Below, an abridged translation from the third volume of

Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums.

Fabrications in the New Testament

‘Forgeries begin in the New Testament era and have never ceased’.

—Carl Schneider, evangelical theologian

The error of Jesus

At the beginning of Christianity there are hardly any falsifications, assuming that Jesus of Nazareth is historical and not the myth of a god transported to the human being. However, historicity is merely presupposed here; it is, independently from some exceptions, the communis opinio (common opinion) of the 20th century. But there is no actual demonstration. The hundreds of apologetic nonsense in circulation, such as that of the Jesuit F.X. Brors (with imprimatur), are as gratuitous as brazen: ‘But where is a personality somewhere whose existence is historically guaranteed as the person of Christ? We can also mythologize a Cicero, a Caesar, even Frederick the Great and a Napoleon: but more guaranteed that the existence of Christ is not theirs’.

On the contrary, what is clear is that there is no demonstrative testimony of the historical existence of Jesus in the so-called profane literature. All extra-Christian sources do not say anything about Jesus: Suetonius and Pliny the Younger on the Roman side, Philo and, especially important, Justus of Tiberias on the Jewish side. Or they do not take into consideration, as the Testimonia (Testimony) of Tacitus and Flavius Josephus, what even many Catholic theologians admit today. Even a well-known Catholic like Romano Guardini knew why he wrote: ‘The New Testament is the only source that reports on Jesus’.

Insofar as the judgment that the New Testament and its reliability deserves, critical historical theology has shown, in a way as broad as precise, a largely negative result. According to critical Christian theologians the biblical books ‘are not interested in history’ (M. Dibelius), ‘they are only a collection of anecdotes’ (M. Werner), ‘should be used only with extreme caution’ (M. Goguel), are full of ‘religious legends’ (Von Soden), ‘stories of devotions and entertainment’ (C. Schneider), full of propaganda, apologetics, polemics and tendentious ideas. In short: here everything is faith, history is nothing.

This is also true, precisely, about the sources that speak almost exclusively of the life and doctrine of the Nazarene, the Gospels. All the stories of Jesus’ life are, as its best scholar, Albert Schweitzer, wrote, ‘hypothetical constructions’. And consequently, even modern Christian theology, all of which is critical and does not cling to dogmatism, puts into question the historical credibility of the Gospels; arriving unanimously at the conclusion that, regarding the life of Jesus, we can find practically nothing. The Gospels do not reflect, in any way, history but faith: the common theology, the common fantasy of the end of the 1st century.

Therefore, in the beginnings of Christianity there is neither history nor literary fabrications but, as the central issue, its true motive, error. And this error goes back to none other than Jesus.

We know that the Jesus of the Bible, especially the Synoptic, is fully within the Jewish tradition. He is much more Jewish than Christian. As to the others, the members of the primitive community were called ‘Hebrews’. Only the most recent research calls them ‘Judeo-Christian’ but their lives were hardly different from that of the other Jews. They also considered the sacred Jewish Scriptures as mandatory and remained members of the synagogue for many generations.

Jesus propagated a mission only among Jews. He was strongly influenced by the Jewish apocalyptic—and this influenced Christianity mightily. Not in vain does Bultmann has one of his studies with the title Ist die Apokalyptik die Mutter der christlichen Theologie? (Is the apocalyptic the mother of Christian theology?). In any case, the New Testament is full of apocalyptic ideas and such influence has its mark in all its steps. ‘There can be no doubt that it was an apocalyptic Judaism in which the Christian faith acquired its first and basic form’ (Cornfeld / Botterweck).

But the germ of this faith is Jesus’ error about the imminent end of the world. Those beliefs were frequent. It did not always mean that the world would end, but perhaps it was the beginning of a new period. Similar ideas were known in Iran, in Babylon, Assyria and Egypt. The Jews took them from paganism and incorporated them into the Old Testament as the idea of the Messiah. Jesus was one of the many prophets—like those of the Jewish apocalypses, the Essenes, John the Baptist—who announced that his generation was the last one. He preached that the present time was over and that some of his disciples ‘would not taste death until they saw the kingdom of God coming’; that they would not end the mission in Israel ‘until the Son of Man arrives’; that the final judgment of God would take place ‘in this same generation’ which would not cease ‘until all this has happened’.

