Die ersten unterdrückerischen Gesetze gegen das Heidentum wurden von Kon-stantin erlassen. Im Jahr 331 erließ er ein Edikt, das die Beschlagnahmung von Tempelbesitz legalisierte. Damit bereicherte er die Kirchenkassen und schmückte seine Stadt Konstantinopel. Er leitete städtische Gelder von den Kurien an die kaiser-liche Schatzkammer um. Die Kurie verwendete diese Mittel für den Bau und die Re-novierung von Tempeln sowie für heidnische Bankette, Prozessionen und Feste. Durch die Umwidmung der städtischen Mittel wurde der Einfluss des Heidentums im öffentlichen Raum deutlich verringert. Auch bei der Auswahl von Kandidaten für Regierungsämter bevorzugte Konstantin die Christen. Zum ersten Mal in der Ge-schichte des Reiches wurde der Übertritt zum Christentum als attraktives Angebot betrachtet.

Die ersten heidnischen Tempel und Statuen wurden unter Konstantin vandali-siert und zerstört. Die Christen glaubten, dass diese erste Welle des Bildersturms der Erfüllung eines biblischen Befehls diente: „Ihr sollt ihre Altäre zerstören, ihre Bilder zerbrechen und ihre Haine abhauen; … denn der Herr, dessen Name Eiferer ist, ist ein eifernder Gott“ (Exod. 34,13 f.). Zum frühesten christlichen Bildersturm gehörte die teilweise Zerstörung eines kilikischen Asklepios-Tempels und die Zerstörung von Aphrodite-Tempeln in Phönizien (ca. 326 n. Chr.). Konstantins Söhne Constans und Constantius II. traten in die Fußstapfen ihres Vaters. Im Jahr 341 erließ Constans ein Edikt, das Tieropfer verbot. Im Jahr 346 erließen Konstans und Constantius II. ein Gesetz, das die Schließung aller Tempel anordnete. Angestachelt wurden diese Kai-ser von dem christlichen Fanatiker Firmicus Maternus, der 346 in einer an beide Kaiser gerichteten Ermahnung die „Vernichtung des Götzendienstes und die Zerstö-rung der profanen Tempel“ forderte. Die Tatsache, dass Heiden weiterhin wichtige Posten in der kaiserlichen Verwaltung besetzten, machte es schwierig, die aktive Zer-störung von Tempeln, Statuen und Inschriften gesetzlich zu regeln, ohne einen gro-ßen Teil der Bevölkerung des Reiches zu verärgern. Dennoch drückten die Söhne Konstantins ein Auge zu, wenn es um private Akte des christlichen Vandalismus und der Schändung ging.

Nach dem Tod von Constantius II. wurde Julian im Jahr 361 zum Kaiser er-nannt. Nachdem er in unter dem Einfluss heidnischer Erzieher aufgewachsen war, entwickelte er einen tiefen Hass gegen den „galiläischen Wahnsinn“. Die Thronbe-steigung ermöglichte es ihm, seinen Übertritt zum Hellenismus zu verkünden, ohne Repressalien befürchten zu müssen. Julian machte sich daran, die von seinem Onkel erlassene heidenfeindliche Gesetzgebung rückgängig zu machen. Er öffnete die Tempel wieder, stellte ihre Finanzierung wieder her und gab konfiszierte Güter zu-rück; er renovierte Tempel, die von christlichen Vandalen beschädigt worden waren; er hob die Gesetze gegen das Opfern auf und verbot den Christen den Unterricht in den Klassikern. Julians Wiederbelebung heidnischer religiöser Praktiken brach 363 ab, als er im Kampf gegen die persischen Sassaniden fiel.

Sein Nachfolger Jovian widerrief die Edikte Julians und machte das Christen-tum wieder zur bevorzugten Religion im Reich. Die Kaiser, die auf Jovian folgten, waren zu sehr mit der Invasion der Barbaren beschäftigt, als dass sie sich um interne religiöse Streitigkeiten kümmerten; es war zweckmäßiger, einfach die Toleranz auf-rechtzuerhalten, die das Edikt von Mailand Heiden und Christen gleichermaßen auf-erlegt hatte. Mit Gratian traten die antipaganen Konflikte erneut in den Vordergrund. Im Jahr 382 verärgerte er die Heiden, indem er den Siegesaltar aus dem Senat ent-fernte. Im selben Jahr erließ Gratian ein Dekret, das alle Subventionen für die heid-nischen Kulte, einschließlich der Priesterschaften wie die der Vestalinnen, beendete. Er stieß die Heiden noch weiter vor den Kopf, indem er die Insignien des pontifex maximus ablehnte.

