by Eduardo Velasco

Antiquity

The first great empire of the Heartland, the Persians, arose after the irruption onto the Iranian plateau of various Aryan tribes from present-day Russia and Ukraine: the Medes, Persians and Parthians. Since then, Persia has been a country that has merely recycled itself as an empire over and over again throughout history, tending to project power across the five seas of Penthalasia (Mediterranean, Black Sea, Caspian, Persian Gulf and Red Sea) and to be a bridge between Europe-Esthasia, Stasia-Africa, Central Asia-Indian and the Eurasian and Arabian Heartland.

The 4th century saw an event that would have a decisive influence on the consolidation of the Silk Road as the backbone of international trade: the eastward thrust of Alexander the Great. Starting from their Balkan base in northern Greece, the Macedonians conquered Anatolia, the Levant, Pentalasia, Egypt and the Achaemenid Empire, reaching as far as India. The Greeks founded several Alexandrias in the Heartland: Alexandria of Aria (today’s Afghan city of Herat, through which passes a strategic gas pipeline and road, and near which there is a Spanish-Italian military base), Alexandria Eschate (today’s Jodzend, Tajikistan), Alexandria of Oxo (today’s Ai Khanum, Afghanistan), Alexandria Caucasus (probably present-day Bagram, Afghanistan, where there is a major NATO air base) and Alexandria Aracosia (present-day Kandahar, Afghanistan, where there is another US military base). According to Isidore of Carax, the Parthians called this region ‘White India’. North of these militarised and fortified Greek colonies, the Scythians and Masagetes—whom Alexander the Great never dared to attack—flowed freely across the steppe. The Macedonians had reached the gates of Gog and Magog.

Citadel of Herat (Afghanistan), the ancient capital of a Persian province described by Herodotus as ‘the granary of Central Asia’. Given the success of Macedonian conquests in the Greater East, it is understandable that Pompey, Trajan, the medieval Crusaders, Napoleon, today’s NATO armies and any Western power seeking to penetrate deep into Asia would look to Alexander the Great.

Greek expeditions from the Tajik valley of Fergana reached the city of Kashgar (present-day Uiguristan), home to an Indo-European tribe, the Tocaryans. The Dayuan (‘great Ionians’) of the Han Chinese chronicles are believed to be descendants of these Greek settlers of the Heartland. Alexander the Great was the first who, by stabilising a vast space between the Great West and the Great East, opened both domains to mutual trade. Thus, the most important and lasting effect of the Macedonian campaigns was the definitive opening of the Silk Road.

