It is natural that he should want to do nothing to help ‘save’ a civilisation whose demise he wishes to see, and that the people who admire it should, more or less vaguely, smell the enemy in him. It is no less natural that a doctrine that runs against the tide of Time—a doctrine that preaches, in the name of a Golden Age ideal, revolt, and even violent action, against the ‘values’ of our decadent age and its institutions—should arouse his enthusiasm and secure his support: he is himself an individual of those I have called ‘men against Time’.

But why do the people who are the submissive and obedient children of our time turn out to be so dissatisfied and anxious? Why is it that this ‘progress’, in which they so firmly believe, doesn’t bring them, in the exercise of their profession, that minimum of joy without which all work is a chore?

It is because the technical environment doesn’t only act on the masses; it creates them from scratch. As soon as technical development exceeds a certain ‘critical point’, which is difficult to define, the human community, naturally hierarchical, tends to break up. Little by little it is replaced by the mass; the mass, that is to say above all the great number, with little or no hierarchy, because of unstable, shifting and unpredictable quality.

Quality is (statistically) always in inverse proportion to quantity. And the most nefarious technique from this point of view—the one most directly responsible for all the consequences of the indiscriminate formation of human masses on the surface of the globe—is undoubtedly medicine: the most harmful because it is the one that is in the most flagrant opposition to the spirit of Nature from one end of the scale of living beings; that which, instead of seeking to preserve the health, and any kind of biological priority of the strong, strives to cure diseases and prolong the lives of the weak by keeping alive the incurable, the monsters, the idiots, the insane, and all sorts of people whose removal in a society founded on sound principles would take for granted.

The result of the progress made by this technique—achieved at the cost of the most hideous experiments, practised on perfectly healthy and beautiful animals, which are tortured and dislocated, always in the name of man’s ‘right’ to sacrifice everything to his species—is that the number of men on earth is increasing in alarming proportions, while their quality decreases. You can’t have quality and quantity. You have to choose.

It is now a fact that the population of the world is growing geometrically; that, above all, the population of the hitherto ‘underdeveloped’ countries is growing faster than any other. These countries have not yet reached the technical level of the industrialised countries, but they have already been sent a host of doctors; they have already been indoctrinated into taking ‘hygienic measures’ which they didn’t know about, when they were not outright imposed on them.

As a result, the traditional occupations like working the land or various crafts are no longer sufficient to absorb the countless energies available. There will be unemployment and famine, unless mechanised industries are installed everywhere, that is to say, unless the immense majority of the population, whose numbers have quadrupled in thirty years, are turned into proletarians; unless they are torn away from their traditions, wherever they have retained any, and are forced into factories and work that, by its very nature—because it is mechanical—cannot be interesting.

Production will then skyrocket. It will be necessary to sell what has been manufactured. To do this, it will be necessary to persuade people to buy what they neither need nor want, to make them believe that they need it and to instil in them the desire for it at all costs. This will be the task of advertising.

People will fall for this deception because there are already too many of them to be moderately intelligent. It will take money for them to acquire what they don’t need, but have been persuaded to want. To earn it quickly, to spend it right away, they will agree to do boring jobs, jobs in which there is no creative element and that in a smaller society, with a slower life, nobody would want to do.

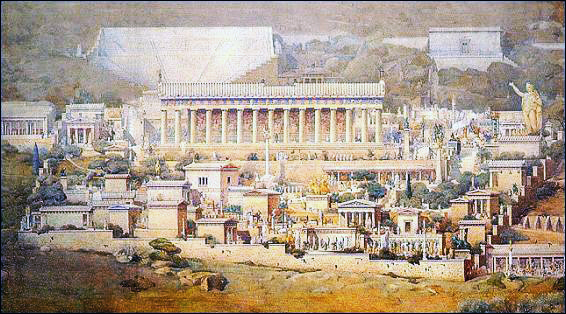

They will accept them, because technology and propaganda will have turned them into an increasingly uniform, or rather formless, multitude in which the individual exists, in fact, less and less while imagining himself to have more and more ‘rights’, and aspiring to more and more purchasable enjoyments—a caricature of the organic unity of the old hierarchical societies, where the individual thought himself nothing, but lived healthily and usefully, in his place, as a cell of a strong and flourishing body.

The key to discontent in everyday life, and especially in working life, is to be found in the two notions of multitude and haste.