Im Jahr 389 begann Theodosius seinen umfassenden Kampf gegen die alte römische Staatsreligion, indem er die heidnischen Feiertage abschaffte. Den Dekre-ten des Kaisers zufolge war das Heidentum eine Form von „natürlichem Irrsinn und hartnäckiger Anmaßung“, die trotz der Schrecken des Gesetzes und der Androhung von Verbannung nur schwer auszurotten war. Im Jahr 391 folgte eine noch repressi-vere Gesetzgebung, die das Opferverbot wieder einführte, den Besuch heidnischer Heiligtümer und Tempel verbot, die kaiserlichen Subventionen für heidnische Kulte einstellte, die Vestalinnen auflöste und Apostasie unter Strafe stellte. Er weigerte sich, den Altar des Sieges im Senatshaus wieder aufzustellen und widersetzte sich damit den heidnischen Forderungen. Jeder, der bei der Durchführung von Tieropfern oder Haruspizien entdeckt wurde, sollte verhaftet und hingerichtet werden. Im selben Jahr wurde das Serapeum, ein riesiger Tempelkomplex, in dem die Große Bibliothek von Alexandria untergebracht war, von einer Gruppe christlicher Fanatiker zerstört. Dieser Akt des christlichen Vandalismus war ein schwerer psychologischer Schlag für das heidnische Establishment.

Die Heiden, unzufrieden mit der vom Kaiser geförderten Kulturrevolution, die die alten Traditionen Roms auszulöschen drohte, scharten sich um den Usurpator Eugenius. Er wurde 392 von dem fränkischen Kriegsherrn Arbogast zum Kaiser er-klärt. Als nomineller Christ hatte Eugenius Mitgefühl mit der Notlage der Heiden im Reich und hegte eine gewisse Sehnsucht nach dem vorchristlichen Rom. Er stellte die kaiserlichen Subventionen für die heidnischen Kulte wieder her und gab den Sie-gesaltar an den Senat zurück. Dies verärgerte Theodosius, den Kaiser im Osten. Im Jahr 394 drang Theodosius in den Westen ein und besiegte Eugenius in der Schlacht von Frigidus in Slowenien. Damit endete die letzte ernsthafte heidnische Herausfor-derung für die Einführung des Christentums als offizielle Religion des Reiches.

Apologeten des Christentums argumentieren, dass die kaiserliche Gesetzge-bung gegen das Heidentum mehr Rhetorik als Realität war; ihre Durchsetzung wäre in Ermangelung eines modernen Polizeistaatsapparats schwierig gewesen. Dieser Einwand wird durch archäologische und epigraphische Belege widerlegt. Erstens hat die stratigraphische Analyse der städtischen Tempel gezeigt, dass die kultischen Ak-tivitäten um das Jahr 400, nach der Verabschiedung der theodosianischen Dekrete, praktisch zum Erliegen gekommen waren. Zweitens gingen der Bau und die Reno-vierung von Tempeln unter den christlichen Kaisern deutlich zurück. In Afrika und der Kyrenaika sind Inschriften zum Bau und zur Renovierung von Tempeln unter der ersten Tetrarchie weitaus häufiger als unter der konstantinischen Dynastie, als die Heiden noch eine bedeutende Mehrheit der Reichsbürger stellten. Bis zum Ende des 4. Jahrhunderts hatte die autoritäre Gesetzgebung der christlichen Kaiser die Stärke und Vitalität der alten polytheistischen Kulte ernsthaft untergraben.

Die Kaiser beließen es nicht bei der Schließung heidnischer religiöser Stätten. Im Jahr 435 n. Chr. erließ der triumphierende Theodosius II. ein Edikt, das die Zer-störung aller heidnischen Heiligtümer und Tempel im gesamten Reich anordnete. Er verhängte sogar die Todesstrafe für christliche Magistrate, die das Edikt nicht durch-setzten. Das Gesetzbuch Justinians, das zwischen 529 und 534 erlassen wurde, sieht die Todesstrafe für die öffentliche Befolgung hellenischer Riten und Rituale vor; be-kannte Heiden sollten sich im christlichen Glauben unterweisen lassen oder die Be-schlagnahmung ihres Eigentums riskieren; ihre Kinder sollten von Staatsbeamten er-griffen und zwangsweise zum christlichen Glauben bekehrt werden.

Die kaiserlich angeordnete Schließung aller städtischen Tempel führte zu einer Privatisierung der polytheistischen Verehrung. Dies verschärfte den Niedergang der heidnischen religiösen Kulte aufgrund der Objektabhängigkeit der rituellen Praxis, die ohne Statuen, Prozessionen, Feste, üppige Bankette und monumentale Bauten nicht vollständig verwirklicht werden konnte. In den städtischen Gebieten war die kaiserliche Gesetzgebung eindeutig wirksam. Sie wurde von professionellen Christen und eifrigen Magistraten rücksichtslos durchgesetzt, die die zusätzliche Kraft der römischen Armee nutzten, um ihren Willen durchzusetzen, insbesondere wenn Pre-digt und öffentliches Beispiel versagten.