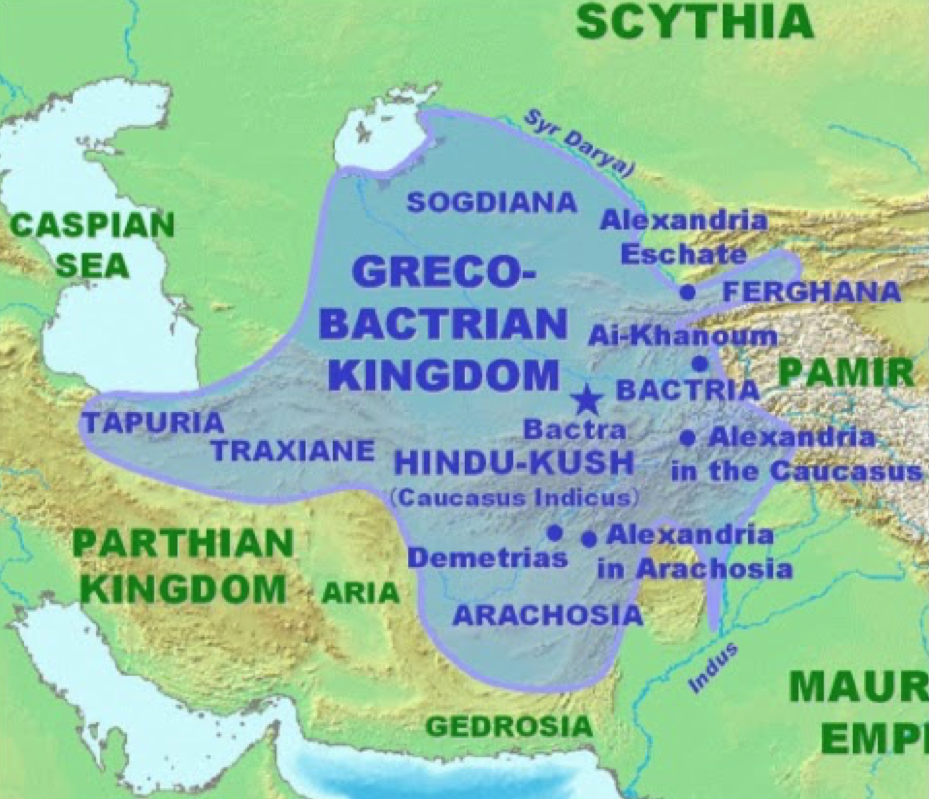

When Alexander the Great died in 323 b.c.e., the Diadoks (generals of the Macedonian army) divided up his empire, fighting for twenty years for regional hegemony. After his death, the epigones, his successors, reigned over the territorial units resulting from the fragmentation of the Alexandrian empire. The one that interests us most in this article is the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, centred in Bactria (present-day Balkh, northern Afghanistan). The 3rd century b.c.e. saw the entry into this Greek domain of Buddhism from the Maurya Empire of India, with which the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom maintained numerous political and commercial relations. It is the beginning of an extraordinary Hellenistic-Buddhist civilisation, led by Greek monks and a Greek military aristocracy, descendants of the ancient Macedonian armies, in the heart of Central Asia, an episode rarely remembered in modern historiography.[1]

Approximate extent of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom in 180 b.c.e. By this time, Buddhism with pagan-Hellenic influences was already the dominant religion, to the extent that reliefs of the Hindu Buddha protected by the Greek Herakles were sculpted. Despite the problematic mountain barriers, the kingdom was mainly oriented towards India. It dominated an important segment of the Silk Road, controlling the exits from China to the West.

The earliest artistic depictions of the Buddha, which strongly influenced Buddhist imagery throughout Asia, occurred in this kingdom. It has even been reasonably speculated that Apollo influenced the early sculptures of the Hindu saint so that the legacy of the more typically Western god would have reached the Pacific—something the shepherd warriors of the Balkans could surely never have imagined. The entire Gandhara artistic current is of Greek and therefore European genesis. In the middle of the Silk Road, the colossal Buddha statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan, demolished by the Taliban in March 2001), were clearly of Greco-Buddhist heritage. This cultural stream is a superb example of the extraordinary fruits that a healthy and positive interaction between the West and the East could bring.

Museum, Lahore, Pakistan. This 2nd-century Gandhara statue is the Greek Athena, sculpted in the Greek style and with facial features typical of the aristocracy of classical Greece. It is part of the legacy of the first European state in the Heartland.

