Early in his career Nietzsche had planned to write a work entitled Passio nuovo, or the Passion for Sincerity. The book was never written; but, what was perhaps better, it was lived in Nietzsche’s own person. For throughout the philosopher’s years of growth and change, a fanatical passion for truthfulness remained as the primitive and fecundating element of all he undertook. For such reasons the sincerity of a man like Nietzsche has nothing akin to the trite honesty of a carefully trained gentleman. His love of truth is a flame, a demon of veracity, a demon of lucidity, is a hunting beast ever on the prow.

Such an attitude of mind accounts for Nietzsche’s detestation of those who, through slackness or cowardice in the realm of thought, neglect the sacred task of straightforwardness; hence his anger against Kant, because that philosopher, while turning his blind eye to the postern, allowed the concept of the godhead to slip back into his system. Lacking sincerity, we cannot hope to attain to knowledge; lacking resoluteness, we cannot hope to be sincere. “I become blind from the moment when I cease to be sincere. If I wish to know, I must be sincere, that is to say, I must be hard, severe, narrow-minded, cruel, inexorable.”

Like all fanatics, he sacrificed even those he loved (as in the case of Richard Wagner, whose friendship had been for Nietzsche one of the most hallowed). He allowed himself to become penurious, solitary, detested, an anchorite and miserable, solely with a view to remaining true to himself, in order to fulfill his mission as apostle of sincerity. This passion for sincerity became, as time elapsed, a monomania in which the good things of life were absorbed.

Nietzsche practised philosophy as a fine art; and, as an artist, he was not concerned with results, with definitive things, with cold calculations. What he sought was style, “morality in the grand style,” and as an artist he experienced and enjoyed the pleasures of unexpected inspiration. It may be a mistake to apply the word philosopher to such a man, for a philosopher is “the lover of wisdom.”

Passion can never be wise. More appropriate to him would be the appellation, “philaleth,” a passionate lover of Aletheia, of truth, of the virginal and cruelly seductive goddess who never tires of luring her admirers into an unending chase, and finally remains inaccessible behind her tattered veils. Nietzsche, as the slave and servant of the daimon, sought excitement and movement pushed to an extreme. Such a fight for the inaccessible has a heroic quality, and heroism almost invariably ends in the destruction of the hero.

Excessive claims for truth come into conflict with mundane affairs, for truth is implacable and dangerous. In the end, so fanatical an urge for truth kills itself. Life is, fundamentally, a perpetual compromise. How well Goethe, in whose character the essence of nature was so exquisitely poised, recognized this fact and applied it to all his understandings! If nature is to keep its balance, its needs, just as mankind needs, to take up an average position, to yield when necessary, to concede points, to form pacts.

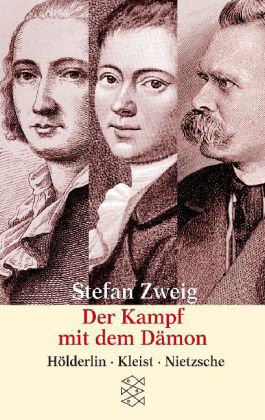

He who presumes the right of non-participation, who refuses to compromise with the world around him, who breaks off relationships and conventions which have been slowly built up in the course of many centuries, becomes unnatural and anthropomorphic in his demands, and enters into opposition against society and against nature. The more such an individual “aspires to attain absolute integrity,” the more hostile are the forces of his epoch. If, like Hölderlin, he persists in an endeavor to give a purely poetical twist to an essentially prosaic existence, or if, following Nietzsche’s example, he aims at penetrating into the infinitude of terrestrial vicissitudes, in either case such an unwise desire constitutes a revolt against the customs and rules of society, separates the presumptuous being from his fellow-mortals, and condemns him to perpetual warfare which, splendid though it may be, is foredoomed to failure.

What Nietzsche named the “tragic mentality,” the resolve to probe any and every feeling to the uttermost, transcends spirit and invades the realm of fate, thereby creating tragedy. He who wishes to impose one single law upon life, who hopes, amid the chaos of passions, to make one passion (his own peculiar passion) supreme, becomes a solitary and in isolation suffers annihilation.

Nietzsche recognized the peril. But, as a hero in the realm of thought, he loved life precisely because it was dangerous and annihilated his personal existence. “Build your cities on the flanks of Vesuvius!” he exclaimed, addressing the philosophers in the endeavour to goad them into a more lofty consciousness of destiny; for the only measure of grandeur is, according to Nietzsche, “the degree of danger at which a man lives in relation to himself.” He only who takes his all upon the hazard has the possibility of winning the infinite; he only who risks his life is capable of endowing his earthly span with everlasting value. “Fiat veritas, pereat vita”; what does it matter if life be sacrificed so long as truth is realized? Passion is greater than existence, the meaning of life is of more worth than life itself.

The last few steps he took into this sphere were the most unforgettable and the most impressive in the gamut of his destiny. Never before had his mind been more lucid, his soul more impassioned, his words more tipped with joyful music, than when he hurled himself in full consciousness and wholeheartedly from the altitudes of life into the abyss of annihilation.

3 replies on “Passion for sincerity”

I read this book in Houston in 1996, six years before I discovered the work of Alice Miller on Nietzsche. In 1996 Zweig’s study deeply impressed me. Today that I typed these excerpts directly from Zweig’s book I see my mind very changed.

However, unless questioned this is no place to write down why I believe that here Zweig is wrong with his philosophy of compromising with the current zeitgeist, although those racialists who feel alienated in our culture might figure out in which ways Zweig’s philosophy is questionable (though my approach is more focused on the implications of Z’s philosophy on my life than on racialism or Nietzsche’s own life).

Off topic:

If I may give you a suggestion, I think it would be interesting if TWDH featured some commentary about the news of the day. I mean, there are plenty of righ wing bloggers who comment on the daily news (Steve Sailer, for example), but none of them is a White nationalist like you, Chechar. It would be great to read political commentary from a person with your views.

Be my guest. But I cannot do it by myself because I’m extremely alergic to the MSM and the press 🙂