What he reproached most of all, it seems, was the fact that Christianity alienated his followers from Nature; that it inculcated in them a contempt for the body and, above all, presented itself to them as the ‘consoling’ religion par excellence: the religion of the afflicted; of those who are ‘toiled over and burdened’ and don’t have the strength to bear their burden courageously; of those who cannot come to terms with the idea of not seeing their beloved ones again in a naïvely human Hereafter. Like Nietzsche, he found it to have a whining, servile rotundity about it, and considered Christianity inferior to even the most primitive mythologies, which at least integrate man into the cosmos—all the more inferior to a religion of Nature, ancestors, heroes and of the national State such as this Shintoism, whose origin is lost in the night of prehistory, and which his allies, the Japanese, had had the intelligence to preserve, by adapting it to their modern life.[1]

And in contrast, he liked to evoke the beauty of the attitude of his followers who, free of hope as well as fear, carried out the most dangerous tasks with detachment. ‘I have’, he said on December 13, 1941 in the presence of Dr Goebbels, Alfred Rosenberg, Terboven and others, ‘six SS divisions composed of men who are absolutely indifferent in matters of religion. This doesn’t prevent them from going to their deaths with a serene soul’.[2]

Here, ‘indifference in matters of religion’ just means indifference to Christianity and, perhaps, to all religious exotericism; certainly not indifference to the sacred. Quite the contrary! Because what the Führer reproached Christianity, and no doubt any religion or philosophy centred on the ‘too human’, was precisely the absence in it of that true piety which consists in feeling and adoring ‘God’—the Principle of all being or non-being, the Essence of light and also of Shadow—through the splendour of the visible and tangible world; through Order and Rhythm and the unchanging Law which is its expression: the Law which melts opposites into the same unity, a reflection of unity in itself. What he reproached them for was their inability to make the sacred penetrate life, all life, as in traditional societies.

And what he wanted—and, as I shall soon try to show, the SS must have had a great role to play here—was a gradual return of the consciousness of the sacred, at various levels, in all strata of the population. Not a more or less artificial resurgence of the cult of Wotan and Thor (the Divine never assumes again, in the eyes of men, the forms it once abandoned) but a return of Germany and the Germanic world in general, to Tradition, grasped in the Nordic manner, in the spirit of the old sagas including those which, like the legend of Parsifal preserved, under Christian outward appearances, the unchanged values of the race; the imprint of eternal values in the collective soul of the race.