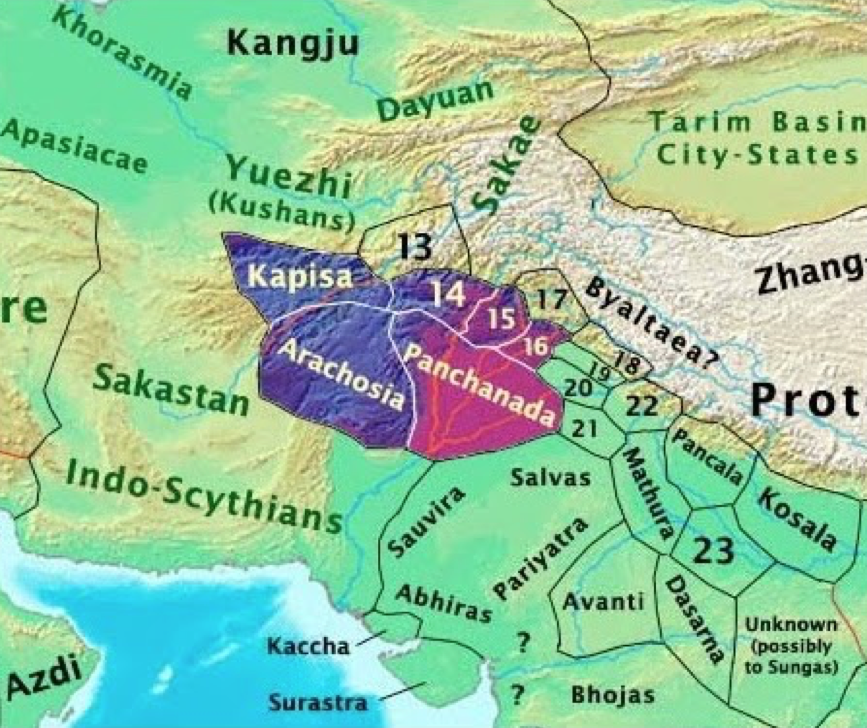

Around 130 b.c.e., the Greco-Bactrian kingdom was overrun by the Toccharians, who eventually founded the Kushan Empire. For a time, however, the Indo-Greek kingdom survived, detached from the Greco-Bactrian when the latter conquered the Indus basin and part of the Ganges basin in an expansion reminiscent of the Indo-Aryan conquests fourteen centuries earlier.

Indo-Greek kingdoms in 100 b.c.e., in what are now Afghanistan and Pakistan. 14: Pushkalavati. 15: Taxila. 16: Sakala. They occupy a position straddling the Heartland and the fertile, overpopulated, rich plains of the Indus and Ganges. They include what are now the AFPAK frontier and the troubled tribal areas of Pakistan. These kingdoms, following in the footsteps of the ancient Indo-Aryans, will eventually conquer much of the Indus and Ganges basins. It will be noted that the regions of Nuristan (Afghanistan) and the Chitral and Hunza valleys (Pakistan), where European physical features have been best preserved to this day, fall within this area of Hellenistic influence.

The Macedonian push into the heart of Asia was merely the logical climax of the process initiated centuries earlier by the Greek colonies in Asia Minor, now western Turkey. By now it will have been appreciated that in Hindu civilisation, centred in North Hindustan, the influence of the Heartland predominates, even though India was later conquered by a typically maritime empire such as the British.[2] It seems that since then, the mountainous territories separating Hindustan from Central Asia have been a clear battlefront between thalassocracy and telurocracy. Inevitably, this reminds us of the role of Afghanistan and Pakistan on the international scene today.

Both Rome and China were mutually aware of the existence of the other empire and maintained to some extent essentially indirect relations. The Han Empire regarded Rome as a kind of Western counterpart, and Rome probably had the same image as China. However, between the two powers stood two states in the former Alexandrian conquests: the Parthian Empire and the Kushan Empire. Rome tended to push eastwards, eventually conquering the Caucasus and what is now Iraq, but problems in the Levant meant that Roman conquests in the rest of Pentalasia were rather short-lived. The Mediterranean was the only sea that Rome could call Mare Nostrum; neither the North Sea, the Atlantic, nor the Black Sea, nor the Red Sea—let alone the Caspian or the Persian Gulf—could be called fully Roman.

The Roman Senate even proclaimed several edicts prohibiting, in vain, the use of silk, since its trade bled the Empire of its gold reserves, which indicates that two millennia ago, what happened at one end of the Silk Road influenced the opposite end—an example of proto-globalisation. Pliny the Elder said in Natural History that ‘by the lowest estimate, India, Seres and Arabia cause our Empire to lose 100 million sesterces every year: this is what our luxuries and our women cost us’. There seems to have been phenomena in Rome comparable to the flow of silver to China before the opium wars, as well as the loosening of patriarchy in the West today.

