Below, an abridged translation from the third volume of

Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums.

Interpolations in the New Testament

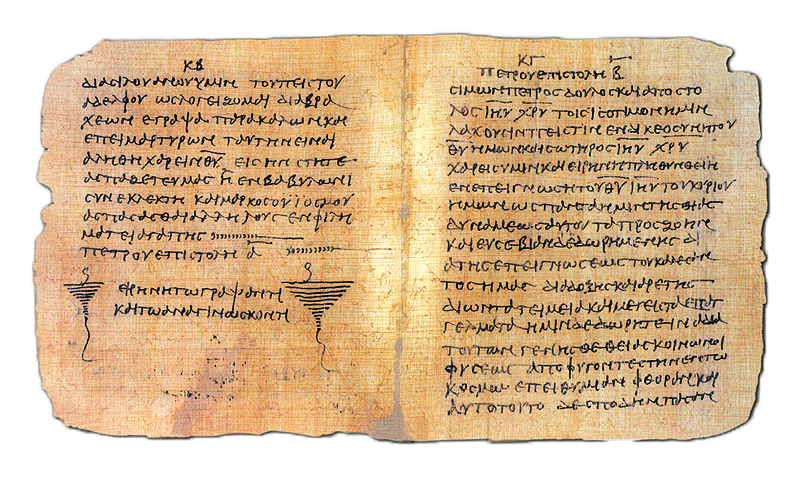

Christians were very fond of interpolations. They have constantly modified, reduced and expanded the New Testament writings and, for that, they had the most diverse motives. They used interpolations, for example, to reinforce the historicity of Jesus or to promote and strengthen certain ideas of faith. Not everyone was able to modify a complete work, but he could easily distort the text of an opponent by introducing or deleting something for his own profit. Falsifications were also done to impose unpopular opinions that the author was not in a position to impose but that, under the name of someone famous, there was a chance to achieve it.

Important authors also fell into this practice. Tatian reviewed Paul’s epistles for aesthetic reasons and Marcion did so for content reasons. Dionysius of Corinth in the 3rd century and Jerome in 4th century complain about the numerous interpolations in the Gospels. But St. Jerome, patron of Catholic faculties and who made ‘the most shameful fabrications and deceptions’ (C. Schneider), accepted the commission of the murderous Pope Damascius to revise the Latin Bibles, of which there was not even two that coincided in somewhat long passages. Scholars have modified the text in some 3,500 places to legitimize the Gospels. And in the 16th century the Council of Trent declared as authentic this Vulgate destined for general diffusion, although the Church had rejected it for several centuries.

Well, in this case it was, so to speak, an intervention of the ‘official’ type. But usually it was produced clandestinely. And one of the most famous interpollations of the New Testament is linked to the dogma of the Trinity that, apart from later additions, the Bible does not proclaim, and for very good reasons.

The classical world knew hundreds of trinities since the 4th century BC. There was a divine Trinity at the top of the world, all the Hellenistic religions had their Trinitarian divinity, there were the dogmas of Trinity of Apis, of Serapis, of Dionysus, there was the Capitoline trinity: Jupiter, Juno and Minerva; there was a thrice-greatest Hermes, the god of the universe three times unique, who was ‘only and three times one’, etc.

But in the first centuries there was no Christian trinity because well into the 3rd century Jesus himself was not even considered as God, and ‘there was hardly anyone’ who thought of the personality of the Holy Spirit, as discreetly ironizes the theologian Harnack. (Except, let’s be fair, the Valentinian Theodotus: a ‘heretic’! He was the first Christian who, by the end of the 2nd century, called the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit a Trinity, something that the Christian tradition still did not dream of.) According to the theologian Weinel, ‘there was rather a revolted mass of ideas about the celestial figures’.

