Information Packet (Ross Institute for Psychological Trauma, undated). I haven’t used ellipses between uncited paragraphs.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Robert Godwin, ‘The End of Psychohistory’ in The Journal of Psychohistory, 25:3, 1998.

[11] The two passages separated by the bracket come from Love You to Bits and Pieces (op. cit.), pp. 42 & 104. The relationship between David Helfgott and his father is recounted in chapters 5, 11, 12, 21, 22 and 28.