Heidnische Riten und Rituale wurden noch einige Zeit nach der Schließung der städtischen Kultstätten in ländlichen Heiligtümern und Tempeln gepflegt. Diese blieben sozusagen abseits der ausgetretenen Pfade und waren schwieriger zu schlie-ßen. Kirchenmänner wie der feurige Johannes Chrysostomus waren sich dieser Tat-sache bewusst und ermahnten die reiche Landbevölkerung des Ostens, die Heiden auf ihren Landgütern zu bekehren. Diejenigen, die heidnische Anbetung auf ihren Land-gütern zuließen, machten sich ebenso schuldig an der Verletzung der kaiserlichen Anti-Heiden-Gesetzgebung wie die Heiden selbst. Christliche Wanderprediger wie Martin von Tours schwärmten über das Land aus, um durch Einschüchterung, Beläs-tigung und Gewalt Seelen für Christus zu gewinnen. Schließlich sorgten die aggres-sive Evangelisation, die Privatisierung der heidnischen Religionsausübung und die soziale Marginalisierung für den Tod des Heidentums in den ländlichen Gebieten. Die Christianisierung des Reiches war um 600 n. Chr. abgeschlossen, wobei unklar ist, inwieweit Christus als eine weitere Gottheit betrachtet wurde, die neben den alten heidnischen Göttern verehrt wurde.

Das Christentum ist eine Form des magischen Denkens. Es lässt sich nicht durch rationale Überzeugungsarbeit in großem Umfang verbreiten. Niemand kann erklären, wie Christus von den Toten auferstanden ist, wie Gott als drei Personen in einer existiert oder wie eine Bibel, die eine geozentrische, flache Erdkosmologie lehrt, ein unfehlbarer Wegweiser zur universellen Wahrheit sein soll. Dies sind „Mysterien“. Das macht das Christentum zu einer so gefährlichen und zerstörerischen Sekte. Die Bekehrung ist eine emotionale Angelegenheit, es sei denn, sie geschieht aus Gewinnsucht oder unter Androhung von Gewalt. Niemand wird „überzeugt“, Christ zu werden. Entweder muss die Person leichtgläubig genug sein, um die Leh-ren des christlichen Glaubens ohne zu hinterfragen zu akzeptieren, oder sie muss mit dem Schwert gewaltsam bekehrt werden. Durch letzteres gelang es den Christen, ihr Evangelium über die Reichsgrenzen hinaus zu verbreiten und nominell bis zum 14. Jahrhundert ganz Europa zu bekehren.

Die Ausbreitung des Christentums kann nicht losgelöst von der Anwendung von Gewalt verstanden werden. Die Barbaren, die in das westliche Imperium ein-drangen, mussten zum Christentum konvertieren, sobald sie römisches Gebiet betra-ten. Die Bekehrung zu dieser Religion war eine Bedingung für ihre Migration und ihre Ansiedlung auf kaiserlichem Boden. Als Heiden hätten sie nicht an der römi-schen Gesellschaft teilnehmen dürfen. Christliche Missionen jenseits der kaiserlichen Grenzen konzentrierten sich in der Regel auf die Bekehrung barbarischer Herrscher und ihrer Höfe. Sobald der König die neue Religion angenommen hatte, zwang er seine Gefolgsleute, mit ihm zu konvertieren. Dieses Muster tauchte schon früh bei der Christianisierung Europas auf. Diese Könige wurden als „neue Konstantine“ be-zeichnet, weil sie das Christentum annahmen, oft nachdem sie Christus für den Sieg in einer Schlacht angerufen hatten, wie Konstantin während der Schlacht an der Mil-vischen Brücke im Jahr 312, und dann die Religion dem Adel und dem einfachen Volk aufzwangen. Zu den frühesten dieser neuen Konstantine gehörte Caedwalla, der König von Wessex aus dem 7. Jahrhundert. Er fiel auf der Insel Wight ein und rotte-te die meisten der dort lebenden Jüten aus. Caedwalla ersetzte sie durch christliche Westsachsen und zwang die Überlebenden mit dem Schwert, zum Christentum über-zutreten. Ein anderer war Edwin, der König von Northumbria aus dem 7. Jahrhun-dert, der eine Mischung aus Bestechung und Drohungen einsetzte, um den Adel und das einfache Volk zur neuen Religion zu bekehren.

Nach dem Zusammenbruch des Abendlandes blieb das Christentum bis zum Jahr 1000 auf das europäische Festland zwischen der Elbe im Norden und der Donau im Süden beschränkt. Von Habgier und Machtgier motivierte Barbaren waren die treibende Kraft hinter der erneuten territorialen Ausdehnung der mittelalterlichen Christenheit. Sie waren beeindruckt von dem Reichtum, der Opulenz und der Macht Konstantinopels und der fränkischen Herrschaftsgebiete und wollten diese für sich selbst. Für den heidnischen Kriegsherrn war das Christentum mit den Cargo-Kulten Melanesiens vergleichbar. Wenn sein barbarischer Hofstaat nur alle Insignien der christlichen Religion trüge, wäre er so reich wie der Kaiser in Konstantinopel!

