by Evropa Soberana [1]

‘But you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for out of you will come a ruler who will shepherd my people Israel’.

—Matthew, 2:6

‘…which you have prepared in the sight of all nations: a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and the glory of your people Israel’.

—Luke 2: 31

‘You worship what you do not know; we worship what we do know, for salvation is from the Jews’.

— John 4:22

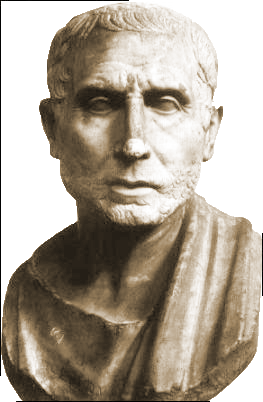

‘Christus, from whom the name [Christians] had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular’.

—Tacitus, Annals, 15: 44, about the persecution decreed by Nero.

Iesvs Nazarenvs Rex Ivdaeorvm

Yosef (a.k.a. Joseph), Jesus’ father, was a Jew from the House of David. But since Yosef supposedly did not intervene in the Virgin’s pregnancy, we will go on to examine the lineage of Miriam (a.k.a. Mary).

Luke the Evangelist was an individual from Antioch, in present-day Turkey. According to him, this woman was from the family of David and the tribe of Judah, and the angel who appeared to her predicted that a son would be born to whom Jehovah ‘will give him the throne of David, his father, and he will reign in the house of Jacob’.

According to the gospel story, Jesus was born in Bethlehem. In the Gospel of Matthew (1: 1) he is associated with Abraham and David, and in that same gospel (21: 9) it is described how the Jewish crowds in Jerusalem acclaim Jesus by shouting ‘Hosanna to the Son of David!’ without mentioning, of course, the ‘wizards of the East’ who visited the Messiah by following a star and asking ‘Where is the king of the Jews who was born?’ (Matthew, 2: 1-2).

Jesus, who never intended to found a new religion but to preserve pure the Orthodox Judaism made it clear, ‘I have not come to repeal the Law [of Moses, the Torah] but to fulfil it’ and, enraged to see that the Jerusalem temple was being desecrated by merchants, he threw them with blows. This Jewish agitator, like an Ayatollah, did not hesitate to face—with the authority given to him by being called rabbi—the other Jewish factions of his time, especially the Sadducees.[2]

Jesus surrounded himself with a circle of disciples among whom we could highlight the mentioned Simon the Zealot, Bartholomew (of whom Jesus himself says in the Gospel of John, where he is called Nathanael, ‘here is a true Israelite’); Judas Iscariot (who betrayed him to the Sadducees for money), Peter, John and Matthew.[3] Although there is not much information about the rest of the Apostles, it is necessary to remember that, until the trip of Paul (also Jewish) to Damascus after the death of Jesus, in order to be a Christian it was essential to be a circumcised, orthodox and observant Jew.

That the doctrine of Jesus was addressed to the Jews is evident in Matt. 10:6, when he says to the twelve apostles: ‘Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel’. The phrase implies to rescue those Jews who have strayed from the Law of Moses. This was because ‘if you believed in Moses you would believe me’ (John, 5:46).

In the year 26, Tiberius, who had expelled the Jews from Rome seven years before in times when the zeitgeist was fully anti-Semitic, appointed Pontius Pilate as a procurator of Judea, a Spaniard born in Tarragona or Astorga: the only decent character of the New Testament according to Nietzsche.

After the incident with the banners of Pompey, the Jews had obtained from previous emperors the promise not to enter Jerusalem with the displayed banners, but Pilate enters parading in the city, showing high the standards with the image of the emperor. This, the golden shields placed in the residence of the governor, and the use of the money of the temple to construct an aqueduct for Jerusalem (that transported water from a distance of 40 km), provoked an angry Jewish reaction. To suppress the insurrection, Pilate infiltrated the soldiers among the crowds and, when he visited the city, gave a signal for the infiltrated legionaries to take out the swords and start a carnage.

