– For the context of these translations click here –

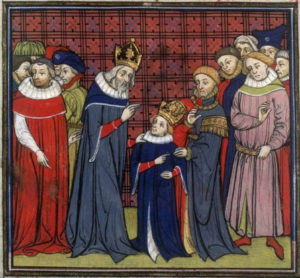

Charlemagne crowns Louis the Pious.

Louis I the Pious (814-840)

‘Ludwig’s empire was in fact to be an empire of peace… This, however, did not exclude wars against the pagans, but demanded them precisely, since they were regarded as allies of Satan.’ —Heinrich Fichtenau

Charlemagne, the saint, was not only active on the battlefields. As far as we know, he also had nineteen children, eight sons and eleven daughters, and of course with nine different wives (still an almost modest figure compared to the 61 children of Bishop Henry of Lüttich, that tireless worker in the vineyard of the Lord, or Pope Gregory X of the 13th century, who had ‘14 children in 22 months’).

But despite the Carolingian blessing of the sons, there was no problem in the matter of succession. In case of death, Charlemagne divided the empire among his three sons through the so-called Divisio regnorum. In addition, each was to assume the Defensio Sancti Petri, the protection of the Roman Church.

But quite unexpectedly the father saw the two eldest sons go to their graves: in 810 Pippin and the following year Charles, to whom the imperial crown had long been assigned as the main heir. All this affected the ruler to such an extent that he even considered becoming a monk. Of his ‘legitimate’ sons, only the youngest remained, and, as he was well aware, the one least suited to the throne: Louis, born in 778 in Chasseneuil near Poitiers. He would be enthroned emperor at the age of thirty-six, only to be deposed and enthroned again, losing the throne once more and regaining it later.

In any case, Louis the Pious had what it takes: even as a child ‘he had learned to fear and love God always’, as one of his contemporary biographers reports around 837. Charles exhorted his son and successor to love and fear the Almighty especially, to keep his commandments in all things, to rule his churches, to honour priests as fathers and to love the people as his children. He was to force proud and wicked men to enter the way of salvation, help the monasteries and procure God-fearing servants.

From that coronation onwards Charles, who was already quite decrepit and limping on one foot, did nothing—if we are to believe Bishop Thegan—but pray, give alms and ‘improve’ or ‘correct magnificently’ (optime correxerat), as Thegan himself says, the four gospels, the infallible word of God, before he died on 28 January 814. He left his son a gigantic empire, almost entirely the fruit of the plundering that he and his illustrious predecessors and ancestors had carried out, and consisting of four strong units: France, the centre of the state with the royal courts and the great abbeys; Germania, Aquitaine and Italy.

Killing and praying

Two fields that had long defined every Christian ruler, and would continue to define them decisively for many centuries, also marked the life of the young Ludwig: war and the Church. All Christian nobles had to learn the profession of war from an early age. As a rule, they had to be trained in equestrian combat even before puberty, and at the age of fourteen or fifteen, and sometimes even earlier they had to be able to handle weapons. And naturally, ‘the nobles were burning with the desire to go into battle’ (Riché).

Louis, too, who had a vigorous body and strong arms, and who in the art of riding, drawing the bow and throwing the spear ‘had no equal’, but who, according to the results of research, was a peaceful man, accompanied his father in his desire to annihilate the Avars at least as far as the Viennese forest. Shortly afterwards, in 793, again on his father’s orders, he supported his brother Pippin in a punitive campaign in southern Italy.

And yet Ludwig was a particularly good Christian, even better than his saintly father. On Charles’s orders, the pious and peaceful son also broke into Spain. He subdued and destroyed Lerida. ‘From there,’ writes the Astronomus, ‘and after having devastated and burned the other cities, he advanced as far as Huesca. The territory of the city, abundant in fields of fruit trees, was razed, devastated and burnt by the troops and everything that was found outside the city was annihilated by the devastating action of the fire.’

