by Eduardo Velasco

Previous Heartland entries: 1, 2 and 3.

‘The Heartland is the greatest natural fortress on Earth’. —Mackinder.

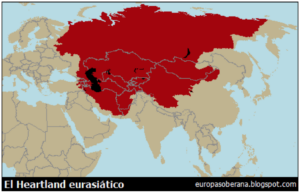

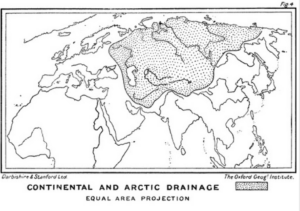

Heartland comes from heart and land, ‘cardinal region’. The Heartland is the sum of a series of contiguous river basins whose waters flow into bodies of water inaccessible to oceanic navigation. It is the endorheic basins of Central Eurasia plus the part of the Arctic Ocean basin frozen in the Northern Route with an ice cover of between 1.2 and 2 metres, and therefore impassable for much of the year—except for atomic-powered icebreakers (which only the Russian Federation possesses) and similar vessels. Although the word was first used in its specific meaning by James Fairgrieve (a Mackinderian disciple) in Geography and World Power (1915), the concept of Heartland was first defined by the English geographer Halford John Mackinder (1861-1947), one of the founding fathers of modern geopolitics, in his work The Geographical Pivot of History (1904), where he drew the first graphic representation of what he initially called the ‘Pivot Area’:

Mackinder says in his more comprehensive Democratic Ideals and Reality (1919):

The northern margin of Asia is an inaccessible coast, clogged with ice except for a narrow waterway which opens here and there along the beach during the summer, owing to the melting of the local ice formed during the winter between the floes and the land. It so happens that three of the world’s largest rivers, the Lena, the Yenisei and the Obi, flow northwards through Siberia to this coast, and are therefore divorced for practical purposes from the general system of ocean and river navigation. South of Siberia are other regions at least as extensive, drained into salt lakes with no oceanic outlet; such are the basins of the Volga and Ural rivers flowing into the Caspian, and of the Oxo[1] and Jaxartes[2] into the Aral Sea. Geographers usually describe these internal basins as ‘continental’. Taken together, the Arctic and continental flow regions occupy almost half of Asia and a quarter of Europe and form a large continuous patch in the north and centre of the continent. This entire patch, stretching from the icy, flat shores of Siberia to the torrid, rugged coasts of Baluchistan and Persia, has been inaccessible to oceanic navigation. Its opening by railways—for it had no roads beforehand—and by air routes shortly, constitutes a revolution in the relations of men with the greatest geographical realities of the world. Let us call this great region the Heartland of the Continent.

Sticking strictly to the Mackinderian definition of the Heartland, its exact extent would be as follows:

Mackinder describes the interior of this Heartland in these terms:

The north, centre, and west of the Heartland are a plain, rising only a few hundred feet at most above sea level. In that greatest lowland on the Globe are included Western Siberia, Turkestan, and the Volga basin of Europe, for the Ural Mountains, though a long range, are not of important height, and terminate some three hundred miles north of the Caspian, leaving a broad gateway from Siberia into Europe. Let us speak of this vast plain as the Great Lowland.

Southward the Great Lowland ends along the foot of a tableland, whose average elevation is about half a mile, with mountain ridges rising to a mile and a half. This tableland bears upon its broad back the three countries of Persia, Afghanistan, and Baluchistan; for convenience we may describe the whole of it as the Iranian Upland. The Heartland, in the sense of the region of Arctic and Continental drainage, includes most of the Great Lowland and most of the Iranian Upland; it extends therefore to the long, high, curving brink of the Persian Mountains, beyond which is the depression occupied by the Euphrates Valley and the Persian Gulf.

The Eurasian steppe is the most traversable and open part of what Mackinder called the Great Lowland. It can be considered the backbone of Eurasia and the cradle of pastoralism, the spirit of chivalry and land power. Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Mongolia are the key countries for its domination, indeed control of the steppe is a strategic imperative for the Russian Federation—in the same way, Atlanticism ensures that the steppe is never under the control of a single superpower. The Dzungaria Gate, marked on the map, is a mountain pass that separates Uyghuristan from the rest of Central Asia. Mastering such a mountainous strait is as important to a tellurocracy as control of a sea strait is to a thalassocracy. Between the Great Western Steppe (from Hungary to Kazakhstan) and the Great Eastern Steppe (mainly Mongolia and Manchuria), there is only one major barrier: the Altai massif. Budapest, Bucharest, Odesa, Kiev, Volgograd (Stalingrad), Astana, Omsk and Ulan Bator are key cities in the structuring of the Eurasian steppe.

