The profession called psychiatry

The first thing to keep in mind when a loved one is in crisis is the Hippocratic oath of doctors: do no more harm. Unfortunately, it is precisely the doctors who violate that oath, since the crises of the spirit should never be the province of the doctor.

Carlos Torre was electro-shocked in Monterrey when he lived with his three brothers, all doctors. I read this in the book 64 Variaciones Sobre un Tema de Torre by Germán de la Cruz. I was so intrigued that I made some inquiries. I spoke with Jorge Aldrete, a bridge and chess fan from Monterrey based in Mexico City, who had sold me several imported chess sets. Both Aldrete and Ferriz suggested that I contact Arturo Elizondo in Monterrey. On April 24, 2004, I spoke with Mr Elizondo, who graciously answered my questions. This man of more than eighty years was neither more nor less an eyewitness of the electroshocks to Torre. When I asked him if what de la Cruz said in his book was reliable, he replied: ‘I am sure because to control his physicality’ he was ‘by his side’ during electroconvulsive therapy. I asked him what the symptoms were so that they took such a drastic measure with the Yucatecan chess master. Elizondo replied: ‘The only thing, he was stubborn but he wasn’t aggressive and nothing like that’. Elizondo only slightly disagreed with de la Cruz’s version insofar as he affirmed that the brothers weren’t directly responsible for the commitment. ‘It was the nephew, surnamed Torre’, a Masonic grand master and colleague of Elizondo at the Nuevo León lodge. According to Elizondo, this happened in 1957 in the psychiatric ward of the General Hospital of Monterrey. Due to Torre’s ‘excitatory stage’ to use Elizondo’s expression, the diagnosis was manic-depressive, which is now called bipolar disorder. It had been the arousal phase of his manic-depressive crisis when they applied electroshocks to calm him down.

Universities teach kids psychiatric treatments, such as electroshock, as if they were the praxis of real medical science. No wonder that, being Elizondo a chemist sympathetic to medicine, he repeated to me what is claimed at the universities: that Torre-type excitations are of a ‘neurological nature’, a claim that Elizondo repeated several times during our telephone conversation. The truth is that, without any laboratory testing, psychiatrists rule out psychogenic hypotheses of delusions (see once again my anti-psychiatric site whose address appears on page 3 of this book). He also told me that electroshocks are ‘a very noble therapy’ because it ‘completely relaxes’ the excited. Elizondo participated in the coercive relaxation of Torre, in which he even helped hold him down. He even confessed to me, ‘One or two days I gave him accommodation, then he left with his nephew’. But what Elizondo ignored is that electroshock is a crime. This electric hammer blow to the head frequently erases part of the memory of the people who receive it. One of the cases I mention on my antipsychiatric site is that of a graduate student who, after she was shocked from depression, forgot what she had learned in college. We can imagine the handicap that the ‘therapy’ represented for her career. In Torre’s time there was the aggravating circumstance that it was common to perform marathon electroshock sessions: a practice that some call electrical lobotomy. We can imagine how this barbaric practice could have diminished Torre’s intellectual capacity for chess. Do you remember the scene of the electroshock applied to the character played by Jack Nicholson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest?

This type of assault on healthy brains (like the character played by Nicholson, the electro-shocked folk had a healthy brain before ‘therapy’) continues to be performed in Mexico. This is done even in the largest psychiatric hospital in the nation: the Fray Bernardino Álvarez Hospital in Tlalpan, where students do their internships. In 1960, three years after his experience in Monterrey, Torre was once again harassed by his sponsors and by psychiatrists. When he lived in Mexico City, he was committed for a few days at the Sanatorio Floresta, which was in San Ángel, under the care of psychiatrist Alfonso Millán. Alfonso Ferriz told me this personally, who in his splendid naivety paid for the commitment. The Floresta psychiatric hospital no longer exists, but as I indicate on my aforementioned website, on November 25, 1970 an article appeared in Siempre! entitled ‘A season in hell’ written by two sane young men who were interned at Floresta. The authors of the article reveal that a grandson of Victoriano Huerta was lobotomised and confined there: ‘Before, he was very aggressive until he had a lobotomy. He now is a child. At meals he twists around on the chair, he eats desperately. While eating he drives the flies away from the table’. Ferriz and Elizondo acted in good faith, but the road to hell is paved with good intentions. According to Ferriz himself in one of the interviews recorded by Obregón, Torre felt resented with him for life after the outrage of which he was a victim in the psychiatric hospital. In fact, Torre didn’t see Ferriz again until the latter visited Mérida.

In his book, Gabriel Velasco, ignoring what psychiatry is, after the New York crisis wrote that Torre ‘needed medical care’. There were still no electroshocks in the 1920s. But if Velasco refers to some other psychiatric therapy that was applied to him, this way of using language (‘medical care’) is a euphemism for medical crime. In the prologue to Velasco’s book, Jesús Suárez praises that Velasco has omitted all speculation about Torre’s ills. The truth is that it was pure intellectual cowardice, both by Velasco and Suárez, to have omitted that he was electro-shocked in Monterrey; that in Mexico he was admitted to the Floresta, and that he resented Ferriz for life.

Those who knew him were struck by the fact that Carlos Torre was a very affectionate person with people. He called them all angelito, padrecito, madrecita (little angel, little father, little mother): expressions that portray the goodness of his character. Let’s put ourselves in the master’s shoes for a moment. Imagine that we speak in sweet Mexican diminutives. How would we feel after the involuntary commitment by our loved ones? What would we feel after the assault on the brain in Monterrey? In addition to the intellectual loss, wouldn’t it be an attack on one’s dignity and self-esteem? How would our self-image look after the attack?