______ 卐 ______

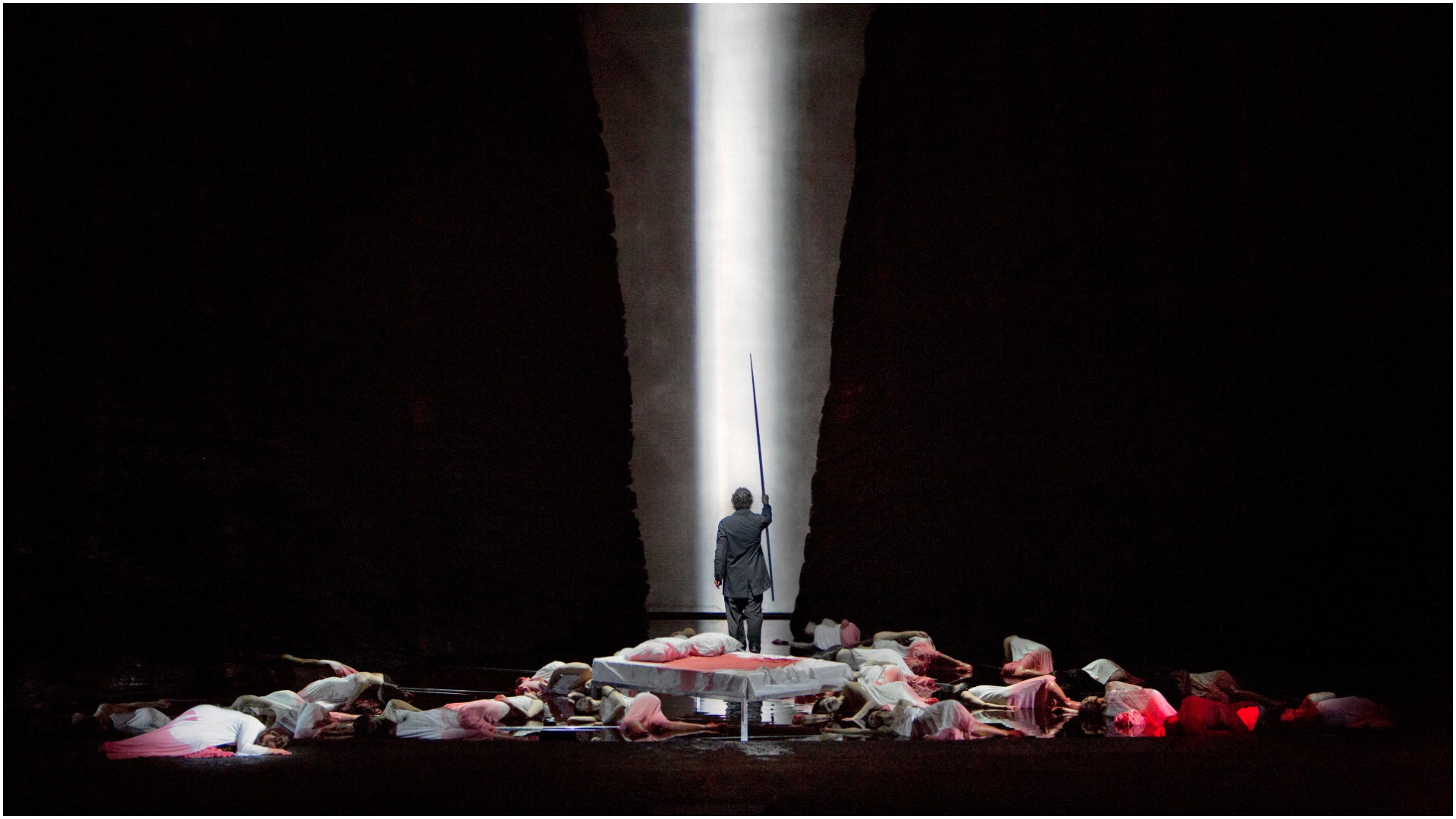

Editor’s note: Last year I wrote: ‘Musically, I think Parsifal is Wagner’s most accomplished work. The overtures of each of the three acts, as well as the magnificent music when Gurnemanz takes Parsifal into the castle in the first act; the background music and the voices by the end of the discussion between Parsifal and Kundry in the second act, and let’s not talk about the Good Friday music in the third act, are the most glorious and spiritual I have ever listened. No wonder why Max Reger (1873-1916) confessed: “When I first heard Parsifal at Bayreuth I was fifteen. I cried for two weeks and then became a musician”.’

Editor’s note: Last year I wrote: ‘Musically, I think Parsifal is Wagner’s most accomplished work. The overtures of each of the three acts, as well as the magnificent music when Gurnemanz takes Parsifal into the castle in the first act; the background music and the voices by the end of the discussion between Parsifal and Kundry in the second act, and let’s not talk about the Good Friday music in the third act, are the most glorious and spiritual I have ever listened. No wonder why Max Reger (1873-1916) confessed: “When I first heard Parsifal at Bayreuth I was fifteen. I cried for two weeks and then became a musician”.’

______ 卐 ______

He wanted to restore to the German peasant ‘the direct and mysterious apprehension of Nature, the instinctive contact, the communion with the Spirit of the Earth’. He wanted to scrape off ‘the Christian varnish’ and restore to him ‘the religion of the race’ [3] and, little by little, especially in the immense new ‘living space’ which he dreamed of conquering in the East, to remake from the mass of his people a free peasant-warrior people, as in the old days when the immemorial Odalrecht, the oldest Germanic customary law, regulated the relations of men with each other and with their chiefs.

It was from the countryside, which, he knew, still lived on, behind a vain set of Christian names and gestures, pagan beliefs from which he intended one day to evangelise those masses in the big cities: the first victims of modern life in whom, in his own words, ‘everything was dead’. (This ‘everything’ meant for him ‘the essential’: the capacity of man, and especially of the pure-blooded Aryan, to feel both his nothingness as an isolated individual and his immortality as the repository of the virtues of his race, his awareness of the sacred in everyday life.)

He wanted to restore this sense of the sacred to every German—to every Aryan—in whom it had faded or been lost over the generations through the superstitions spread by the churches as well as by an increasingly popularised false ‘science’. He knew that this was an arduous and long-term task from which one could not expect spectacular success, but whose preservation of pure blood was the sine qua non of accomplishment—because, beyond a certain degree of miscegenation (which is very quickly reached) a people is no longer the same people.

___________

[1] Ibid., p. 141

[2] Libres propos sur la Guerre et la Paix, translation, p. 140.

[3] H. Rauschning, Hitler m’a dit, treizième édition française, p. 71.