“Ma, we got milk a-plenty. Cain’t I git me a leetle ol’ fawn for a pet for me? A spotted fawn, Ma. Cain’t I?”

This was exactly the sort of dialogue that, as an adult, I expected to read in a novel I had only known from its illustrations. But this—:

Jody picked up his gun and started away. He would give anything to bring down a buck alone.

The buck lay in the shade of the live oak. Penny had already begun the dressing.

—I would have never, ever imagined as the child I was.

He said, “I wisht we could git our meat without killin’ it.”

“Hit’s a pity, a’right. But we got to eat.”

Penny was working deftly. His hunting knife, a flat saw-file ground down to an edge, with only a corn-cob for handle, was not overly sharp, but he had already drawn the venison and cut off the heavy head. He skinned it below the knees, crossed the legs and tied them, slipped his arms through the junctures, and stood up with the carcass neatly balanced on his back for carrying.

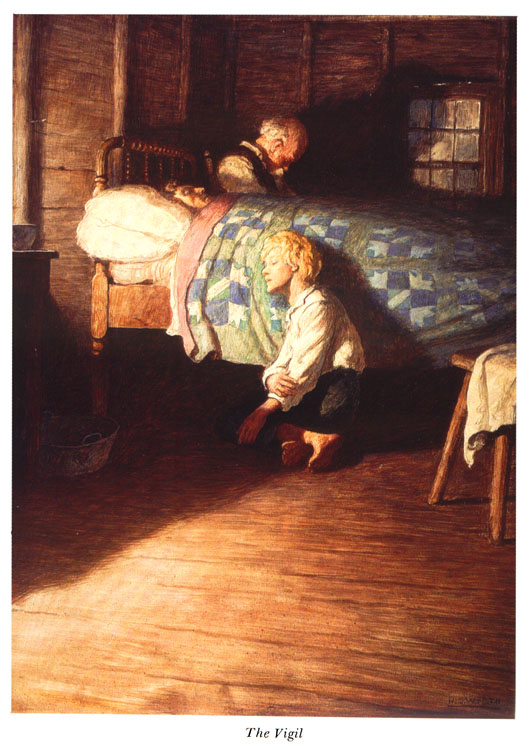

As I child I naively thought that all of the contents of the novel would be as bucolic as Wyeth’s illustrations. Those idyllic child memories explain the surprise I felt as the adult who, decades later, actually read the novel’s contents including lots of skinning of dead animals.

The chapter that introduces Grandma Hutto contains a passage that throws light onto the character of Jody’s mother:

Penny went to the rear of the cottage with the venison and the hide. They were all welcome here, father and son and battle-scarred hound. Jody felt more at home than when he returned to his own mother.

He said, “I reckon you wouldn’t be so proud to see me, did you have to put up with me all the time.”

Grandma chuckled.

“You’ve heard your Ma say that. Did she quarrel about you comin?”

“Not so turrible as sometimes.”

“Your father,” she said tartly, “married a woman all Hell couldn’t amuse.”

Despite the numerous hunting and skinning of animal bodies, Jody was a compassionate kid.

He recalled a wild-cat that the dogs had torn to pieces. Wild-cats deserved what they got. Yet at one moment, when the snarling mouth had gaped wide in agony, and the evil eyes had filmed in dying, he had been stabbed with pity.

Later the Forresters stole from the Baxters some pigs which Penny wanted back. With Jody he was on route to the Forrester’s place trying to pick a fight but was bitten by a rattlesnake. Addressing his son—:

He said quietly, “I cain’t do it no more good. I’m goin’ on home. You go to the Forresters and git ’em to ride to the Branch for Doc Wilson.”

“Reckon they’ll go?”

“We got to chance it. Call out to ’em quick, sayin’, afore they chunk somethin’ at you or mebbe shoot.”

A hunted doe’s liver and heart were used to absorb the snake’s venom.

He turned back to pick up the beaten trail. Jody followed. Over his shoulder he heard a light rustling. He looked back. A spotted fawn stood peering from the edge of the clearing, wavering on uncertain legs. Its dark eyes were wide and wondering.

He called out, “Pa! The doe’s got a fawn.”

“Sorry, boy. I cain’t he’p it. Come on.”

An agony for the fawn came over him. He hesitated. It tossed its small head, bewildered. It wobbled to the carcass of the doe and leaned to smell it. It bleated.

Penny called, “Git a move on, young un.”

On route to the Forresters’ home Jody—:

had never minded night or darkness, but Penny had always been in front of him.

Dr Wilson spent the night with the Baxters trying to save Penny’s life. Jody was worried of both, his father and the little orphan:

He remembered the fawn. He sat upright.

The fawn was alone in the night, as he had been alone. The catastrophe that might take his father had made it motherless.

The fawn was alone in the night, as he had been alone. The catastrophe that might take his father had made it motherless.

It had lain hungry and bewildered through the thunder and rain and lightning, close to the devastated body of its dam, waiting for the stiff form to arise and give it warmth and food and comfort. He pressed his face into the hanging covers of the bed and cried bitterly. He was torn with hate for all death and pity for all aloneness.