In the year 33, after various skirmishes of the Jesus gang with rival factions—particularly with the Sadducees, who at that time held religious power and saw with discomfort how a new vigorous faction arose—, Pontius Pilate orders the punishment of Jesus, at the request of the Sadducees. Jesus is scourged and the Roman legionaries, who must have had a somewhat macabre sense of humour and who knew that Yeshua proclaimed himself Messiah, put a crown of thorns and a reed in his right hand, and shout at him with sarcasm ‘Hail, king of the Jews!’ (Matthew 27: 26-31 and Mark 15: 15-20). When they crucified him they placed the inscription I.N.R.I. at the top of the cross: IESVS NAZARENVS REX IVDAEORVM (Jesus Nazarene King of the Jews).

Yeshua of Nazareth, known to posterity as Jesus, was one of many Jewish agitators who were in Judea during the turbulent Roman occupation. Executed around the year 33 during the reign of Tiberius, his figure would be taken by Saul of Tarsus (a.k.a. Paul): a Jewish Pharisee marvelled at the power of subversion that enclosed the sect founded by Jesus.

Jesus was, then, one of many Jewish preachers who, before him and after him, proclaimed themselves Messiah. Only that, in his case, Saul of Tarsus (now Turkey) would soon call him, instead of masiah, Christus: the Greek equivalent of ‘Messiah’. After changing his name to Paul he preached the figure of ‘Christ’, indissolubly linked to the rebellion against Rome, throughout the empire, deciding that Christianity should be spread out of its narrow Jewish circle and introduced in Rome.

________________

[1] Slightly modified by the Editor of this site.

[2] Note of the Ed.: The split of early Christianity and Judaism took place during the first century CE. Traditional Christian doctrine aside, it is more likely that the point of conflict between Jesus and the religious authorities was political rather than religious. It had its roots right after the driving of the traders from the Temple of Jerusalem. Jesus thus came into direct conflict with the High Priest, a Sadducee: the one who officiated the Temple.

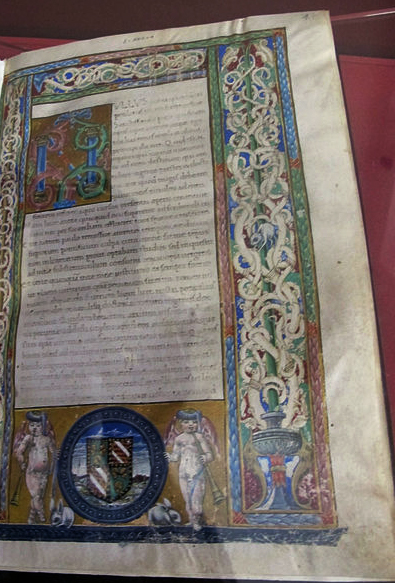

The texts known as the ‘New Testament’, written not in Jesus’ Aramaic but in Greek, are Christian propaganda when, later, the early church entered in conflict with the Pharisees. (At the time that the gospels were edited the Sadducees had lost their leadership and the Pharisees were the sole repository of religious authority.) Although the evangelists specifically mention the Pharisees as those who Jesus scolds—even the author of this essay (which is why I modified his text)—, modern scholars postulate that the fight of the historical Jesus was with the Sadducee faction of Judaism: the bourgoise priesthood that represented the Temple, the collaborators with Rome.

On the other hand Talmudic Judaism, as known today, is the offshoot of Pharisee theology with Jews already in the Diaspora.

No Sadducee documents survived Titus’ conquest of Jerusalem. It is likely that, by editorial intervention, the name ‘Pharisees’ was substituted for the original ‘Sadducees’ in several gospel verses, in times that early Christians clashed with the Pharisees. In future instalments of the Kriminalgeschichte series (Volume III) we will see the extent of the tampering of gospel verses by the early Church.

[3] Note of the Ed.: Not to be confused with Matthew the Evangelist, a Greek-speaking author who never met Jesus in the flesh.