Without the wisdom of Irmin Vinson on the subject of the Holocaust (see e.g., here and here) no nationalist will ever reach intellectual maturity. “Spielberg & the eleven million” is only the latest of his articles at Counter-Currents:

“The Holocaust has increasingly become, for the democratic world at least, a symbol of all the other Genocides, for racism, anti-Semitism, hatred of foreigners, ethnic cleansing, and mass destruction of humans by humans generally. The reason for this is, possibly, that a vague realization is taking hold of people that the Holocaust, the planned total annihilation of the Jewish people at the hands of the Nazi regime, is both a Genocide like other Genocides, and also an unprecedented event in human history, which should serve as a warning to all of us.” — Prof. Yehuda Bauer, Yad Vashem

In an episode of Steven Spielberg’s miniseries Band of Brothers (2001) American soldiers, the men of Easy Company, stumble upon a German concentration camp, a satellite of Dachau, where to their horror they discover hundreds of emaciated Jews, along with about an equal number of Jewish corpses. It is the spring of 1945 and we are — or so Spielberg would have us believe — in the midst of an extermination facility, one part of the vast industrialized machinery of mass murder designed to effect the nazi Final Solution, the physical extermination of the Jewish people. All of the inmates in the camp are thus Jews, identified by the yellow stars stitched into their striped camp uniforms, and they identify themselves as Jews to the startled liberators.

That was Spielberg’s first inaccuracy, which we shall call Falsehood #1. Most of the inmates at Dachau and Buchenwald, about eighty percent, were non-Jews. When we look at photographs of liberated German concentration camps, we now think that all of the “survivors” we see are Jews. But that, as a matter of uncontested fact, is untrue. In 1945 American media coverage of the liberation of the camps on German soil rarely spoke of Jews, for the simple reason that Jews were a minority among their various inmates. The Americans who liberated the camps did not “confront the (Jewish) Holocaust,” as Spielberg’s Band of Brothers wants us to assume. They instead discovered, as a contemporary British documentary put it, “men of every European nationality, including … Germans.”

Falsehood #1 — the ejection of Gentiles from Dachau and their replacement with Jews — generates a problem for Spielberg. If all of the inmates in the concentration camp presented in Band of Brothers are Jews, and if Hitler wanted to exterminate all Jews, then why are the inmates still alive? That is also, of course, the monumental problem that the Jewish Holocaust has always faced. Why did the Germans fail to kill all the Jews under their control? Why did they bother to evacuate Jewish internees from the East? Why is Elie Wiesel, evacuated in 1945 from Auschwitz in Poland to Buchenwald in Germany, still alive? Why was Anne Frank not gassed at Auschwitz? Why was she instead relocated to Bergen-Belsen, where she tragically succumbed to typhus?

By falsely making all of his camp’s inmates Jews, Spielberg faces the same problem, and he invents a solution — Falsehood #2. The camp guards, a Jewish survivor tells Spielberg’s American liberators, desperately shot as many of the inmates as they could, knowing that the imminent arrival of Allied liberators would end their genocidal mission. Then they ran out of ammunition. So they fled, no doubt disappointed at their failure to implement fully their part of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question. They had killed as many Jews as they were able to kill, but not as many Jews as they had wanted to kill (i.e. all of them, every single person in the camp). The emaciated Jews we see on the screen are still alive because the nazi killers fortuitously ran out of bullets.

Liberation of Dachau, 29 April 1945: In photographs of concentration camps we now see Jews, but in fact the men above are Poles.

Even for most mainstream Holocaust scholarship, the presence of survivors at Dachau poses no insurmountable problem, since the bulk of the inmates interned there were not Jewish. We should keep that significant yet often overlooked fact in mind: In 1945 none of the American liberators of German concentration camps believed that they had uncovered the physical machinery of a plan to murder all Jews, because the majority by far of the inmates they liberated were Gentiles.

A mainstream historian today can account for living men and women in Dachau even if he accepts the proposition that NS Germany planned the extermination of all Jews. A revisionist historian, who denies that NS Germany planned the extermination of all Jews, can also (and much more plausibly) account for Jewish survivors in the German camps: Hitler did not attempt to murder every Jew on the face of the planet, and the survival of the twenty percent of the inmates at Dachau and Buchenwald who were indeed Jewish proves it. If Hitler had wanted them dead, and if exterminating Jews was the central motive of his political career, they all would have been killed long before the Allies arrived. The Jewish survivors in the various camps therefore prove the revisionist thesis.

Falsehood #1, which amounts to the judaizing of Dachau, is necessary for Spielberg, because it preserves the concentration camp as distinctively Jewish symbolic territory. Spielberg, who rediscovered his Jewishness after studying the Holocaust, has no intention of commemorating German crimes by depicting non-Jews as the majority of the victims. He wants to retain the potently Jewish symbolism of a concentration camp, established in public consciousness by hundreds of Holocaust films and Holocaust memorials, and he is willing to ignore factual history to achieve his political aims. Falsehood #2 — the claim that Germans tried to exterminate Dachau’s inmates — is also necessary for Spielberg, because without it the death camp presented on our television screens would be reduced to an internment camp or even to a mere prison, ceasing to appear as a site for genocide. A nazi concentration camp not dedicated to genocidal mass killing would be a contradiction in terms.