In einer erhellenden Anekdote hat der mittelalterliche Chronist Notker der Stammler die Mentalität der zum Christentum konvertierten Barbaren treffend be-schrieben. Im 9. Jahrhundert strömten die Dänen an den fränkischen Hof von Lud-wig dem Frommen, um sich taufen zu lassen. Als Gegenleistung für die Bekehrung schenkte Ludwig jedem Mann einen Satz brandneuer Gewänder und Waffen. Als Ludwig einmal die Gegenstände ausgingen, die er den Täuflingen schenken wollte, ließ er ein paar Lumpen zu einer groben Tunika zusammennähen und schenkte sie einem alten Dänen, der schon zwanzig Mal getauft worden war. „Wenn ich mich nicht für meine Nacktheit schämte, gäbe ich dir sowohl die Kleider als auch deinen Christus zurück“, erwiderte der Däne wütend. Die „Reisschüssel“-Christen des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts machen es schwer, diese Geschichte als eine weitere mönchi-sche Fabel abzutun.

Der machtbesessene König Stephan von Ungarn zwang seine Untertanen, zum Christentum zu konvertieren. Er glaubte, dass die Christianisierung seines König-reichs es so mächtig und einflussreich wie Byzanz machen würde. Es wurden Geset-ze erlassen, die die Ausübung heidnischer Rituale verboten. Stephan befahl allen Magyaren, am Sonntag in die Kirche zu gehen und die Fastenzeit und die Fastentage einzuhalten. Die Nichteinhaltung dieser drakonischen Gesetzgebung wurde hart ge-ahndet. Der Verzehr von Fleisch während der Fastenzeit wurde mit Gefängnis be-straft, die Arbeit am Sonntag mit der Konfiszierung der eigenen Werkzeuge und Lasttiere. Die gesetzliche Strafe für das Murmeln während eines Gottesdienstes war das Scheren des Kopfes, begleitet von einer schweren Auspeitschung. Die „schwar-zen“ Magyaren, die sich der von Stephan erzwungenen Bekehrung Ungarns wider-setzten, wurden grausam unterdrückt. Viele wurden von Stephans christlichen Solda-ten, die über die Unnachgiebigkeit ihrer heidnischen Feinde verärgert waren, gefol-tert und anschließend geblendet. Diese Männer zogen den Tod der Schande und Ent-ehrung vor, die mit der Zwangstaufe in eine fremde semitische Religion und Kultur verbunden waren.

Die Christianisierung in Polen löste eine ähnliche Welle der Gewalt aus. Mies-zko I. christianisierte Polen gewaltsam, um seine Herrschaft über das Land zu stär-ken und eine Zwangsbekehrung durch die Ostfranken zu verhindern. Der Götzen-dienst wurde durch die Zerschlagung heidnischer Götzen und Heiligtümer, die Be-schlagnahme von Ländereien und die Enthauptung von Konvertierungsverweigerern unterdrückt. Obwohl aus der Regierungszeit Mieszkos nur sehr wenige christliche Gesetze überliefert sind, schrieb sein Nachfolger Boleslaw I. vor, einem Mann die Zähne auszuschlagen, wenn er sich weigerte, die Fastenzeit einzuhalten. Unzucht wurde bestraft, indem man den Hodensack eines Mannes an eine Brücke nagelte und ihn vor die Wahl zwischen Tod und Kastration stellte.

Die Brutalität dieser Methoden führte zu einer großen heidnischen Reaktion auf die Christianisierung Polens. Die Heiden schlugen zurück, indem sie christliche Priester töteten und Kirchen zerstörten. Mitte des 11. Jahrhunderts versank das Land im Chaos, die christliche Kirche in Polen wurde fast ausgelöscht und die Dynastie von Mieszko vorübergehend von der Macht vertrieben.

Die Sachsenkriege Karls des Großen, die von 772 bis 804 dauerten, waren das erste Mal in der Geschichte, dass das Christentum als Instrument der imperialisti-schen Eroberung eingesetzt wurde. Karl der Große leitete die formellen Feindselig-keiten ein, indem er heidnische Denkmäler in Sachsen zerstörte. Im Jahr 782 rächte Karl der Große prompt eine fränkische Niederlage gegen Sachsen, indem er 4.500 Sachsen in einer grausamen Vergeltungsaktion massakrierte. Das Sachsenkapitulat von 785 ordnete die Todesstrafe für jeden Sachsen an, der sich der Taufe widersetzte oder heidnische Bräuche praktizierte.

