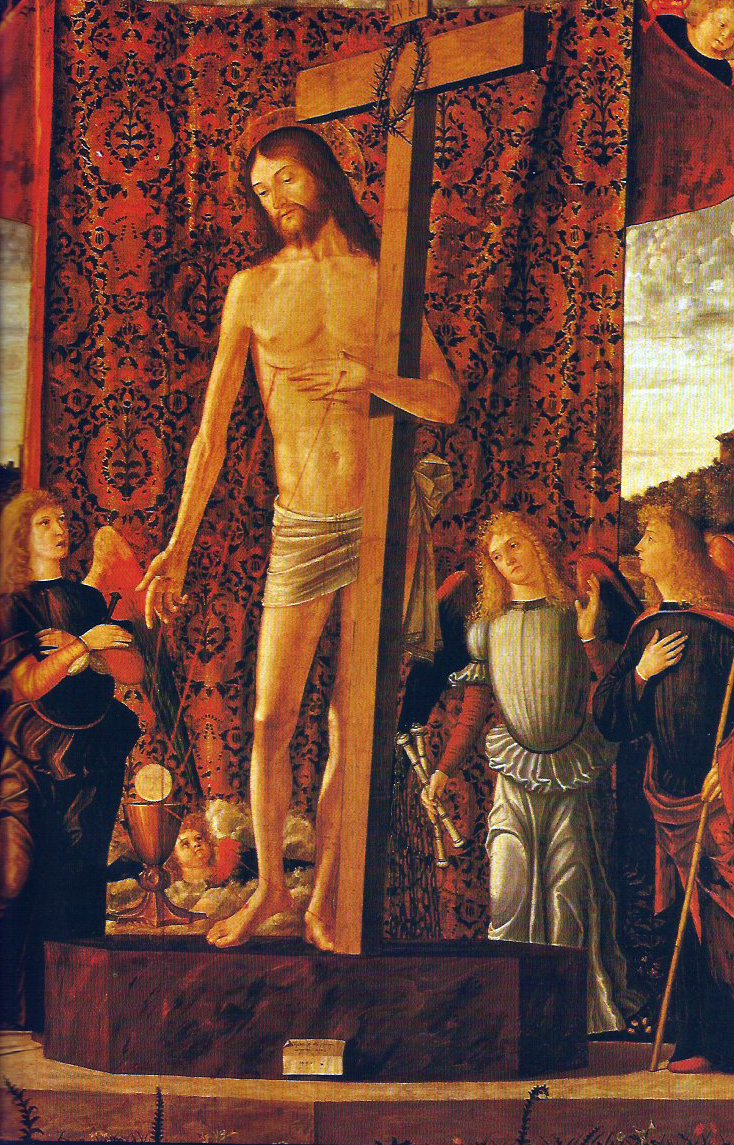

Christ Between Four Angels, by Vittore Carpaccio in the museum of Udine, northern Italy, is a mystical representation of the Passion (the fourth angel, also blond, at the extreme left, is missing in this detail of the 1496 painting).

Christ Between Four Angels, by Vittore Carpaccio in the museum of Udine, northern Italy, is a mystical representation of the Passion (the fourth angel, also blond, at the extreme left, is missing in this detail of the 1496 painting).

The blood of the crucified Jew flows from all his wounds and concentrates on the bread and chalice of the Eucharist: a true memorial to the Passion of the most famous Jew in history. Notice that he has dark hair and the angels who adore him are blond. The angels contemplate the scene and celebrate this continuity between the Passion and the Sacrament that most Christians celebrate every day.

In ‘The Saxon Savior: Converting Northern Europe’, that recounts how Greco-Romans committed the horrible sin of miscegenation, Ash Donaldson said:

______ 卐 ______

The “good news” in the Roman Empire

Two distinct cultural zones of the Mediterranean had emerged well before that division found political expression in the division of the Roman Empire. In the east, Greek was the lingua franca—so much so, that Jews living in Alexandria did not even understand Hebrew anymore, making it necessary to translate the Old Testament into Greek. A thin veneer of debased Greek culture and language lay atop this simmering racial stewpot, the final fruit of Alexander’s dream. In the west, it was a debased version of Roman culture and language that provided a semblance of cultural unity. Yet here, too, the process of urbanization, ethnic mixing, and erosion of local identities was well underway, only less advanced, depending on how recently a land had been conquered by Rome’s legions.

It was to the denizens of the Mediterranean’s tenement-crowded cities that Christianity made its primary appeal, far more so than any other foreign cult. People who lacked any sense of tribal identity, community, or even family responded well to a religion that offered instead a tribe of the elect, a community of faith, and even a substitute family to replace the old one, replete with “brothers” and “sisters.”

The cities St. Paul visited in his missionary travels and to which he wrote—Corinth, Thessalonica, and Athens—were no more necessarily Greek than New York City is Dutch because Dutchmen lived there three hundred years ago. He and the authors of the Gospel accounts wrote in Greek for the same reason that a rapper will employ English today: because that is the language his people have come to speak, and because he will reach a larger audience with it. Such use does not imply that the rapper is Anglo-Saxon.

Three centuries after its founding, Christianity remained an overwhelmingly urban religion. It made its greatest strides in areas where the polis, and all that concept entailed, was weakest or non-existent. The very origin of the word “pagan” indicates how little success Christianity had in the rural areas, where identity and tradition held out longer. This word originates in the Latin word pagus, which originally denoted a rural district, sort of like a modern county but culturally whole and readily identifiable by all those around them as distinct—in other words, very much like the Greek polis, with no urban connotation whatsoever.

From this, the Romans derived the adjective paganus, referring to anyone or anything belonging to such a village district. By the first century AD, the word as noun had acquired the pejorative connotation of English “yokel,” “hayseed,” or “redneck,” reflecting the urban bias of Imperial Rome. But it was only after the cities had adopted Christianity, while the rural districts had not, that the word acquired the added meaning of “someone who follows the old ways and worships the old Gods.” It was in the villages, farms, and forests that the ethnic identity, ancient customs, and religious practices of old continued, so to call someone a redneck was also to say something about his religion, not unlike today but with an even stronger association.

To look at maps of Christianity’s spread and conclude that even the rural areas of the erstwhile Roman Empire were Christian by 600 AD would be an error, because such dates reflect official conversions, such as that of the Frankish king Clovis in 496. How well that decision was even conceptually understood by the ruler making it is one question, and how well it trickled down to the common people is yet another. In Charlemagne’s day, three centuries later, Franks in the countryside were still reciting the old pagan songs, which his grandson Louis the Pious—unfortunately—uprooted and ended.