by Eduardo Velasco

Endorheic basins and the importance of river systems

The word endorheic comes from the Greek ἔνδον (éndon, internal) and ῥεῖν (rheîn, to flow). The second word shares a root with the Rhine and Rhea, a chthonic primordial goddess in Greek mythology. An endorheic river basin is thus an internal flow basin or, if you prefer, a closed-loop basin, where waters don’t spill into the seas, but remain enclosed until they flow into terminal central ‘navels’, especially lakes (often saline, such as the Caspian, the Dead Sea or Great Salt Lake), cave systems, underground streams, aquifers, oases, swamps, quicksands and other enclosed spaces. Unlike other river basins, which are open to an ocean and therefore imperfect, endorheic basins are perfect water-holding basins, closed caverns where water currents flowing over the surface can neither enter nor leave.

If the world within conventional sea basins represents the waste, change and explosion of the perishable (‘our lives are the rivers that flow into the sea, which is death’, wrote Jorge Manrique in the 15th century), within endorheic continental basins it represents the conservation, fermentation, cultivation and implosion of the perennial. Indeed, civilisation itself, whose essence is becoming and dilapidation, was born in sea basins: that of the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf—although interestingly, Jericho, the first city in the archaeological record with walls, towers and fortifications, arose in a small endorheic basin: that of the Dead Sea.

Endorheic basins usually correspond to dry climatologies, since in areas of frequent rainfall, these basins overflow through their lowest outlet, connecting to a conventional basin, or eroding the barrier of least resistance until they find a hydrological outlet (as happened with the Black Sea, formerly a lake, after the last ice age). In dry climates, water evaporates or is absorbed by the subsoil before this can happen. For this reason, humid Europe has hardly any endorheic basins (although the Caspian accounts for 19 per cent of European territory), and these are generally tiny exceptions such as the Akrotiri salt lake in Cyprus, where the UK maintains a Gibraltar-like strategic enclave. In Spain, endorheic systems are small, such as Los Monegros (Aragon) or the Puerto Real Endorheic Complex (Cadiz).

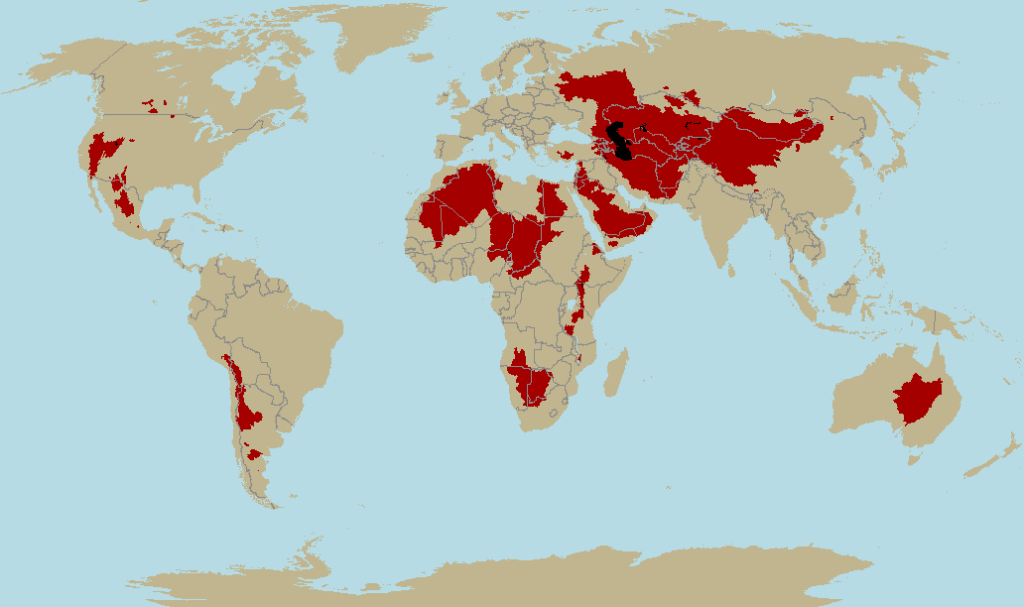

Endorheic basins of the planet.