As was almost always the case at the time, only winter prevented the young Louis from pursuing the actions typical of Christian culture. For the rest, the Catholic hero not only set fire to cities, but sometimes also burned men, but only ‘according to the law of retaliation’ (Anonymi vita Hludovici). All very biblical: an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. And, according to the same source, as soon as ‘this was done, the king and his advisors felt it necessary to begin the attack on Barcelona’. And after the besieged, starving for weeks had devoured the old hides that served as curtains at the forty-one gates and others, driven by the desperation and misery of war, had thrown themselves headlong from the walls, the evil enemy surrendered. And Louis celebrated ‘with a feast of thanksgiving worthy of God’, marched with the priests, ‘who preceded him and the army, in a solemn procession and amid songs of praise, entered the city gate and made his way to the church of the holy and victorious Cross.’

Genuine Christianity.

In this connection we read of Ludwig in an old Catholic standard work that ‘he was always in good spirits’, that his spirit was ‘noble’ and his heart was ‘adorned with all good habits’ (Wetzer/Welte). A bloody sword and a heart of gold is something that fits perfectly into this religion. Was it not even a distant and modest reflection of the good God and his handling of hellfire? This is how the doctor of the Church and Pope Gregory I ‘the Great’ expresses himself with his knife-sharp theology: ‘The omnipotent God, as a kindly God, takes no pleasure in the torment of the wretched; but as a just God he defines himself as uncompassionate by punishing the wicked for all eternity’.

A comfortable religion: something that works for all cases.

It was precisely with this God, kind but ‘not compassionate for all eternity’ towards the wicked—and all enemies are wicked—that all kinds of robberies and murders took place, as was already the case in the time of the Merovingians and the Pippinids, and was constantly repeated in the Christian West. And again we read:

But trusting in God’s help, our people, though greatly outnumbered, forced the enemies to flee and filled the path of the fugitives with many dead, and their hands did not cease in slaughter (et eo usque manus ab eorum caede non continuerunt) until the sun disappeared and with it the light of day and the shadows covered the earth and the bright stars appeared to illuminate the night. With the assistance of Christ, they departed from there with great joy and bringing many treasures to their own.

With Louis I (Ludwig or Ludovico Pio i.e., the Pious) ‘the Christian doctrine reached the lowest strata’ and is becoming more and more firmly established. In order that the blood of all those barbarously murdered should not splash too much, that this chronicle of cruelty should not overflow to the brim, the spiritual and divine are always emphasised with greater emphasis, only to be smeared with blood in a dignified manner later on. That is why in the same context the chorepiscopus Thegan says: ‘He never raised his voice to laughter’. And likewise: ‘When he went to church every morning to pray, he always bent his knees and touched the ground with his forehead, praying humbly for a long time and sometimes with tears.’

Louis the Pious was influenced by the clergy from his childhood. For this reason he was so early subject to the Church that, had his father not prevented him, he would have become a monk. And, as the Astronomus also celebrates after his death, ‘he was so solicitous for the divine service and the exaltation of the holy Church, that judging by his works he might be called a priest rather than a king’. Pious, super-clerical and even rather hostile to the culture imposed by his father, Ludwig not only replaced the sensual courtiers in Aachen with clerics but also expelled all prostitutes and locked his sister in a monastery.

2 replies on “Christianity’s criminal history, 173”

Pagans are always portrayed as blood thirsty, but I think the Christians have them beat by a mile. Can anyone think of any case of Pagans slaughtering others to impose their religion on them? Or slaughter a tribe simply because their Paganism was slightly different? Wars of conquest I can understand. However killing kith and kin strictly over religion seems to be a Christian thing. Or maybe it’s just an excuse to coverup wars of conquest?

Pagans never fought among themselves out of religion.

Even Pagan Rome built shrines and temples for their Celtic and Germanic citizens as to honor their religion. The temple of Nehalennia, a Germanic goddess, is a good example of it. It still exists today in The Netherlands.

Converting and destroying other religions is inherently an abrahamic thing. They cannot thrive as long as there is competition.