The basis of geopolitics is the contradiction between sea power (‘thalassocracy’ in Greek) and land power (telurocracy). Sea power tends to engender commercial and liberal states, and land power productive and autocratic states. Typical historical thalassocracies have been Phoenicia, Athens, Carthage, Venice, the Hanseatic League, the Republic of Ragusa, the Republic of Salé, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Holland, the British Empire and the United States after 1898. Clear telurocracies have been the Scythians, Sparta, the Holy Roman Empire, the Mongol Empire, the Russian Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, the USA before 1898 and the USSR.

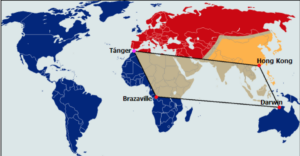

Both types of power have their natural citadels and their spheres of influence in the terrestrial geography. The citadel of thalassocracy is the northern half of the Atlantic (Midland Ocean or Mediterranean Sea) and its sphere of influence is Oceania described in 1984 by George Orwell, who knew geopolitics. The citadel of the telurocracy is the Heartland and its sphere of influence is Orwellian Eurasia. The Eurasia of 1984 would, in reality, be, along with other regions of the globe, contested between the two archetypal powers, or have a mixture of both: Southeast Asia, Korea, South India and the Chinese coast would have strong oceanic influence, while Tibet, Uiguristan, Inner and Outer Mongolia, Manchuria and Northern India would have continental influence. According to Orwell, in a world where geopolitics has taken over, the contested areas of the globe—perpetually at war, changing hands and being conquered and reconquered again and again by the three superpowers—form a quadrangle with corners at Tangier-Hong Kong-Darwin-Brazaville, as well as the borders between Stasia and Eurasia. These disputed territories loosely correspond to the Muslim world.

Above, the natural citadels of the thalassocracy and the telurocracy. It will be noted that the shortest way between the two is Scandinavia and the Arctic Ocean, near the Russian-Norwegian border. Europe in general has the misfortune of being the natural battleground between thalassocracy and telurocracy. At present, a new thalassocratic space is forming in the Asia-Pacific, which, together with the Atlantic from the West, besieges the Heartland from the East.

Above, in George Orwell’s novel 1984, there is a fictional essay entitled The Theory and Practice of Oligarchic Collectivism, which explains how the USSR has conquered Western Europe to become Eurasia (red), the United States and the British Empire have united to form Oceania (blue), and Stasia (yellow) has emerged after a decade of confused struggles. None of the three superstates can be conquered even by the other two combined, as their military might be at the same level and their natural defences are too formidable. Within the Tangier-Hong Kong-Darwin-Brazaville quadrangle lie the contested zones of the planet. The borders between Eurasia and Stasia are not entirely clear, except for a reference to the unstable border in Mongolia.

Globalisation has its throne in ‘markets’ (mainly banks and multinationals) and in international trade, 90% of which is conducted by sea, even though rail and pipelines are cheaper, faster and more efficient—or would be if it were not for timely instabilities in the most strategic links of land routes. A landlocked state thus has a large vector of influence projection at its disposal and shares a de facto border with all countries with a coastline on the body of water in question.

Unlike the emerged lands, the planet’s seas constitute a single body (Panthalasa or World Ocean theory), so that whoever goes out into the World Ocean and dominates it will tend to envelop all the world’s emerged lands and infiltrate its power into them, especially through the valleys and plains of the great river basins. But despite this great advantage, the sea, changeable, capricious and shifting, serves only to transport things that come from the land and to lay siege to the land itself. If dominating the sea is merely a means to dominate the land, dominating the land is an end in itself so that a maritime superpower needs to besiege the land only confirms the importance of the land itself.

Halford J. Mackinder

This article will therefore take the point of view of the sea’s natural antagonist. The land represents the firm, stable, fertile, nourishing, productive, organised and disciplined, if the sea is very similar to the ‘becoming’ with its ups and downs, the land is close to the ‘being’ with its obstinate permanence. If the sea rises only in stormy moments, the land rises forever in the mountains, which could be defined as ‘concentrated land’. In the economic sphere, the telluric strategy is not to move goods from one place to another but to produce them and make them stay as close as possible to the soil from which they sprang.

Productivity and fertility thus replace trade and speculation to form a political, economic and social system very different from the one that prevails on the planet today. Likewise, the opening up of spaces of free navigation, which is the obsession of Atlanticism, is replaced by the tendency of the great land masses to strangle maritime traffic in delicate bottlenecks, to break up Panthalasa, turning the various seas into mere inland lakes under tight control. For, as we shall see in another article, the Baltic, the Black Sea, the Adriatic, the Aegean, the entire Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Andaman Sea, the South China Sea, the Sea of Japan, and even the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and Hudson Bay, can be excised from the bosom of the World Ocean and turned into lakes as inaccessible as the Caspian, just by activating natural locks: sea straits like Gibraltar or Hormuz, or island barriers like Japan or the Andaman Arc.

_____________

[1] Oxo or Oxus was the Greek name for the Amur Darya (Pamir) river.

[2] The Greek name for the Syr Darya.