In geostrategy, river basins aren’t a random or capricious criterion, since they show better than any other force of gravity, that is, the influence of the Earth when driving power. The reason why we will pay so much attention to river basins in this article is that Nature and the will of the Earth always win out in the end—and river basins are an expression of these forces, as their waters descend in obedience to the gravitational pull of the simplest and most logical route.

In Chinese writing, political order is expressed by the ideograms ‘river’ (water element) and ‘dam’ (earth element). The river represents the ‘chaotic’ forces of Nature, which try to be controlled and contained by human civilisation, by ‘order’. As echoed in modern geopolitics many millennia later, rivers are supranational political systems: not for nothing do river basins cross borders, channel goods, influences, technology, armies, religions, ideologies, animals, economies and strategies, as well as provide fertile, wetland on which to grow grain. It was on the banks of the Jordan River that the first proto-civilised societies were born, the Tigris and especially the Euphrates formed the backbone of Mesopotamian civilisations and the Nile was and is the backbone of Egypt, as the Wei River and later the Yellow River basin was at the birth of China. In front of the river, constructing a dam is nothing more than an attempt to create an artificial endorheic basin.

River basins are also natural infiltration routes from the sea: the Neolithic entered Europe via the Danube, as the Ottomans will do millennia later—the First Crusade will take the same route in reverse.

The Romans entered Hispania via the Ebro and the Moors via the Guadalquivir, and from the tributaries of these rivers, they branched out their strategy of conquest and domination.

The simple fact of going up rivers (Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio and St. Lawrence) gave the French control over an area of North America far greater than that controlled by the English, while the Belgians were able to dominate what is now Congo-Kinshasa thanks to the Congo River and its tributaries.

Even the Vikings had the great, easily navigable rivers of the East to thank for their domination of the Russias or their arrival in the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate of Baghdad. Thanks to the rivers of Western Europe, the Vikings were able to reach such important cities as Paris, Seville and Pamplona.

The Pearl River was the gateway for British influence in China, and the Yangtze for Japanese influence. Further south, the Mekong was crucial to incorporate Indochina into the French Empire.

In South Africa, the Orange, Vaal and Limpopo rivers were key to Boer expansion. The Zambezi basin gave its name to Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company’s geopolitical project in the African interior, which was called Zambesia before being renamed Rhodesia.

The conflicts in Rwanda were also about a river basin struggle (Nile vs. Congo), as in Darfur (Nile vs. endorheic basin of Lake Chad) and today in northern Nigeria (Niger vs. Lake Chad).

Nor is it necessary to recall the extent to which the fertile basin of the Duero provided the backbone of Castile at the time of the Reconquest, the central role of the Ebro in the Spanish Civil War, the role of the Vistula (whose internationalisation was even proposed) and its mouth, the free city of Danzig, in triggering the Second World War, or the importance of the Amazon and the Rio de la Plata for several South American states.

As for North America, the river system of the Mississippi basin plus the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway provides more kilometres of navigable waterways than the rest of the world combined, as well as feeding and surrounding the largest continuous stretch of arable land on the planet, making it a de facto island.

In early 2014, the conflicts in Crimea and Ukraine turned our eyes back to the river basin map, revealing the huge silhouette drawn by the Don River basin, which easily geo-blocks into the Kerch Strait, separating Crimea from Russia. The most pro-Russian part of Ukraine coincides suspiciously with the Ukrainian region of the Don basin. Almost confirming this, the Don Basin People’s Militia (Donbass), a pro-Russian paramilitary group, was formed in these areas.

Shanghai, Hong Kong, Macao, Alexandria, Antwerp, Rotterdam, London, Gdansk, New Orleans, New York, Buenos Aires, Dhaka, Calcutta, Cairo and Ho Chi Minh City all have in common that they owe their importance to dominating places where a large basin meets the sea. Nor can the development and history of inland cities such as Moscow, Kiev, Volgograd, Frankfurt, Strasbourg, Basel, Paris, Milan, Rome, Budapest, Belgrade, Montreal, Asunción or Chongqing—or in Spain Valladolid, Zaragoza, Toledo, Madrid, Seville or Córdoba—be understood as part of the rivers over which they preside: yet another reason not to underestimate the importance of river systems.

