Worse still than the old European imperialism of western powers, according to Hitler, was the Jewish aspiration to world domination, of which the Germans were the principal victims. Drawing on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, he claimed to see a grand plan to control the world. The ultimate aim of policy towards Germany and other independent states, Hitler stated at the beginning 1921, was the creation of a ‘Jewish world state’. He came back to this theme repeatedly over the next two years, when he spoke of the ‘Jewish-imperialist plans for world domination’, the ‘Jewish world dictatorship’ and the ‘final aim [of the Jews]: world domination [and] the destruction of the national states’. In his notes for one speech, Hitler made the connections absolutely clear in point form: ‘World domination with a Jewish capital—Zion—that means world enslavement: world stock exchange—world press—world culture. World language. All for slaves under one master.’ In this way, Hitler closed the circle of western imperialist, Jewish and capitalist enemies of the Reich…

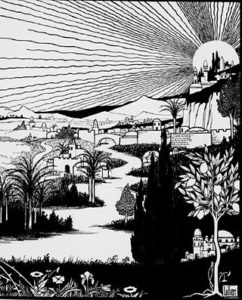

Left, Zion (1903), Ephraim Moses Lilien. ‘Zion’ (Hebrew: צִיּוֹן Ṣīyyōn, Septuagint, Σιών, is a placename in the Hebrew Bible, often used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole. —Ed.

Left, Zion (1903), Ephraim Moses Lilien. ‘Zion’ (Hebrew: צִיּוֹן Ṣīyyōn, Septuagint, Σιών, is a placename in the Hebrew Bible, often used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Israel as a whole. —Ed.

It is in this context that Hitler’s evolving attitude to communism and the Soviet Union should be seen. At times, he suggested that Bolshevism and international capitalism were working together. He spoke of the way in which Jewish capitalism allegedly used Chinese ‘cultural guardians’ in Moscow, and black ‘hangmen’s assistants’ on the Rhine, while the Soviets in Genoa ‘walked arm in arm with big bankers’. The Jews, Hitler claimed, ‘had their apostles in both camps’ and thus agents on both the ‘right’ and the ‘left’. From time to time, Hitler claimed that communism was the main threat. It is also true that after the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War, the threat of international communism loomed larger in his mind than it had in 1919. Hitler now called for ‘the overcoming and extermination of the Marxist worldview’. ‘Developments in Russia must be watched closely,’ he warned, because once the communists had ‘consolidated their power’ they would ‘probably turn it against us’…

Despite all this, Hitler still did not regard capitalism and communism simply as two equal sides of the same Jewish coin… More generally, his rhetoric and attention were still overwhelmingly directed towards the threat posed by the western powers and international finance capitalism.

For this reason, Hitler was bitterly opposed to any form of internationalism, not just because he despised it in principle, but because he considered it humbug. In part, this hostility was directed towards the German left, whose blind faith in universal principles, Hitler argued, had left Germany defenceless during the world war and its aftermath. For this reason, he argued, ‘[we should] free ourselves of the illusion of the [Socialist] International and [the idea of ] the Fraternity of Peoples’. Hitler’s main objection to internationalism, however, was that it simply served the interests of the western imperial powers.

Where was international law, he asked, when Louis XIV had plundered Germany in the late seventeenth century, when the British had bombarded neutral Copenhagen in 1807 and starved and oppressed the Irish, or when the Americans had displaced the native Indians. It had not escaped Hitler’s attention that ‘in the home of the inventor of the League of Nations [Wilson’s America] one rejects the League as a utopia, a madness’. There was not even a racial solidarity among whites, Hitler lamented, because France had sent ‘comrades from Africa in solidarity to enserf and muzzle the population on the Rhine’. For this reason, Hitler rejected the whole notion of international governance, claiming that ‘The League of Nations is only a holding company of the Entente which wants to secure its ill-gotten gains.’