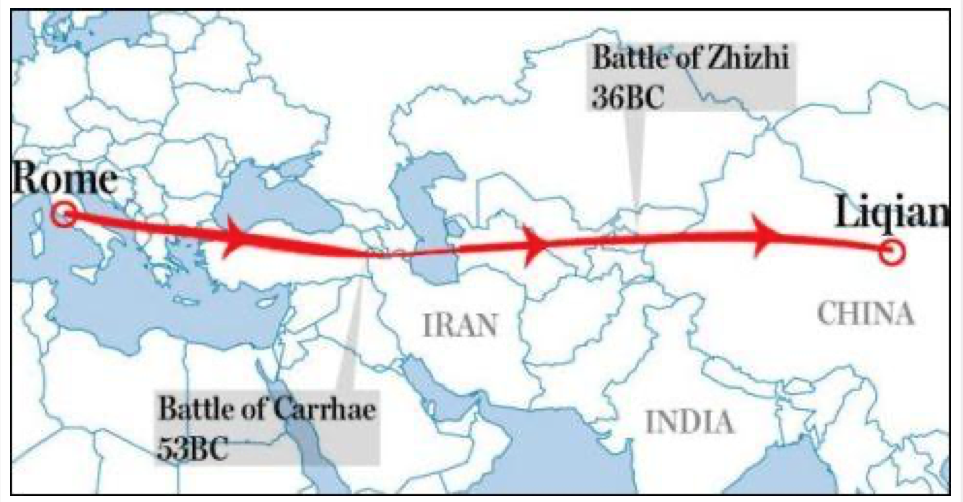

In 56 b.c.e., Rome fights the Parthian Empire at the battle of Carras (modern-day Kurdistan). The feared Parthian cavalry manages to defeat the legion and Crassus, the Roman general, is executed. Ten thousand Roman soldiers were taken prisoner and deported to the far east of the enemy empire, to the Eurasian Heartland; specifically to Bactriana (Afghanistan). Plutarch and Pliny the Elder tell us that many of the Roman survivors were enslaved or sent to forced labour, but that some managed to make their way into the world of labour as mercenaries. These Roman troops were supposedly used by the Parthians to fight the Huns in the province of Margiana, which is now Turkmenistan. The Roman Empire and the Parthians signed a peace treaty in 20 b.c.e. and attempts were made to bring back the prisoners, but by then all traces of the ill-fated legion had been lost. Han chronicles from 36 b.c.e., describing a Chinese military campaign in western China, tell of a disciplined enemy army guarding the square of Zhizhi, present-day Uzbekistan. These chronicles mention a quadrangular wooden fortress and enemy soldiers entering the battle perfectly aligned and building a fish-scale-like formation with their shields: the ‘tortoise’ of the Roman legions had arrived in the Heartland. After finally being defeated, these soldiers were taken, again as mercenaries, to the southern frontier of the Gobi Desert, to protect China from barbarian raids. They were eventually settled at Li-Jien (present-day Liqian), a node on the Silk Road whose very name is a corruption of ‘legion’. The presence of the ‘lost legion of Crassus’ was brought up in 2001 and genetic analysis has confirmed the trace of European blood in this area, a presence that can be seen with the naked eye in the high frequency of more aquiline noses, wavy brown hair and light eyes.

The journey of the ‘lost legion’.

The incursion of the Roman legions into the Levant catalysed a historical process of enormous importance. In the 1st and 2nd centuries, several ethnic cleansings of Greeks took place in the Eastern Mediterranean. Cyprus, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Crete, Crete, Sicily, Rhodes and elsewhere saw Jewish communities, taking advantage of the absence of Roman legions engaged in a military campaign against the Parthian Empire, rise in complete synchronicity against the hated Greek communities of the region. Although these Jewish revolts would be harshly put down by Rome, the Europeanisation of the Levant would never come to fruition, Jewish collaboration with the Parthian Empire would continue and, in the long run, the entire Roman Empire would be semi-ethnicised and would see the eradication of the Greco-Latin legacy, this time under a Christian sign, in a much more resounding way. These ethnic cleansings of European populations were a reaction to the will of the deserted, dry and infertile East, the effect of which was to break the continuity of Greek culture from the Roman Empire to India. The Greek pockets in India and Central Asia, deprived of the source of their culture and human capital, would gradually lose influence until they were swallowed up by the Heartland. It would be fourteen centuries before another power, this time Russia, would reintroduce the flame of Greek culture into the heart of the continent.