Although all this was in the Bible for a millennium and a half, Hermann Samuel Reimarus, the Hamburg Orientalist who died in 1768 (whose extensive work, which occupied more than 1,400 pages, was later published in parts by Lessing), was the first to recognise the error of Jesus. But until the beginning of the 20th century the theologian Johannes Weiss did not show the discovery of Reimarus. It was developed by the theologian Albert Schweitzer.

The recognition of Jesus’ fundamental error is considered the Copernican moment of modern theology and is generally defended by the critical representatives of history and the anti-dogmatics. For the theologian Bultmann it is necessary ‘to say that Jesus was wrong in waiting for the end of the world’. And according to the theologian Heiler ‘a serious researcher discusses the firm conviction of Jesus in the early arrival of the final judgment and the end’.

But not only Jesus was wrong but also all Christendom since, as the archbishop of Freiburg, Conrad Gröber (a member promoter of the SS) admits, ‘it was contemplated the return of the Lord as imminent, as is testified not only in different passages in the epistles of St. Paul, St. Peter, James and in the Book of Revelation; but also by the literature of the Apostolic Fathers and the Proto-Christian life’.

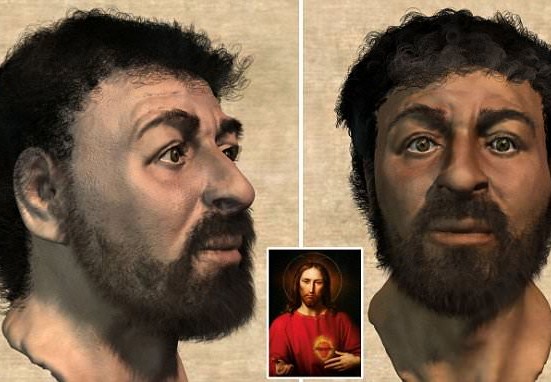

(Note of the Ed.: The face that Richard Neave constructed from skulls of typical 1st century Palestinian Jews suggests that Jesus, if he existed, must have differed significantly from the traditional depictions in Western art, which invariably ‘Nordicize’ the Semites.)

(Note of the Ed.: The face that Richard Neave constructed from skulls of typical 1st century Palestinian Jews suggests that Jesus, if he existed, must have differed significantly from the traditional depictions in Western art, which invariably ‘Nordicize’ the Semites.)

Marana tha (‘Come, Lord’) was the prayer of the first Christians. But as time passed without the Lord coming; when doubts, resignation, ridicule and discord were increasing, the radicalism of Jesus’ affirmations had to be gradually softened. And after decades and centuries, when the Lord finally did not arrive, the Church converted what in Jesus was a distant hope, his idea of the Kingdom of God, into the idea of ‘the Church’. The oldest Christian belief was thus replaced by the Kingdom of Heaven: a gigantic falsification; within Christian dogma, the most serious one.

The belief in the proximity of the end decisively conditioned the later appearance of the Proto-Christian writings in the second half of the 1st century and in the course of the 2nd century. Jesus and his disciples—who expected no hereafter and no state of transcendental bliss but the immediate intervention of God from heaven and a total change of all things on Earth—naturally had no interest in taking notes, writings, or books; for whose writing they were not even trained.

And when the New Testament authors began to write, they softened the prophecies of Jesus of a very imminent end of the world. The Christians did not live that end and this is why questions arise in all ancient literature. Scepticism and indignation spread: ‘Where, then, is his announced second coming?’ says the second Epistle of Peter. ‘Since the parents died, everything is as it has been since the beginning of creation’. And also in Clement’s first epistle the complaint arises: ‘We have already heard this in the days of our fathers, and look, we have aged and none of that has happened to us’.