Everything that in Christianity was not pagan comes from the Jews. Another trinity characterised the ‘Holy Scriptures’ in the Revelations of John: God the Father, the seven spirits and Jesus Christ. Soon St. Justin finds a tetralogy: God the Father, the Son, the army of angels and the Holy Spirit. As has been said, ‘a revolted mass’. But little by little, the ancient doctrine—which until the 4th century was widespread even in ecclesiastical circles—, the Christology of the angels, fell into disrepute and was considered heretical. In its place a true dogma was imposed, in addition to all the Christian Churches: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

At last they had the right people all together, but unfortunately not yet in the Bible. Therefore it was fabricated. Fabrication was necessary because in the New Testament there were—and they are—‘false’ opinions, even of Jesus. For example, in the Logion of Matthew 10, 5: ‘Do not go to the nations of the pagans and do not set your foot in the cities of the Samaritans either. Go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel’. From what fate the Greco-Romans would have been spared, and also the Jews, if the Christians had followed these words of Jesus! But for a long time they had done the opposite. In evident contradiction with Matthew 10, 5, the ‘risen’ says right there ‘Go and teach all peoples and baptise them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit…’

At last they had the right people all together, but unfortunately not yet in the Bible. Therefore it was fabricated. Fabrication was necessary because in the New Testament there were—and they are—‘false’ opinions, even of Jesus. For example, in the Logion of Matthew 10, 5: ‘Do not go to the nations of the pagans and do not set your foot in the cities of the Samaritans either. Go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel’. From what fate the Greco-Romans would have been spared, and also the Jews, if the Christians had followed these words of Jesus! But for a long time they had done the opposite. In evident contradiction with Matthew 10, 5, the ‘risen’ says right there ‘Go and teach all peoples and baptise them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit…’

This passage, the mandate of the mission of Christ, is considered true precisely because the Christians soon went on the mission to the pagans: the opposite of the first mandate of Jesus, preach only to the Jews. And to justify this in practice, at the end of the Gospel the mandate to do mission in the wider world is interpolated. And, incidentally, this contained the biblical foundation, the locus classicus, for the Trinity. However, considering that the preaching of Jesus himself lacks the slightest sign of a Trinitarian conception and that none of the apostles was commissioned to baptise, how Jesus, who exhorts to go ‘only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel’ expressly forbids ‘the path toward the pagan peoples’. How could this Jesus ask to do the mission for the world?

The latter mandate, which is increasingly questioned by rationalism, is considered by critical theologians to be a forgery. The ecclesiastical circles introduced it to justify a posteriori both the practice of the mission among the ‘pagans’ and the custom of baptism, and to have an important biblical testimony for the dogma of the Trinity.

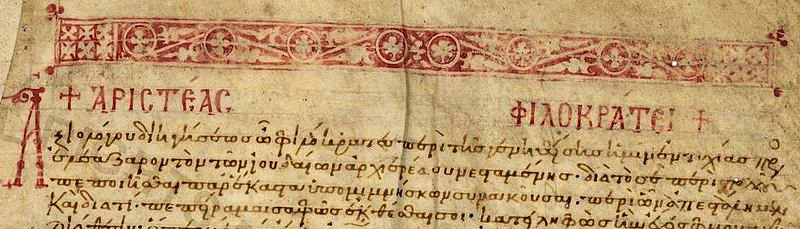

Precisely for that reason in the first epistle of John there was another falsification, minimal in appearance but of special bad reputation, the Johannine Comma.

What was modified was the passage (First Epistle of John 5:7-8): ‘There are three who bear witness: the Spirit, the Water and the Blood, and the three are one’, leaving it as ‘There are three who testify in heaven, the Father and the Word and the Holy Spirit, and the three are one’. The addition is missing in almost all Greek manuscripts and almost all of the old translations.

Before the 4th century, none of the Greek Fathers of the Church used it, nor did they cite it, as a careful verification has pointed out in the writings of Tertullian, Cyprian, Jerome, and Augustine. The fabrication comes from North Africa or Spain, where it appears for the first time about 380. The first to question it was R. Simon in 1689. Today, the exegetes reject it almost with total unanimity. However, on January 13, 1897, a decree of the Roman Office proclaims its authenticity.