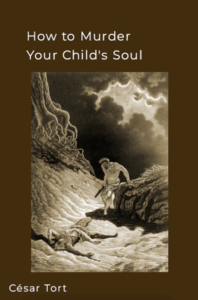

Apparently, some visitors to this site don’t even know what child or adolescent abuse is. This prompts me to publish below the final pages of my book. I refer to the pages preceding the appendices:

How to murder your child’s soul

– with the help of a psychiatrist –

First, marry a man who is super-affectionate with children: someone who has an extraordinary graceful charm with them and whom you can also manipulate.

First, marry a man who is super-affectionate with children: someone who has an extraordinary graceful charm with them and whom you can also manipulate.

Second, narcissistic mother, you must understand that your child is a part of your mind. His thoughts, feelings and desires are your private property: they are part of your inheritance. His emerging mind is like a computer and you have the duty and the right to program it as you please.

Any initiative, natural spontaneity or free will of the child that doesn’t reflect your programming is a symptom of mental illness, so you must harass him mercilessly.

If, upon reaching puberty, he rebels against your possessive behaviour, go to your husband. He is stronger than the boy, and if you use your feminine wiles to have your husband publicly humiliate him with tremendous slaps across his little face, all the better. The harder the overly affectionate father hits him, the greater the trauma will be. The goal is to provoke a monstrous confusion of feelings: that the one who gave him the most love as a child will be the one who shows him the greatest hatred as a teen…

This is the key to murdering your child’s soul, and if your husband fails to develop the gift of lycanthropy, you may not achieve your objectives. Remember that nothing undermines more the sensitive and developing mind of a child or teenager who adores his dad than these inexplicable changes.

If, even with these measures, you haven’t reached his inner self to injure it, seek the services of a specialist! A psychiatrist or psychoanalyst will do a good job. Your son will be forced to attend sessions at the Ministry of Love…

Since he is already in a state of shock and trauma from the insults and beatings from his beloved dad, you will have a golden opportunity to, precisely at that moment of maximum vulnerability victimize him again to produce irreversible psychological damage. If you also choose a professional with gentle manners and media fame, no one will suspect a thing about the drastic measure you’ve taken.

If, in O’Brien’s therapy, your child suffers panic attacks and develops delusions (‘mum wants to possess my thoughts,’ ‘my father is turning into Mr. Hyde,’ ‘a doctor they hired wants to poison me with drugs’) don’t go thinking these are echoes of your splendid upbringing or the medical attack. The therapist will inform you that under no circumstances should the parents be blamed for the child’s emotional disturbance. Quite the contrary: the evidence of a biological defect in your kid is irrefutable. This wise man in a white coat has a Malleus Maleficarum DSM where he will easily find the name of his ailment. Once diagnosed, his prescription will be to bombard the deluded brat with the most incisive neuroleptic. The resulting panic attacks, dystonia and akathisia—all effects of the drug—will be more than enough to control him. Akathisia is hellish: and people will think the crises are your sick child’s doing, not the drug you secretly slip into his food.

But make sure he doesn’t get away with it and avoids a chemical lobotomy. You wouldn’t want him to write an autobiography when he’s grown! On the other hand, if he takes his meds he’ll be as docile as a lamb and he’ll never be able to say what you, your husband and the psychiatrist did to him.

Then you’ll have the beloved little child of your dreams. You’ll be able to dress him, feed him and, given his irreversible tardive dyskinesia, change his diapers.

And remember: you have your husband, the medical establishment and the whole of society on your side…