Our times are as decadent as the 4th century Rome of the Common Era, an age of treason that dragged our civilization straight into a dark night of the soul that lasted a millennium.

Tom Sunic is surely right in inviting would-be nationalists to become familiar with literature that balances the purely left-hemisphere, intellectual approaches to our western malaise.

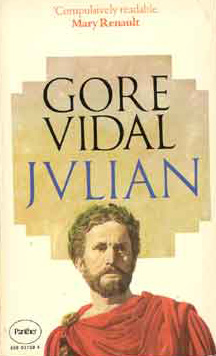

The best historical novels ever written are Gore Vidal’s Julian (1964) and Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980), which cover the gap that my high school skipped over: the zeitgeist of the peoples during Christendom, with Vidal covering its origins when the “Galileans” conquered state power to advance their cult, and Eco its apex in the fourteenth century.

The best historical novels ever written are Gore Vidal’s Julian (1964) and Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (1980), which cover the gap that my high school skipped over: the zeitgeist of the peoples during Christendom, with Vidal covering its origins when the “Galileans” conquered state power to advance their cult, and Eco its apex in the fourteenth century.

This is my translation of what I wrote in the novel’s blank pages by the end of 1991, when I read a magnificent, hardcover English-Spanish translation of Julian that my girlfriend gave me as a present in Barcelona.

With pencil I wrote:

Now that I read the book, its antichristian message surprised me. What did the book-reviewers could have said?

I would feel appalled to know if the assassination of Julian was historical. I’ll have to check it out…

But the antichristian message of the last pages represents the moral of the story: the first clearly antichristian novel that I know. I wish that Kubrick makes a film of it instead of his dream about a Napoleon movie.

If I interpret the novel correctly, the emergent Christian authoritarianism was the storms harvested after the sowing of winds (the Roman state had persecuted the Christians before). But what makes me furious is that there were no groups that defended Hellenism with their teeth and nails!

What impressed me the most about the book is that it really makes one hate the Christians. I wish it had been published in those times! However, if the assassination of Julian by a fanatic Christian was not historical, Vidal could be accused of fabricating facts in search for drama. This is the most important event of my reading. I’ll find out next Monday when they open the library or perhaps even write the author.

I did go to the library and wrote to Vidal two decades ago but did not receive an answer. According to the Wikipedia article of today, the novel is historically accurate.

I wish I could know whether other assertions of the novel were historical. For example, Vidal makes Julian say in a specific moment (I only have the Spanish translation that Anabel gave me, so I can’t quote the original text) that “thirty years ago” Rome’s archives contained several contemporary reports about Jesus’ life, but they disappeared, destroyed by instructions from Constantine.

But the real climax of the novel are the words of Libanius, telling to himself in painful soliloquy after his most beloved, young disciple deserted him after converting to Judeochristianity that no invention from man can last forever, not even Christ: man’s most noxious invention.

Libanius was a historical figure, the one who claimed that Julian had been assassinated by a Christian. The novel ends with an aged Libanius feeling utterly alone in a world gone mad, telling silently to himself in the solitude of his study that the light of the world was gone with Julian, the last hope for our civilization; and that there was nothing left but let the darkness fall on the West and await for a new sun. A new day. In the future…