Herrscher bekehrten Heiden aus Gründen der persönlichen Selbstverherrli-chung gewaltsam zum Christentum. Michael III., Kaiser in Konstantinopel, zwang den bulgarischen Khan Boris 864 zur Annahme des östlichen orthodoxen Ritus, nachdem er in einer Schlacht besiegt worden war. Die erzwungene Christianisierung ermöglichte es Michael, seinen Einflussbereich auf dem Balkan auszuweiten. Bulga-rien wurde daraufhin von byzantinischen Geistlichen überschwemmt, die mit Hilfe von Boris’ Armee eine landesweite Kampagne zur Zerstörung aller heidnischen Heiligtümer starteten. Die Bojaren warfen dem Khan vor, Gesetze zu akzeptieren, die die Stabilität und Autonomie des Staates bedrohten. Im Jahr 866 lehnten sie sich gegen die Zwangschristianisierung des Landes durch den Khan auf, wurden aber mit großer Grausamkeit niedergeschlagen. Im letzten Jahrzehnt des neunten Jahrhunderts versuchte Boris’ ältester Sohn Wladimir, der Herrscher Bulgariens wurde, das Chris-tentum zu beseitigen und das Heidentum wiederherzustellen. In diesem Bestreben wurde er von den Bojaren unterstützt. Wladimir befahl die Ermordung christlicher Priester und die Zerstörung von Kirchen. Boris sah sich gezwungen, seine klösterli-che Klause zu verlassen und den Aufstand niederzuschlagen. Wladimir wurde abge-setzt, geblendet und in einen Kerker gesperrt – niemand hörte je wieder etwas von ihm.

Im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert wurden Kreuzzüge unternommen, um die einhei-mischen Völker Skandinaviens und des Baltikums zum Christentum zu bekehren. Es gab Kreuzzüge gegen die Wenden, Finnen, Livländer (Letten und Esten), Litauer und Pruzzen. Bernhard von Clairvaux, ein Mönchsreformer, forderte die kulturelle und physische Ausrottung der Nordeuropäer, die sich der Zwangsbekehrung zum Christentum widersetzten.

Was hat das Christentum für Europa getan?

Das Christentum ist eine gewalttätige, zerstörerische, mörderische Sekte. Es ist aus den folgenden Gründen gefährlich: 1.) Die Religion fördert das Überleben der Kranken, Schwachen und Dummen auf Kosten einer guten Rassenhygiene. Dies senkt den IQ der Bevölkerung und ihre Fähigkeit, zivilisatorische Leistungen zu er-bringen, drastisch, und 2.) der Kult setzt auf blinden Glauben statt auf rationale Überzeugung, was zu langen Perioden weit verbreiteten Chaos und Blutvergießens geführt hat, insbesondere während der Christianisierung Europas. Diese Gefahren wurden sogar von zeitgenössischen heidnischen Schriftstellern erkannt, die sofort die Bedrohung erkannten, die ein triumphierendes Christentum für das Überleben der westlichen Kultur darstellen würde.

Das Christentum hat die Europäer nie „zivilisiert“ oder „gebessert“. Im Ge-genteil, die Europäer waren gezwungen, eine neolithische Existenz zu ertragen, als die Christen auf dem Höhepunkt ihrer Macht und ihres Einflusses waren. Die Kirche schickte Männer mit geistigen Gaben in Klöster oder weihte sie zum Priestertum. Dadurch wurden sie daran gehindert, ihre Gene weiterzugeben, was zu einem erheb-lichen dysgenischen Effekt führte, der den kollektiven europäischen IQ senkte. Nur die heidnische Wissenschaft und die Vernunft des klassischen Altertums konnten die Europäer nach 500 Jahren völliger intellektueller Finsternis wieder bessern.

Die Kirche habe Europa erfolgreich gegen eine Invasion verteidigt, argumen-tieren einige Apologeten, aber nichts könnte weiter von der Wahrheit entfernt sein. Die Konfiszierung von Kircheneigentum durch Karl Martel zur Verteidigung Euro-pas gegen mohammedanische Eindringlinge stieß auf erheblichen kirchlichen Wider-stand. Wäre es der Kirche gelungen, die erforderlichen Mittel zurückzuhalten, wäre ganz Europa zu einer Provinz des Umayyaden-Kalifats geworden. Dennoch gelang es Martel nicht, die Sarazenen über die Pyrenäen zu verfolgen und sie aus ihrer an-dalusischen Festung zu vertreiben. Die Mohammedaner setzten ihre Besetzung der Iberischen Halbinsel 800 Jahre lang fort, bis sie Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts von Fer-dinand und Isabella endgültig vertrieben wurden. Der Südwesten Frankreichs und Italiens wurde von Zeit zu Zeit von mohammedanischen Eindringlingen überfallen und manchmal auch beherrscht. Das Emirat Sizilien bestand über zwei Jahrhunderte lang. Auch nach der normannischen Eroberung blieb eine bedeutende mohammeda-nische Präsenz auf der Insel bestehen. Mitte des 13. Jahrhunderts wurden die Mo-hammedaner endgültig von Sizilien vertrieben. Die Kreuzzüge zur Rückeroberung des Heiligen Landes von den Sarazenen (1095–1291), eine Reihe groß angelegter Militäroperationen unter der gemeinsamen Führung des Papsttums und des Feuda-ladels, verfehlten ihr Hauptziel. Im Jahr 1204 plünderten christliche Kreuzfahrer Konstantinopel in einer Orgie aus Vergewaltigung, Plünderung und Mord. Die Kreuzfahrer richteten so viel Schaden an, dass die Byzantiner ihren osmanischen Er-oberern 1453 keinen Widerstand mehr leisten konnten.

