In my previous post on Tom Goodrich, I said: ‘Only those who are knocked off the tower by their parents or guardians and become disabled, but are survivors, are able to cross the Wall in search of the raven’, tacitly referring to the metaphor of the featured post in this blog. I want to delve a little deeper into the subject. In a 2015 interview, Goodrich confessed early on:

Born in Kansas as Michael Thomas Schoenlein, I was adopted at age five. I spent my first years on my grandma’s farm in Missouri, then moved to Kansas. My biological dad was a professional musician, alcoholic and drug addict. About the age of 8-11, I was raped and sodomized on a daily basis. Other than that, I led a fairly normal childhood. After the military, I graduated from Washburn University in Kansas with a degree in history.

As every old visitor knows, I too was abused as a minor, but an even more serious abuse than sexual abuse: one of those that murder the soul (cf. Letter to mom Medusa; the next book, one I will soon begin translating into English, is entitled How to Murder Your Child’s Soul).

The vast majority of visitors to The West’s Darkest Hour imagine that these are parallel themes, Aryan preservation and the mistreatment of children (or adolescents, as was my case). But everything to do with the humanities, and indeed animals, is interrelated. For example, it will be recalled that this year I wrote some articles about Marco, a friend of the chess club whom I met half a century ago but recently visited and found him in a very clearly psychotic condition (I refer to what I wrote from the end of February to the beginning of March in six posts: #1, #2, #3, #4, #5 and #6). But the psychosis of this poor devil, who is not even able to make an appointment because of his malignant narcissism (cf. instalment #3), can be observed in millions of normal people.

Yesterday, for example, I watched a recent interview between the American John Mearsheimer and the Russian intellectual Alexander Dugin. From this point on in the conversation both Mearsheimer and Dugin spoke, without mentioning the term, of the malignant narcissism that currently afflicts the entire American elites, as incapable of putting themselves in the shoes of the Other as Marco. Dugin even mentioned a rather curious personal anecdote, that there are American politicians who are under the impression that chess is… a one-person game (!), presumably the American who plays solo ‘chess’.

In my soliloquies, I have said it to myself countless times: sometimes normal people are as psychotic as Marco, but the difference is that the latter lives on government charity and his first cousin. The narcissist in a psychotic state can no longer move in the real world on his own; the elites like those mentioned by Mearsheimer and Dugin can, which makes them infinitely more dangerous than the ordinary madman.

Marco had a mother who murdered his soul, though the disorder came very late in his life. Goodrich also had someone as abusive as Marco’s mother, but unlike him Goodrich not only survived psychologically but ennobled his soul to the extent of becoming an overman (the crow metaphor I use so much).

So, taking into account the recent conversation between Mearsheimer and Dugin, I could say that the two themes that have moved me to write are related: the psychic ravages of parental abuse, and deciphering why the white race is committing suicide: which includes the narcissistic American elites. In fact, I dare say that only people who, like Tom, were able to develop an emergent spin on their personal tragedy, have been able to see the historical past as it happened: and precisely for the reasons Tom mentioned in my post yesterday, to humbly listen to the voice of the vanquished.

Only a person who was internally broken, but who unlike millions of madmen didn’t succumb to psychosis (‘What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger!’) was able to understand what the German people suffered in WW2, even up to 1947 when the Allies were still perpetrating a Holocaust of defenceless Germans.

That man was Tom.

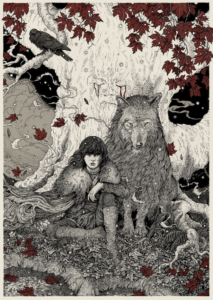

As one of the very fans who grasped George R.R. Martin’s philosophy said, passages I have quoted on this site:

Much like the audience, the seven kingdoms don’t understand what Bran has become, or how he helped save the world. Yet, when Bran returns, the kingdom is broken just like him; and all the things that once made him useless to the militaristic culture of Westeros, now make him the ideal Fisher King: an incorruptible figurehead to help usher the new system. And thus Bran the Broken is immortalized as the story around which the kingdoms of Westeros can unite.

