If you look into an abyss, the

abyss, likewise, looks into you.

This self-addressed pæan of intoxicated happiness is, I know, regarded by modern physicians as a morbid euphoria, as the last pleasure in a decaying brain, as the stigma of that megalomania which is characteristic of the early stage of paralytic dementia. But Nietzsche talks clearly and incisively amid the ardours of intoxication. No other mortal, perhaps, has ever in full awareness and without a trace of giddiness leaned so far and seen so clearly over the edge of the precipice of lunacy.

No doubt the light that sparkles here is a perilous one. It has the phantasmal and morbid luminosity of a midnight sun glowing red above icebergs; it is a northern light of the soul whose unique splendour makes us shudder. It does not warm us, it terrifies us. It does not dazzle, but it slays. He is not carried away as was Hölderlin by an obscure rhythm of feeling, is not overwhelmed by the onrush of melancholy. He is scorched by his own ardours, is sunstruck by his own rays, is affected by a white-hot and intolerable cheerfulness. Nietzsche’s collapse was a sort of carbonization in his own flames.

He commanded the German emperor to go to Rome in order to be shot; he summoned the European powers to take united military action against Germany, to encircle his fatherland in a ring of iron. Never did apocalyptic wrath shout more savagely into vacancy, never did so glorious presumption scourge a mind beyond earthly bounds. His words issued like hammer-blows striving to demolish the edifice of established civilisation. The Christian era was to cease with the publication of his Antichrist, and a new numbering of the years was to begin.

“No one has written, felt, suffered in such a manner before; the sufferings of a god, a Dionysius.” These words, penned when his mental disorder had already begun, are painfully true. The little room of the fourth floor, and the hermitage of Sils-Maria, not only sheltered the man Friedrich Nietzsche whose nerves were breaking under the strain, but also served as the places from which were issued a marvellous message to the dying century. The Creative Spirit had taken refuge beneath the attic roof heated by the southern sun, and was bestowing its entire wealth upon a timid, neglected, and lonely being, bestowing far more than any isolated person could sustain.

Within those narrow walls, wrestling with infinities, the poor mortal senses were stumbling and groping amid the lightening-flashes of revelation. Like Hölderlin, he felt that a god was revealing himself, a fiery god whose radiance the eyes could not bear and whose proximity was scorching. Again and again the cowering wrench raised his head and attempted to look upon the countenance of this deity, his thoughts running riot the while.

Was not he who felt and wrote and suffered such unthinkable things, was not he himself God? Had not a god reanimated the world after he, Nietzsche, had slain the old god? Who was he? Who was Nietzsche? Was Nietzsche the Crucified; the dead god or the living one; the god of his youth, Dionysius; or both Dionysus and the Crucified—the crucified Dionysius?

More and more confused grew his thoughts; the current roared too loud beneath the superfluity of light. Was it still light? Had it not become music? The narrow room on the fourth floor in the Via Carlo Alberto began to intone; the shining spheres made music; all heaven was aglow. What wonderful music! Tears tricked down his face, warm tears. What sublime tenderness, what auspicious happiness! And now, what lucidity! In the street, everyone smiled at him in friendly fashion; they stood up to greet him; they made obeisance to him, the slayer of gods; they were all so delighted to see him. Why? Why?

He knew. Antichrist had appeared upon earth, and men acclaimed him with hosannas. The world hummed with jubilation, was full of music. Then suddenly the tumult was stilled. Something, someone fell down. It is he, himself, in the street, in front of the house where he lodged. He was picked up. He found himself back in his room.

Had he been asleep for a long time? It seemed very dark. There was the piano. Music! Music! Then, unexpectedly, people appeared in the room. Surely one of them must be Overbeck. But Overbeck is in Basel; and where is he, Nietzsche? He no longer remembers. Why does the company look at him so strangely, so anxiously? He is in a train, rattling along the rails, and the wheels are singing; yes, they are singing the “Gondolier’s Chanty,” and he joins in, signs in an interminable darkness.

He is in a strange room, and always it is dark. No more sunshine, no light at all, either within or without. People talk in the room. A woman among them, surely it is his sister? He had thought she was travelling. She reads aloud to him, now from one book, now from another. Books? “Was not I once a writer of books?” Comes a gentle answer, but he cannot understand. One in whose soul such a hurricane has raged grows deaf to ordinary speech. One who has gazed so intently into the eyes of the daimon is henceforth blinded.

6 replies on “Dance over the abyss”

the language in these excerpts is excellent, this is great stuff. i recall hearing about Nietzsche un fettering horses in his maddness and telling them that they were free from slavery, etc. etc. as a child i was a admirer of the hollywood jewish film “ghostbusters” wherein the actor rick moranis re-enacts an ode (maybe only i saw the connection) to the great german when he is possessed by a sumerian demon and he also unshakles a horse with similar words.

Yes: it greatly impressed me when I read this old translation I photocopied in the Houston University library seventeen years ago.

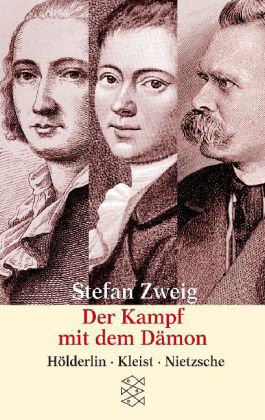

Awesome book by Zweig! Thanks for sharing this excerpt. I wrote an article about it and at the end of it there’s a link to this post – here it is, if you wanna check it out: [link]

Yes, IMO the best psycho-biography that came out from Zweig’s pen.

Yeah, I liked a lot his book on Montaigne also! Zweig’s prose is really powerful, filled with insights, and beautifully written…

Have you read all of my excerpts?

http://cienciologia.wordpress.com/category/the-struggle-with-the-daimon/