Das Christentum hat Europa nicht angemessen verteidigt. Die Kirche tat nur genug, um sich selbst als lebensfähige Institution zu erhalten. Dadurch schwächte die Kirche Europa und machte es reif für die Eroberung durch die Kalifate der Uma-yyaden und Osmanen.

Apologeten räumen zaghaft ein, dass das Christentum zwar den wissenschaft-lichen und technischen Fortschritt behindert, aber dennoch „Beiträge“ zu so unter-schiedlichen Bereichen wie Architektur und Philosophie geleistet habe. Bei näherer Betrachtung sind diese „Beiträge“ weder „christlich“ noch würdig, als „Beiträge“ be-zeichnet zu werden. Häufig werden die großen Kirchen des Mittelalters angeführt, die jedoch ihren Ursprung in der römischen Bauweise haben. Die Kuppel, der Bogen und das Gewölbe, die typischen Merkmale des mittelalterlichen romanischen Bau-stils, sind allesamt der römischen Kaiserarchitektur aus vorchristlicher Zeit entlehnt. Das architektonische Grundschema der meisten mittelalterlichen Kirchen ist die rö-mische Basilika, ein öffentliches Gebäude, das offiziellen Zwecken vorbehalten war. Selbst die Gotik, die die Romanik ablöste, verwendete noch architektonische Merk-male römischen Ursprungs. Das für die gotische Architektur typische Kreuzrippen-gewölbe wurde ursprünglich im römischen Kolosseum des Vespasian und von Hadri-an beim Bau seiner tiburtinischen Villa verwendet.

Während der christliche Religiöse die Romanik als „Errungenschaft“ aner-kennt, ignoriert er bequemerweise das fast vollständige Verschwinden der römischen Baumethoden aus Westeuropa für fast 300 Jahre. Dies war eine direkte Folge der ak-tiven Unterdrückung westlicher wissenschaftlicher und technischer Erkenntnisse durch die Kirche. Von der Fertigstellung von Theoderichs Mausoleum in Ravenna bis zur Weihe des Aachener Doms im Jahr 805 wurde in Westeuropa nichts mehr von monumentaler Bedeutung gebaut. In der Zwischenzeit kehrten die Europäer wie ihre neolithischen Vorfahren zur Verwendung von nicht haltbaren Baumaterialien zurück.

Apologeten des Christentums führen Thomas von Aquin und die Scholastik als Höhepunkte nicht nur der mittelalterlichen, sondern auch der europäischen intellek-tuellen Entwicklung an, obwohl der Aquinate den europäischen wissenschaftlichen und technischen Fortschritt um Hunderte von Jahren zurückgeworfen hat. Die Scho-lastik wurde in der Renaissance zum Gegenstand von Spott und Hohn. Religionswis-senschaftler verweisen auf den christlichen „Beitrag“ der Universität und vergessen dabei, dass es bereits in der Antike zahlreiche Einrichtungen der höheren Bildung gab, die sogar florierten. Die ersten Universitäten lehrten Scholastik und waren so-mit die Frontlinie im christlichen Kampf gegen die heidnischen Werte der intellektu-ellen Neugier, der Liebe zum Fortschritt um seiner selbst willen und der empirischen Rationalität.

Nach christlich-religiöser Auffassung sind Wissenschaft und Technik christli-chen Ursprungs, weil die Männer, die während der wissenschaftlichen Revolution die Entdeckungen und Erfindungen machten, nominelle Christen waren, wie Galileo und Newton. Dieses Argument ist genauso absurd wie die Behauptung, dass die griechi-sche Erfindung von Logik, Rhetorik und Mathematik das Ergebnis griechischer heidnischer theologischer Überzeugungen war, weil Aristoteles und andere antike Wissenschaftler und Philosophen Heiden waren. Nein, diese Männer waren „Chris-ten“, weil das öffentliche Bekenntnis zum Atheismus in einer Zeit gefährlich war, in der selbst die harmlosesten theologischen Spekulationen den Ruf schädigen und Kar-rieren zerstören konnten. Es ist eine glühende Anerkennung für den Mut und die Ehrlichkeit dieser Männer, dass sie in der Lage waren, das Vertrauen des Christen-tums in den blinden Glauben aufzugeben, oft im Angesicht öffentlicher Kritik, und bewusst die heidnischen erkenntnistheoretischen Werte wieder aufzunehmen, die 2000 Jahre vor der wissenschaftlichen Revolution das „griechische Wunder“ hervor-gebracht hatten.

