For many years music remained a private amusement to which Nietzsche delivered himself up in a spirit of irresponsible pleasure, with the pure delight of an amateur, a pastime altogether outside his main “mission” in life. Music flooded his being only after the philological crust had been removed, only when his erudite objectivity of outlook had become disintegrated, when his cosmos had been shattered as if by a volcanic eruption.

Precisely because he had pent up these primal springs of his nature for so long behind the damns of philology, erudition, and indifference, did they gush forth so vehemently and penetrate into every crevice, irradiating and liquefying his literary style. It was as if his tongue, which had hitherto sought to explain tangible things, had suddenly refused its allotted task and insisted upon expressing itself in terms of music. Even his punctuation—unspoken speech—his dashes, his italics, could find equivalents in the terminology of the elements of music.

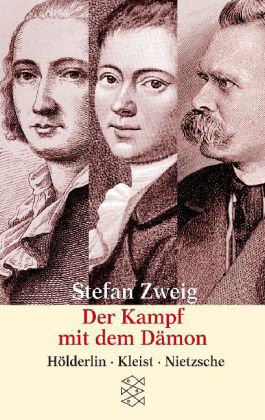

The details of each work are vibrant with music, and the works as a whole read like symphonies. They no longer belong to the realm of architecture, of intellectual and objective creations, but are the direct outcome of musical inspiration. Of Thus Spake Zarathustra he himself says that it was written “in the spirit of the first phrase of the Ninth Symphony.” And how better can I describe the opening of Ecce Homo than as a magnificent organ prelude destined to be played in some vast cathedral? “Song of Night” and “Gondolier’s Chanty” resemble the croonings of primitive men in the midst of an infinite solitude. When was his inspiration more joyous and dancing, more heroic, more like a lilting cadence of the Grecian music of antiquity, than in the pæan indited during his ultimate outburst of happiness, in the Dionysian rhapsody? Illuminated from on high by the pellucid skies of the South, soaked from beneath by the waters of music, his language became as it were a wave, restless and immense.

Music, limpid, freedom-giving, and light, became the dearest solace of Nietzsche’s agitated mind. “Life without music is nothing but fatigue and error.” “Was a man ever so athirst for music as I?” He, the solitary wanderer cast out by the gods desired only that they should not rob him of this one consolation, this nectar, this ambrosia which eternally refreshed and reinvigorated the soul. “Art, nothing but art! Art was given us that we might not be slain by truth.”

The world had forsaken him; his friends had long since gone their ways and ignored his existence; his thoughts strayed forth on interminable pilgrimages. Music alone walked by his side, accompanying him into his final, his seventh, solitude.

When in the end he fell into the abyss, she watched over his obliterated mind. Overbeck, coming into the room after the catastrophe, found the unhappy madman sitting at the piano, his fingers fumbling the keys in a vain effort to find the harmonies so dear to him.

One reply on “Flight into music”

Touching. Music, truly, is the greatest salve and most wonderous fount of joy.

IFA