“After the next European war, people will understand me.” Such is the prophetic utterance that shines conspicuously forth from among Nietzsche’s last writings. In very truth, the real significance, the historical necessity of this seer is made plain to us only in relation to the tensed, unstable, and dangerous condition of our world at the turn of the century.

In this sensitive, who transformed every atmospheric convulsion from nerve to spirit, from intimation into word, there occurred a foreboding discharge of all the tensions of the morally obtuse Europe. There was a cataclysm in Nietzsche’s mind as a presage of the most terrible cataclysm in human history. His “far-thinking” vision glimpsed the crisis while others were comfortably warming their heads before the agreeable fires of well-turned phrases. He discerned the causes of what was about to happen: “The national cardiac pruritus and the blood-poisoning thanks to which, throughout Europe, nation shuts itself off from nation as if they were quarantining against one another’s plagues.” He saw the “nationalism as of horned cattle.”

Wrathfully he predicts catastrophe in view of the convulsive endeavours “to eternalize particularism throughout Europe” and to defend a morality established upon egoistic interests and upon business. In letters of fire upon the wall he wrote: “This absurd state of affairs must speedily be brought to an end.” No one heard more plainly than did Nietzsche the ominous cracking in the edifice of European society; no one, in a time of unwarranted optimism and self-satisfaction, sounded so loudly as he the summons to fight. A new and mighty order was about to begin. Now at length we know it, as he knew it decades ago. Such agonizing foresight was his greatness and his heroism; and there is a spiritual truth underlying the belief of simple souls that before wars and crises comets pursue their erratic course athwart the sky. He alone recognized how frightful a hurricane was about to disturb our civilisation.

But it is the perennial tragedy of the spirit that what it perceives in its higher, more luminous spheres can never be communicated to those who dwell in the heavier atmosphere upon the lower levels; that the present never grasps what is impending, is never able to read the message of the skies. Even the most translucent genius of the nineteenth century could not speak plainly enough to enable his contemporaries to understand him. No more was vouchsafed to him than the cry of warning which was incompressible to his contemporaries. Then his mind gave way.

“There are no heroic ages, but solely heroic persons.” It is the individual who achieves independence within the world, and for himself alone. Nietzsche’s independence did not therefore transmit, as scholastics declare, a doctrine, but, rather, an atmosphere—the limpid and passionate atmosphere of a daimonic nature.

Just as, in the domain of natural forces, there is need at times for whirlwinds wherein the excess of energy rises in revolt against stability, so likewise, now and again, in the realm of mind there is need for a daimonic being whose transcendent powers shall make him the spearhead of a revolt against the triviality of habitual thought and the monotonousness of conventional morality. There is need of a man who will embody the forces of destruction and who will destroy himself likewise.

____________

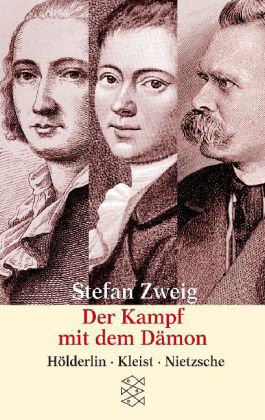

After a few more words, Zweig’s essay on Nietzsche ends.

In all of these entries I only typed those paragraphs

which struck me the most.

2 replies on “The teacher of freedom”

Stefan Zweig was a Jew – and a very perceptive/gifted person.

A Jew that Hitler allowed to write the libretto of a Richard Strauss opera.