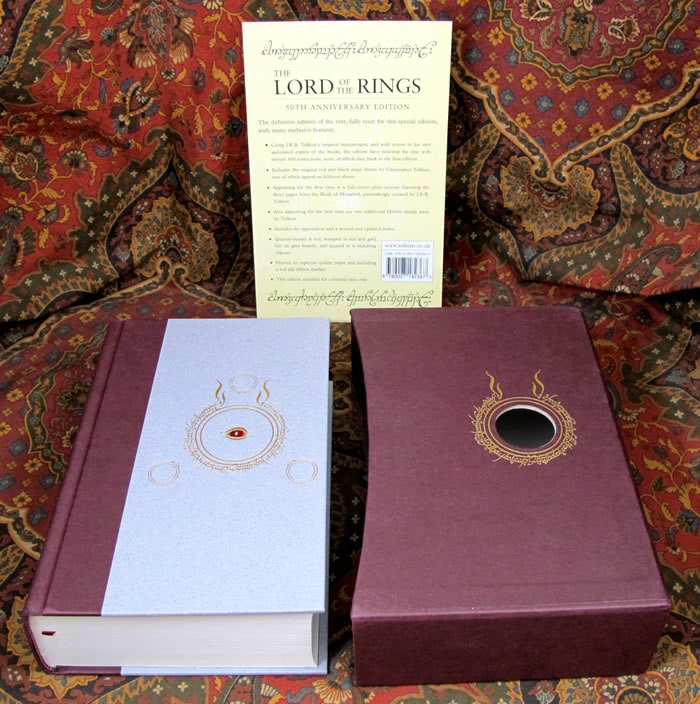

In a one-volume edition celebrating the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s book, I read The Lord of the Rings from March 2011 to February 2012, while listening to the audio of LOTR voiced by Rob Inglis.

I must say that since I wanted to be a film director, I think that only the first film of Peter Jackson’s adaptation was good. The other two suffer from the typical stridency of Hollywood in recent decades, especially the extended battle scenes. Tolkien’s novel has no stridency. On the contrary: it has a very slow development. And what is most striking are his descriptions of the countryside: something that those of us who live in large cities have completely lost and must recover if, after destroying the ring, return to the Shire.

I must say that since I wanted to be a film director, I think that only the first film of Peter Jackson’s adaptation was good. The other two suffer from the typical stridency of Hollywood in recent decades, especially the extended battle scenes. Tolkien’s novel has no stridency. On the contrary: it has a very slow development. And what is most striking are his descriptions of the countryside: something that those of us who live in large cities have completely lost and must recover if, after destroying the ring, return to the Shire.

But that doesn’t mean that I loved LOTR. I think it’s a children’s tale, not even a teenager’s, which is noted in a passage where King Théoden, once Gandalf broke his spell, spares Wormtongue’s life instead of killing him. (For having spared his life, Wormtongue later conspired with Saruman to exterminate the people of Rohan.)

I confess that this passage irritated me a lot, both in the film and in the novel; and we can only forgive it if we read LOTR to our little children, night after night, until the book is finished. But the problem I see with contemporary Aryan man is his long childhood. A Viking teenager wouldn’t have even understood why sparing the life of a Jew-like character who would only bring enormous evil to the kingdom.

When I finished reading LOTR I wrote: ‘What I say in El Retorno de Quetzalcóatl about Don Quixote by Cervantes compared to Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s book applies here: It talks ill of Westerners and Englishmen who have this work (fiction) at the top and know nothing about the Führer’s actual words—history, epic, and real tragedy—in the book I’m reading and will use in my next entry, “Hitler on Christianity”. An edition of such luxury [that of LOTR] for his talks should incorporate a very long prologue by David Irving’.

In that soliloquy, I wanted to tell myself that just as it bothered me that Spanish speakers preferred to read Cervantes’s fiction rather than Diaz’s non-fiction about the conquest of Mexico, it also bothered me that English-speakers preferred Tolkien’s fiction to Irving’s non-fiction. Having said this, the words of LOTR in which I projected myself were:

‘I wish it need not have happened in my time’, said Frodo.

‘So do I’, said Gandalf, ‘and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us’.

I had already collected it as a quotable quote. I also liked: ‘It was an evil fate. But he [Frodo] had taken it on himself’ (page 644). I projected myself even more in some words that in Jackson’s version appear at the end, when Frodo writes LOTR and says in soliloquy that there are such wounds that it is no longer possible to bear them.

All in all, I wouldn’t recommend LOTR to young people as what we need are real-life stories that inspire them, like the lives of Leonidas and Hermann. Movies and TV series about them and Hitler are missing from the point of view of the fourteen words.

When in the past century I lived in Manchester a native English man invited me on a peripatetic outing to the countryside with others and I am ashamed to say that I declined the invitation. Yes, I would recommend LOTR to those who want to get out of the monstrosity that Saruman did with his arboreal destruction, iron industry and multiplication of Orcs—a symbol of the soulless London—and want to reconnect with Nature (bucolic England).

If I were a film director and wanted to make a children’s movie, I would bring LOTR to the screen by retrieving all those detailed descriptions of the field in Tolkien’s prose.

4 replies on “On LOTR”

Julius Caesar spared the life of Brutus after Brutus had betrayed him, and he even adopted Brutus as his son.

Wrong example. Precisely because white advocates refuse to read non-fiction authored by anti-Christians (like Pierce’s story), they ignore that Brutus was the good guy and Caesar the bad guy who betrayed the Republic.

Preservationoffire.com

Ash Donaldson is doing just this, creating new stories and myths for adults and children. Please look at them.

‘Yes, we will have peace,’ he [Théoden] said, now in a clear voice, ‘we will have peace, when you and all your works have perished – and the works of your dark master to whom you would deliver us. You are a liar, Saruman, and a corrupter of men’s hearts. You hold out your hand to me, and I perceive only a finger of the claw of Mordor. Cruel and cold! Even if your war on me was just – as it was not, for were you ten times as wise you would have no right to rule me and mine for your own profit as you desired – even so, what will you say of your torches in Westfold and the children that lie dead there? […] When you hang from a gibbet at your window for the sport of your own crows, I will have peace with you and Orthanc. […] A lesser son of great sires am I, but I do not need to lick your fingers. Turn elsewither. But I fear your voice has lost its charm.’

J.R.R. Tolkien – The Lord of the Rings, The Voice of Saruman