For all these reasons, in States worthy of the name, what happens in their river basins, especially when they are shared with other countries (as in the case of Egypt-Sudan-South Sudan-South Sudan-Uganda-Ethiopia, Bangladesh-India, Burma-China, Vietnam-Cambodia-Laos-Thailand-China, Spain-Portugal, Holland-Germany, Ukraine-Russia or Brazil-Paraguay-Argentina-Uruguay), is a matter of national security.

To give examples, Serbia was stripped of its Mediterranean outlets after it conflicted with NATO, but they could not take away the Danube (a navigable river and therefore a river connection that broke the isolation to which NATO wanted to subject Belgrade), and if Ethiopia and/or Uganda were to do something ‘weird’ at the source of the Nile, they would strangle a nation of 80 million souls in a tremendously effective way.

The same can be said of Turkey, which can take 90% of the waters of the Euphrates from Iraq by diverting it. Syria was also in a position to pressure Israel over the Jordan Springs issue—until Israel invaded and occupied (to this day) the Golan Heights.

Pakistan, too, has tensions with India over the fact that India controls an upper reaches of the Indus River, on which Pakistan’s irrigation systems depend, although its sources are in Tibet.

Perhaps the clearest example is Bangladesh, an unviable state with an ultra-dense and explosive demography (150 million inhabitants, more than Russia, concentrated in a territory the size of Nepal, ultra-flat and low-lying, very sensitive to flooding and rising sea levels), which is completely dependent on the Ganges River, which in turn is controlled by India. As we saw in the article on the Libyan war, the struggle over aquifers and water sources is an irresistible geopolitical reality and will become increasingly so as humanity driven mad by economic and techno-industrial growth pollutes and squanders the planet’s freshwater reserves.

Between basins, there are always natural boundaries such as mountain ranges, or at least a clear watershed, so river basins delimit natural geographic domains. Thus, at the time of the Spanish Empire, the Crown of Castile corresponded essentially to the Atlantic basin of the Iberian Peninsula, while the Crown of Aragon corresponded to the Mediterranean basin: both entities had a geographical coherence that tended to give them political coherence.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire also suspiciously coincided with the Danube basin and the English Thirteen Colonies in North America with the Atlantic basin of the continent; one of the reasons England went to war with its colonies was because it forbade the colonists from crossing the Appalachians (the Proclamation Line), which would have made them break into the huge Mississippi basin, making them a continental entity that would more easily escape the heavily maritime power of London. In those cases where rivers lack this central role, they have a peripheral role as a border between states (the Rio Grande, the Congo, the Orange or the Amur), so their importance remains unquestionable.

When you stand in a conventional sea basin, following the force of gravity and the ‘easiest route’, the land invariably leads you to the sea, which is why it happens so often in history that when a country increases its political and economic power, producing a surplus of material power, it ends up going to sea. But there are other basins where the land leads… to the land. The peculiarity of endorheic basins is that if you are outside the basin, the land will never naturally lead you into it, and if you are inside, the land will never naturally lead you out; in this simple fact, there is an almost metaphysical significance: Heartland is, to all intents and purposes, a bubble, an anomaly, a contradiction in the general geographical system, which is governed by totally different and even opposite laws to those of the rest of the planet’s land surfaces.

Finally, in endorheic basins, the water dams the key to the ‘political order’ are already set by geography.

One reply on “Heartland, 3”

As long-time visitors to The West’s Darkest Hour know, Velasco is the author of our site’s master essay: ‘Rome against Judea; Judea against Rome’, a title based on a phrase by Nietzsche.

Those who wish to read installments 1 and 2 of this long article on the Heartland can click ‘Evropa Soberana (webzine)’ in red letters at the top.

Remember also that the System deplatformed Velasco’s webzine although I rescued his articles in Spanish here.