Although Ferriz assured me that he wasn’t electro-shocked in Mexico City, they administered him psychiatric drugs at the Floresta. I wonder if Torre was tormented there with drugs called neuroleptics: a ‘hell’ as described by the authors of Siempre! According to the words of Ferriz himself, which I wrote down in an interview at his house in March 2004, I guess that Torre was sane when committed. Ferriz confessed to me: ‘But also, he didn’t seem crazy! It was hard to get what was wrong with him’. Like the ‘stubbornness’ Elizondo spoke of, Ferriz interprets anger as a mental disorder. I didn’t argue with Ferriz or Elizondo. But after the interview with the former I wondered what they had done to Torre in the Floresta, the psychiatric hospital that had Huerta’s lobotomised grandson in custody. And by the way: was this guy lobotomised there? Nobody asks questions of this kind in Mexico for the simple reason that it’s difficult to imagine that a pseudoscience is taught in universities. It is a stupendous irony that in Mexico the medical institution had to have arisen precisely in the same building of the Inquisition of New Spain: the palace of the old Faculty of Medicine.

This brief book is far from my extensive treatise on psychiatry that can be read on the internet. But just to give an idea of what I am talking about, I will mention a chilling fact: In the 21st century, lobotomies continue to be performed in Mexico and the rest of the world. The fact that defenceless citizens are currently electro-shocked and lobotomised, as they did to the character that Nicholson played in One Flew, may seem incredible to us. But a little story will shed some light on this matter.

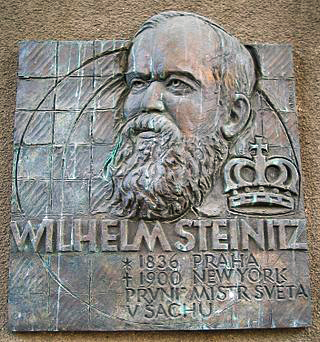

For three centuries, Western civilisation has been cruel to people suffering from spiritual crises. Although the individual who suffers a sudden crisis doesn’t harm anyone—let’s take as a paradigm the buffoonery of imitating St. Francis on a public streetcar—the brain of he who suffers the crisis is damaged by society. From the origins of the mental institution at Bedlam in London and general hospitals in France, the treatment of the individual in crisis has been simply to torture him with various techniques (see ‘From the Great Confinement to chemical Gulag’, pages 143-166 in my book Daybreak). Although these tortures have nothing to do with real medical necessity, they were given a scientific lustre in the 19th century for public acceptance. I wonder what they did to Steinitz in one of those so-called hospitals. In his time, psychiatrists hadn’t devised electroshock and lobotomy, techniques that directly damage the brain, but they did devise some torments that broke the spirit of the person in crisis. In 19th-century nursing homes, beatings and chains were a thing of every day. There were even torture devices. I have not read the biography of Steinitz written by Bachmann. I suppose the Kneip technique applied on Steinitz, an extreme regimen of ice water baths, was involuntary.

Iatrogenesis is the stupid attempts to heal by doctors that produce new and more serious disorders than the existing ones. I believe that Steinitz’s illusory ideas at the end of his life, such as his belief that he could move chess pieces without touching them, were aggravated by psychiatric iatrogenesis.

The Kneip torment is discontinued in psychiatry. Due to modern technology, since the 1930s medical science has progressed from tormenting Steinitz’s body to directly assaulting the brain—what they did to Torre. In addition to electroshocks, chemical lobotomisers that are administered to those who cross through crises like the one Torre suffered are currently very fashionable. With a prescription, about twenty of these chemicals are sold in Mexico: Clopsine, Ekilid, Fluanxol, Flupazine, Geodon, Haldol, Haloperil, Largactil, Leponex, Leptopsique, Melleril, Piportil, Pontiride, Rimastine, Risperdal, Semap, Seroquel, Sinogan, Siqualine, Stelazine, and Zyprexa. Aliosha Tavizon, with whom I used to speak at the Gandhi Cafeteria and who in his category won the Carlos Torre Tournament in 2003, was given one of these crap drugs due to an unreciprocated love that temporarily unhinged him. For months he had a crooked neck and many other muscles in his body. To speak to him, he had to position his torso in profile: a tardive dystonia that may have been irreversible. Under no circumstances, not even during flowery psychoses, should an individual ingest any of these dangerous neurotoxins. Fortunately, there are principled psychiatrists, like Peter Breggin, who denounce the crime of prescribing disabling drugs in their profession.

The West, and especially the United States, have fallen into the cognitive error of addressing any psychological disturbance from a biological POV, ignoring the humanities. I do not think that this pseudoscience will be repudiated soon despite the iatrogenesis it produces. In my treatise I show, in a nutshell, that the profession doesn’t pass the falsifiability test devised by Karl Popper that distinguishes between science and pseudoscience, and that those who finance psychiatric ‘science’ in journals are the same companies that manufacture the drugs mentioned above. The academia itself has been corrupted by Big Pharma. If the reader doesn’t want to read my book because I am not an established author, read Mad In America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and The Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill (Cambridge: Perseus, 2001). Robert Whitaker, the author, won the Pulitzer Prize for medical matters.