Voices of that style arise shortly after the death of Jesus. And they are multiplied in the course of the centuries. And here there is how the oldest Christian author, the apostle of the peoples, Paul, reacts. If he first explained to the Corinthians that the term ‘had been set short’ and the ‘world is heading to the sunset’, ‘we will not all die, but we will all be transformed’—later he spiritualised the faith about the final times that, from year to year, became increasingly suspicious. Paul thus made the faithful internally assume the great renewal of the world, the longing for a change of eons, was fulfilled through the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Instead of the preaching of the kingdom of God, instead of the promise that this kingdom would soon emerge on Earth, Paul thus introduced individualistic ideas of the afterlife, the vita aeterna (eternal life). Christ no longer comes to the world but the believing Christian goes to him in heaven! Similarly, the gospel authors who write later soften Jesus’ prophecies about the end of the world and make the convenient corrections in the sense of a postponement. The one that goes further is Luke, who substitutes the hopeful belief for a history of divine salvation with the notion of previous stages or intermediate steps.

______ 卐 ______

Liked it? Take a second to support this site.

8 replies on “Christianity’s Criminal History, 81”

Most Christians ignore that the order of the New Testament texts in the Christian Bibles is extremely deceiving. One of the keys to understanding it is to put the oldest NT writings first (e.g., the Pauline epistle that Deschner cites above) and then proceed chronologically. See for example what I wrote five months ago:

https://westsdarkesthour.com/2018/05/07/about-the-risen-jesus/

the power of belief: humans prefer gigantic falsification to admitting error.

Indeed!

The gospel accounts of Jesus’ death aren’t even in agreement. In Matthew and Mark, Jesus’ last words are a sniveling “God, God, why have you forsaken me?”, which seems to me to indicate that he expected to be rescued from the cross at that moment, quite in keeping with his other pronouncements that paradise would be established on earth within the current generation. Contradicting this, in Luke, his last words are given as a pious “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” In John, he simply says “It is finished.” So much for the Bible being the inerrant word of God.

Another oddity, peculiar to Matthew 27:51, is the account of numerous corpses rising from the dead at the moment of Jesus’ death.

You would certainly think such a memorable event would have been noticed and recorded by historians — but just like the historical Jesus, no such luck. Curious.

The explanation is that the evangelists themselves, contra traditional church teaching, had different theologies. I’ve already quoted Randel Helms in this site. Here we go again:

Gospel Fictions, chapter “The Passion Narratives”.

If the gospels Mark and Matthew are fiction though, entirely unrelated to any reality other than theological, it seems odd that Jesus, the hero of the story, would be made to die sniveling; and this particularly since his words seem to confirm that his prophecy of the imminent coming of paradise on earth was in error. In the ancient world, Socrates was held up as a secular sort of Jesus-figure, one who died bravely, and very much superior to Jesus in that regard. So this humiliating death is difficult to explain if, as some maintain, all of this tale was concocted as a plot, and part of a propaganda campaign avant la lettre. For the Romans “he died well” was high praise, while the opposite was thought to be a disgrace. Why would propagandists think Romans would admire a failed prophet who died a cowardly death?

As I said in other threads, I don’t hold strong opinions about either the quest of a ‘historical Jesus’ or the ‘100% fictional Jesus’ stance, because the subject itself is a trap: it enslaves us to our parental introjects. So what Helms (a proponent of ‘it’s all fiction’) says is not necessarily what I believe. But Helms’ book is interesting.

After many years, tonight I reread some passages of a book I purchased in 1986 when it was warm from the press; so my copy is a hardcover. In The First Coming Thomas Sheehan tries to make a sculpture of the historical Jesus from a rough block of NT marble, what Hoffmann calls the ‘Platonic fallacy’. However, Sheehan (wiki article here) is very erudite of the literature and his mortal Jesus is not so implausible. For those who are curious about the scholarly literature I’ve been advertising here, Sheehan’s book (online version here) could be palatable for the American reader. His speculations about how the Easter myth originated are interesting.

Again—just interesting—, not necessarily what I believe.

https://youtu.be/_FXdMkFomBk

A great documentary on Biblical errancy.

I heard it said that ‘Kingdom of God’ was simply a 1st-century term for an earthly restored Davidic Kingdom. Jews, esoterically, see themselves as G-d, so their Kingdom would be, therefore, “The Kingdom of God.”

Similarly with “son of God.” All this really meant was “Son of Judea;” ” Son of Israel.”

Jewish theology is only concerned with this world. Christians supernaturalise what is essentially an atheistic religion.