We are thus prepared for Falsehood #3, which is the ideological culmination of the others. A final notice, which brings this episode of Band of Brothers to its conclusion, reads: “During the following months, Allied Forces discovered numerous POW, concentration, and death camps. These camps were part of the Nazi attempt to effect the ‘Final Solution’ to the ‘Jewish Question’. Between 1942 and 1945 five million ethnic minorities and six million Jews were murdered — many of them in the camps.”

Falsehood #3 — the “five million ethnic minorities” — is more complex than its two predecessors and requires a longer explanation.

In popular memory the Holocaust is the extermination of Six Million Jews. Any man on the street asked to put a numerical figure to the Holocaust’s victims will have a simple answer: Six Million. Yet at a more official level the Holocaust is really the extermination of Eleven Million: Six Million Jews plus five million “others,” even though those “others” are generally absent from the Holocaust’s public representations.

Many Holocaust museums, including the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, are officially dedicated to the Eleven Million. Unsurprisingly the Jews running the USHMM have blithely ignored an explicit mandate to that effect, secure in the knowledge that no politician would dare complain that the Museum is too Jewish and should diversify itself by sharing almost half its space with five million dead Gentiles. In theory, however, about half of the Holocaust is non-Jewish, and if the Holocaust were an affirmative-action employer, about half of all the Holocaust films and Holocaust museums and Holocaust educational programs would be devoted to non-Jews.

In Band of Brothers Spielberg elects, as an act of multicultural inclusion, to present the Holocaust as the extermination of the Eleven Million, not simply of the Six Million, because he wants to construct Dachau as an unmistakable embodiment of “racism.” He wants us to believe that Germans murdered, in camps like Dachau and elsewhere, Six Million Jews and five million other minorities as part of their deranged racial vision of the world, which required the physical extermination of various non-optimal racial types, not only Jews.

The liberation episode in Band of Brothers is thus appropriately entitled “Why We Fight,” indicating that the Americans who liberated the camps belatedly discovered an “anti-racist” justification for World War II in their horrific “confrontation with the Holocaust.” A White American in 1940 might not have known what “racism” could lead to — he might even have been a “racist” himself — but after he saw “racism” concretized in the camps in 1945, he knew what he had been unwittingly fighting to prevent. That, at any rate, is the lesson Spielberg hopes we will learn.

This formally inclusive anti-racism also provides an official rationale for the presence of the USHMM on the Mall in Washington, at the symbolic heart of American nationhood: “This museum belongs at the center of American life because America, as a democratic civilization, is the enemy of racism and its ultimate expression, genocide.” The Eleven Million are a more ecumenical and democratic statement of anti-racism than the Six Million, and they imply that not only Jews have a stake in the institutionalized commemoration of Jewish deaths.

The five million others are always dispensable, but they are, despite their virtual absence from public view, structurally useful to the Holocaust when it provides anti-racist lessons to multiracial America, because they prove that Holocaust commemoration is not simply a self-serving warning against the evils of anti-Semitism. If you think of yourself as a racial or an ethnic minority, then you too are included in the Holocaust, even though you may find yourself relegated to a few footnotes or (as in this case) to a single line at the conclusion of a television program that has otherwise deliberately excluded you.

Spielberg could have accomplished his educational objective by eliminating Falsehood #1 while retaining Falsehood #2. In other words, he could have visibly embodied the Eleven Million in a throng of emaciated European “ethnic minorities” milling about the camp awaiting liberation, with a few Jews wearing yellow stars sprinkled among them. Falsehood #2 could have been spoken by (say) a Pole or a Serb, a non-Jewish minority, a member of one of the ethnic groups whose victims (allegedly) comprise the five million.

Although Polish Holocaust survivors in speaking roles are likely too WASPish for the purposes of contemporary anti-racism, and although Jews hate Poles even more than they hate Germans, their visible presence would be a reasonable concession to the historical fact that most of the inmates at Dachau were Gentiles, many of them Poles and Catholics.

Band of Brothers would have remained, even with this gesture to multiethnic inclusion, an ideologically driven fiction, still falsely presenting Dachau as a place where Germans warehoused minorities whom they planned (when time and available ammunition permitted) to murder; yet it would have been spared the burden of one theoretically unnecessary lie, the lie that Dachau was filled with Jews.

Spielberg is not, however, interested in anti-racism alone, so the lie was politically imperative. He, like most Holocaust promoters, has little interest in generic anti-racism. He prefers a special kind of anti-racism, a Judeocentric anti-racism wherein his Jewish minority can stand for other minorities, whose literal presence then becomes optional. The Holocaust can be reduced to the Six Million in most public presentations, or enlarged (for the sake of multicultural inclusion) into the Eleven Million whenever Jews think it expedient.

Jews have successfully figured Jewish Holocaust survivors and Jewish Holocaust deaths into synecdoches for the results of “racism,” one part standing for the rest, so that other victims become semantically superfluous and need not be exhibited. It is a politically valuable symbolic structure that no activist Jew would willingly endanger, and hordes of White Holocaust survivors in a didactic version of Dachau are thus unthinkable.