That passage appears in ‘The power of stories’, a video linked by me recently. Here is another passage from another fan:

GRRM’s answer to the question ‘How can mortal men be perfect kings?’ is evident in Bran’s narrative: Only by becoming something not completely human at all, to have godly and immortal things, such as the Weirwood, fused into your being, and hence to become more or less than completely human, depending on your perspective. This is the only type of monarchy GRRM gives legitimacy, the kind where the king suffers on his journey and is almost dehumanized for the sake of his people.

Tom Goodrich’s tragic journey into inner space certainly taught us to know outer space better than conventional WW2 historians, who, being unable to touch the Weirwood with the palm of their hands, never saw the past as it really happened.

4 replies on “Goodrich”

I can empathise directly (a little) with Tom, and with yourself. I was reading my latest book to my girlfriend tonight as she has been up until now unaware of the details of my childhood. Not the entire thing, just selected passages, in a hurry, knowing I haven’t got that much time. I found my voice wavered over the earliest bullying/molestation at 5 and 6, but, over the 11-13 segments, I wasn’t actually too moved, only really developing a more mournful, hesitant tone when approaching home life again, and my relationship with my father and mother (the latter’s cowardly treachery and the former’s caustic belligerence). What you say about the murder of souls being even worse than sexual abuse seems on point (not that I wish to diminish sexual abuse, which is in itself devastating, and terrifying at times, if more visceral and relatively short-term as opposed to psychologically grinding, soul-severing, and life-long).

I flicked through to the latter pages, and reminisced over the friends and best friends I made in the childhood psychiatric unit I was placed in, remembering at least six lives (there are probably more – I was a very bad alcoholic and my memories of these years are marred by a now-generalized grief also) who killed themselves in horrible ways, and one who became a heroin addict; no one was treated by their ‘treatment’, and hardly anyone left there unscathed. It’s a shame, as, reading your words, I wonder what they could have gone onto had they not done that, what they could have realized and developed into. All had been abused as children, mostly by their parents.

I’m glad Tom was not destroyed by his journey, and that he went on to craft such vital historical contributions, an exemplary act of harrowing empathy rare to this world, and a respectful gift to the fallen sons and daughters of Germany. I’m sorry to hear he’s dead now.

I recommend his books to anyone I can, and have lent them out numerous times now.

Hello Ben,

I didn’t know that you were bullied and molested at age five or six. The earlier the abuse happened, the more severe the symptoms would be (I assume Marco was abused by his mother when he was a mere toddler).

Thanks for sharing…

That’s ok. Thanks for letting me. It’s hard to express my ‘case history’ as there are a lot of different little (and not so little) unrelated events. Basically there was some weird external abuse when I was 6 which I’ve tried to go over in my book, but don’t reference much, as I don’t understand it. It wasn’t my parents. My Dad was bullying me in my toddler years right up to late adolescence (and adulthood for that matter), getting increasingly worse towards me as I started to get ill, and then right there in the middle at 11-13 there was that Pakistani bully-abuser a year older than me with all his sexual deviancy. So I never know which bit really to get into first. A therapist would have a field day (if therapists legitimately existed in this country anymore who were willing to counsel actively on childhood trauma, which they don’t). My parents don’t know most of the details (I tentatively tested the waters repeatedly and found no empathy), and neither does anyone, which is why I hope my new book fills them in.

As I say, the second part will deal with the physical abuse in late adolescence; my Dad breaking my nose, that sort of thing, and all the more grisly symptoms and addictions. It’s definitely my relationship with my father that’s hurt me more than any of the rest, perhaps surprisingly, much as the stuff early on does bring me to dissociating tears admittedly (although since writing it down I can dwell on it for longer bursts).

Just like in my case: my father was the main perp (something that is not clearly evident until my third book, Lágrimas)…