Christliche Religiöse behaupten, dass das Neue Testament, eine Sammlung kindlicher Kritzeleien, die von halbwissenden Barbaren verfasst wurden, einen gro-ßen Beitrag zur westlichen Zivilisation darstellt. Wie seit Generationen, sogar von anderen christlichen Religiösen, immer wieder betont wird, ist das Werk berüchtigt für seine schlechte Grammatik und seinen ungeschliffenen literarischen Stil. Ein großer Teil wurde von Juden verfasst, die nicht einmal die griechische Sprache be-herrschten. Insgesamt ist das Neue Testament eine minderwertige Produktion im Vergleich zu den gewöhnlichsten Schriftstellern der attischen Prosa. Selbst der heili-ge Hieronymus, der Übersetzer der Vulgata, äußerte sich verächtlich über den plum-pen, wenig anspruchsvollen literarischen Stil der Bibel. Er bevorzugte stattdessen das elegante Latein Ciceros.

Was hat das Christentum zu Europa beigetragen? Die Antwort lautet: nichts! Keine Kunst, Kultur, architektonische Denkmäler, Wissenschaft oder Technologie. Das Christentum war eine massive Verschwendung des europäischen intellektuellen und physischen Potenzials. Außerdem hat das Christentum Europa fast zerstört.

Die Kirche verwarf über 99 % der antiken Literatur, einschließlich der Werke der Wissenschaft, Mathematik, Philosophie, Technik und Architektur. Dies war die größte Kampagne der literarischen Zensur und Unterdrückung in der Geschichte, ein Akt des kulturellen und physischen Völkermords, der das mittelalterliche Europa fast von den großen Errungenschaften der klassischen Antike abschnitt. Es handelte sich um einen kulturellen Völkermord, weil die Kirche fast eine ganze Zivilisation und Kultur auslöschte; es handelte sich um einen physischen Völkermord, weil die ab-sichtliche Ausrottung weltlichen Wissens durch die Kirche Millionen von Menschen-leben in Gefahr brachte und sie unnötigerweise den Verwüstungen von Krankheit, Krieg, Hunger und Armut aussetzte. Die christliche Kirche ist alles andere als gutar-tig, sondern eine machtbesessene religiöse Mafia. Sie trägt die alleinige Verantwor-tung für die größten Verbrechen, die in der Geschichte an den Europäern begangen wurden. Wie lange wird die christliche Kirche der Bestrafung für dieses kriminelle Fehlverhalten entgehen? Keine andere Religion hat Europa so viel Leid und so viel Schaden zugefügt wie diese geistige Syphilis, die als Christentum bekannt ist.

Das Christentum: die Großmutter des Bolschewismus?

1933 schrieb der deutsche Historiker Oswald Spengler: „Alle kommunisti-schen Systeme im Westen sind in Wirklichkeit aus dem christlichen theologischen Denken abgeleitet… Das Christentum ist die Großmutter des Bolschewismus.“ Allein das macht das Christentum zu einer der zerstörerischsten Kräfte der Weltgeschichte, einer Kraft, die so radioaktiv ist, dass sie alles in ihrer unmittelbaren Umgebung zer-stört. Aber wie ist das überhaupt möglich?

Die Gleichheit ist ein so grundlegender Aspekt des kirchlichen Kerygmas, dass das gesamte ideologische Gefüge der christlichen Orthodoxie wie ein Kartenhaus zusammenbrechen würde, wenn man es beseitigen würde. Die „Katholizität“ der Kirche bedeutet, dass die Mitgliedschaft im Leib Christi allen Menschen offensteht, unabhängig von ethnisch-sprachlichen oder sozioökonomischen Unterschieden. Da das Heil für alle gleichermaßen zugänglich ist, bedeutet dies, dass alle Menschen die gleiche angeborene Fähigkeit besitzen, es zu erlangen. Es gibt auch eine universelle Gleichheit in der sündigen Verderbtheit sowie im Besitz der unverdienten göttlichen Gnade. Das Gebot Jesu, den Nächsten zu lieben wie sich selbst, ist lediglich die Anwendung universalistischer und egalitärer Prinzipien auf das menschliche Sozialleben. Im Neuen Testament werden die Gläubigen aufgefor-dert, einander zu dienen, mit dem Ziel, soziale Gleichheit in einem kirchlichen Rah-men zu erreichen.

Die Aneignung des platonischen Idealismus durch die vornizäischen Theolo-gen fügte den egalitären Aussagen des Neuen Testaments eine metaphysische Dimen-sion hinzu. Als Gott den Menschen schuf, hauchte er ihm durch die Nasenlöcher den Lebensatem ein. Dieser „Atem“, psyche oder anima, übersetzt „See-le“, diente als Lebensprinzip des belebten Körpers. Die Gleichheit der Seelen vor Gott ist gegeben, weil alle die gleiche imago dei oder das gleiche Ebenbild Gottes tragen. Im Garten Eden lebte der Mensch in einem Zustand natürlicher Gleichheit. Der heilige Augustinus schreibt, dass vor dem Sündenfall niemand Herr-schaft über einen anderen ausübte, sondern dass alle gleichberechtigt und ohne Un-terschiede über die niedere Schöpfung herrschten. Die natürliche Gleichheit, die es in dieser mythischen Vorgeschichte einmal gab, ging durch die Sünde verloren, die die menschliche Natur verdarb. Dies brachte die Sklaverei und andere Ungleichhei-ten in die Welt. Die Kirche glaubte, dass das Reich Gottes am Ende der Zeit die Verhältnisse Edens wiederherstellen würde.