This flexible structure has important practical consequences. A student being indoctrinated into the truths of multiracialism can learn his anti-racist lessons while contemplating only the Six Million, which is the normal educational practice in most Holocaust museums. “Because of its Jewish specificity,” Yad Vashem’s Avner Shalev argues, “[the Holocaust] should serve as a model in the global fight against the dangers of racism, anti-Semitism, ethnic hatred and genocide.” Jewish specificity is somehow equivalent to human universality, so through the symbolic magic of the Holocaust we can commemorate crimes against any given minority by commemorating German crimes against Jews.

If a Euro-American wants to rid himself of “racism” and learn tolerance for Blacks, he need only study German atrocities against Jehovah’s Chosen People, whose victims during the Holocaust serve, in the words of philosopher Paul Ricoeur, as “delegates to our memory of all the victims of history.” As the result of a process purportedly involving nothing extrinsic to the events of the Holocaust, nothing so vulgar as Jewish media power, Jewish Holocaust victims have come to signify all other racial victims from time immemorial down to the present.

Spielberg therefore presents the Eleven Million while dispensing with all visible evidence of any victims other than Jewish victims, a prerogative that the Holocaust entitles him to exercise. Indeed he gains the best of both worlds: He explicitly states the Eleven Million, signaling multicultural inclusion, while eradicating all Gentile camp inmates from the screen. His wildly unhistorical version of Dachau is an exact duplication of the ideological structure of an anti-racist Holocaust museum: Jewish victims stand for all other victims.

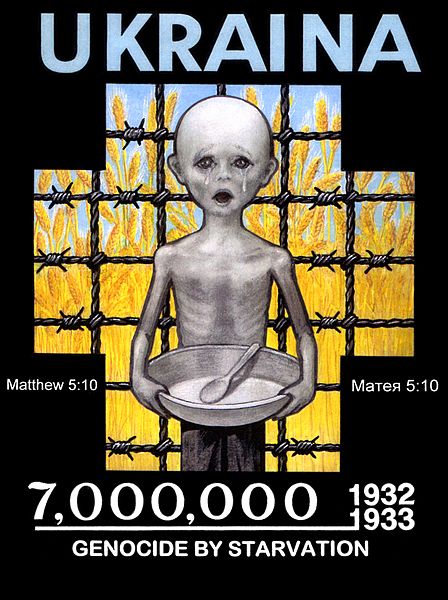

Yet in fact — and here we enter into the strange complexity of the Eleven Million — Spielberg’s multicultural deference to the five million others, Falsehood #3, is more historically inaccurate than his racial devotion to the Six Million Jews. For the Eleven Million are bogus, pure fantasy. If the five million others who form the Holocaust’s Gentile Auxiliary include all Allied civilians who died during the course of the war, the figure is far too low; if it means (as Spielberg intends) targeted ethnic minorities who perished in German concentration camps, it is far too high. (See Peter Novick, The Holocaust in American Life [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999], 215–216.)

Although revisionists seek to reduce the Six Million to some smaller number, it remains a genuine result of mainstream scholarship, whether it is true or not. No revisionist, furthermore, denies that millions of Jews were killed by Germans or died in German concentration camps. The five million, on the other hand, are completely fictional and no Holocaust scholarship could ever account for their official recognition as co-victims with the Six. They were conjured up, on the basis of political expediency alone, by nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal in order to provide an emotional reason for non-Jews to commemorate the Holocaust, while retaining preeminent Jewish victimhood.

Five million dead Gentiles are simply one million victims fewer than Six Million dead Jews, and that elementary arithmetic is literally the source of the Eleven Million victims that the Holocaust is officially supposed to commemorate, an obligation honored more in the breach than the observance. So by paying occasional lip service to the five million, Jews are falsifying history; by regularly ignoring them, they are unintentionally respecting the historical record.

Since most Americans have probably never heard of the five million, who constitute only a small part of the Holocaust’s public mythology, we should not exaggerate their political significance. It is, however, worth noting the symbolic instability of this five million. Insofar as the five million are Gentiles they are us, our stake in the Jewish Holocaust, invented as a motive for our commemoration; insofar as they are “ethnic minorities” they are Other, not us, essentially surrogates for rainbow-coalition minorities, who can thereby be transported back into wartime history to teach anti-racist lessons.

In the five million we are supposed not only to see ourselves but also to see the potential victims our of “racism,” our reason for avoiding nazi-like racial self-assertion. A nonracialized interpretation of the five million would be useless for Holocaust lessons in racial tolerance; a five million comprised of powerless “ethnic minorities” provides an appropriate supplement to Judeocentric anti-racism.

Tens of millions of European deaths occurred in World War II, together with an incalculable number of casualties. Through Holocaust arithmetic they have all dwindled into one million less than Six Million, reduced to a symbolically ambiguous cohort of token Gentiles that Jews rarely even deign to exploit.

____________

See endnotes at the original article in Counter-Currents.