The Huns, who emerged from the Heartland in the latter days of the Roman Empire, are of nebulous ethnogenesis. We know that they were a society of pastoral warriors whose main foodstuffs were meat and milk, and whose military tactics were based on large formations of light cavalry masterfully employing the bow and javelin throw. The Huns were, rather than a specific ethnic group, a confederation of steppe horsemen, whose ranks included Ural-Uralic, Turkic, Mongol, Iranian, Germanic, Slavic and other peoples, probably dominated by a Turkic-Mongol aristocracy, although in the Hunnic territories of Eastern Europe, the lingua franca was Gothic. At Attila’s death, his confederation dissolved as quickly as it had appeared, but the effects of its brief existence—notably setting in motion the great migration of the Germanic peoples who were to constitute the medieval nobilities of Western Europe—were to endure for a long time.

The case of the Huns is comparable to that of the silk trade in terms of the repercussions at one end of the Silk Road of what happened at the other end, for if the Huns spilt over into Europe, it was because they could not spill over into China. Europe, unlike Stasia, lacked a state with a clear strategic doctrine that took into account the importance of the Heartland. On the contrary, the Chinese, who had already built dams to control the disastrous floods of the Yellow River (whose sources are in the Heartland), had decided to dam the human floods coming from the heart of the continent by building the Great Wall of China—again, to preserve their ‘political order’. The Great Wall is an impressive testimony to the importance of the Eurasian hinterland; in many sections, it coincides exactly with the boundaries of the Heartland. It seems that the Chinese emperors saw the Heartland as an impenetrable domain, a source of barbarians and a hornet’s nest best left alone. But the Great Wall was not merely a military barrier, it was also a transport corridor and a system of locks to extract taxes, fees and tolls from Silk Road trade, levy tariffs and control migratory flows.

The fact that the Great Wall is more like an infrastructure of countless different walls, built over eighteen centuries, shows that defending against the Heartland tribes was a constant obsession for successive Chinese dynasties. The Mongols had a diet based on animal products and were, as a people, more warlike than the Chinese, although China had the most effective martial traditions in the world.

In 431, Nestorian Christianity was condemned by the First Council of Ephesus, leading to a great exile of Nestorian Christians to Sassanid Persia. Henceforth, Baghdad and Seleukia-Ctesiphon were centres of Nestorianism, which sent large numbers of missionaries (or perhaps better said ‘agents’, mainly Syrians and Persians) to the far reaches of the continent, founding Christian communities throughout most of Asia. Cities such as Herat, Farah, Almalik (known to 14th-century Christians as Armalec), Samarkand, Kashgar and even Tang-era Beijing itself, were home to thriving Nestorian communities from the early Middle Ages onwards.

___________

[2] Conquerors of India from the Heartland include the Indo-Aryans, the Macedonians and the Mongols (Moghul dynasty, still active in the 18th century). Nor can the Persian influence be underestimated: Persian was in many parts of India the cultured language of the social elite until the arrival of the English.

One reply on “Heartland, 6”

Although technically true, something Velasco and I disagree on is that he had Sparta as the Aryan paradigm and I have Hitler’s Germany as our paradigm. From this angle the one-drop rule applies; that is, exterminationism as devised by Himmler and his people.

It is a pity that due to the type of illness that David Irving suffered early this year (stroke?) he was unable to complete the second volume of his biography of Himmler. But I assume, from what he has said in previous lectures, that he apparently accepts the Master Plan East as historically authentic.

In short, Velasco was not an exterminationist like me. Just look at how the current populations of the above-discussed geographic regions appear after centuries of interbreeding!

And here I see that I disagree with virtually all of the racial right except Andrew Anglin. From the corruption of women comes all misfortune, says the Sanskrit motto. It seems obvious to me that we must revalue values back to the times when Roman women could not possess savings. At the time Velasco refers to, imperial Rome considerably had relaxed patriarchy to the point that what is mentioned above occurred.