Für die vornizäische Kirche war der Glaube an die geistige Gleichheit keine verknöcherte Formel, die wie das Apostolische Glaubensbekenntnis auswendig rezi-tiert werden musste, sondern eine allgegenwärtige Realität mit realen, „vorwegge-nommenen“ Konsequenzen. Evangeliumsgeschichten, die Elemente des primitiven Kommunismus enthielten, nahm die Kirche wohlwollend auf und erklärte sie als ka-nonisch. In Lukas 3 ermahnt Johannes der Täufer, ein Mitglied der kommunistischen

Essener, seine Anhänger, ihre Kleidung und Nahrung mit den Bedürftigen zu teilen. Die kommunistischen Äußerungen des Johannes lassen den deutlicheren primitiven Kommunismus Jesu vorausahnen.

In Lukas 4 beginnt Jesus seinen Dienst, indem er ein annehmbares „Jahr der Gunst des Herrn“ einläutet. Dies ist eine direkte Anspielung auf das hebräische Ju-beljahr, das alle fünfzig Jahre nach Abschluss von sieben Sabbatzyklen stattfand. Die Verkündigung des Jubeljahres bedeutete die Freilassung der Sklaven, den Erlass der Schulden, die Neuverteilung des Eigentums und das gemeinsame Eigentum an den natürlichen Erzeugnissen des Landes. Nach Levitikus gehörte das Land niemandem außer JHWH; nur sein Nießbrauch konnte erworben werden. Es handelte sich nicht um ein buchstäbliches Jubeljahr, das Jesus einleitete. Die Passagen, die bei Lukas zi-tiert werden, stammen aus Jesaja und nicht aus Levitikus, das die eigentliche hebräi-sche Gesetzgebung enthält. Die mit dem Jubeljahr verbundene Symbolik wird ver-wendet, um die eschatologischen Merkmale des neuen Zeitalters zu beschreiben, das durch den kommenden Messias eingeleitet wird. Seine Rückkehr symbolisiert die vollständige Umkehrung der alten Ordnung. Das neue Zeitalter wird durch die ethi-sche Umgestaltung der Gläubigen kommunistische soziale Beziehungen hervorbrin-gen. Vom biblisch-hermeneutischen Standpunkt aus gesehen ist das Jubiläum der To-ra ein Vorgeschmack auf das größere Jubiläum, das nun im Wirken Jesu verwirk-licht wird.

Die wirtschaftlichen Lehren Jesu gehen weit über das levitische gemeinschaft-liche Teilen hinaus. Sie erfordern eine groß angelegte Umstrukturierung der Gesell-schaft nach egalitären und kommunistischen Grundsätzen. In Lukas 6 befiehlt Jesus seinen Zuhörern, allen zu geben, die sie anflehen, ohne Unterschied, ob sie Freund oder Feind sind. Seine Verurteilung gewaltsamer Vergeltung steht in engem Zusam-menhang mit dieser Ethik des allgemeinen Teilens; die von Jesus angestrebte kom-munistische Gesellschaftsordnung kann in einer Atmosphäre der Gewalt und des Misstrauens nicht gedeihen. Das vom Messias eingeleitete eschatologische Zeitalter ist eines, in dem das Verleihen ohne Erwartung einer finanziellen Gegenleistung zu einer neuen moralischen Verpflichtung geworden ist, die man erfüllen muss, wenn man einen Schatz im Himmel erlangen will.

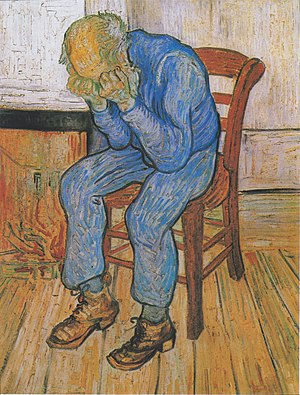

When I was a teenager, my mother’s slander against me was horrendous (she had lost her mind). But it was my father’s folie à deux that destroyed me (see details in Letter to mom Medusa, a book whose English translation I advertise on the sidebar). My father was not a simple victim of ill advice, but an active agent in believing everything to his Medusa wife. Since he could have chosen not to let himself be stung by the snakes of her wife’s scalp, but let himself be poisoned for decades, I cannot forgive him, or say that the ‘poor’ Anglo-Americans were victims of ill advice by the Jewish slander against the Germans.

When I was a teenager, my mother’s slander against me was horrendous (she had lost her mind). But it was my father’s folie à deux that destroyed me (see details in Letter to mom Medusa, a book whose English translation I advertise on the sidebar). My father was not a simple victim of ill advice, but an active agent in believing everything to his Medusa wife. Since he could have chosen not to let himself be stung by the snakes of her wife’s scalp, but let himself be poisoned for decades, I cannot forgive him, or say that the ‘poor’ Anglo-Americans were victims of ill advice by the Jewish slander against the Germans.