against the Cross, 18

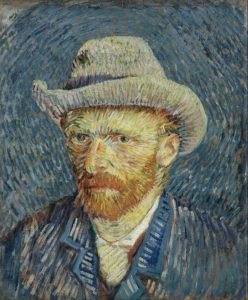

Nietzsche had very little time left with a lucid mind, something he was well aware of, as we saw from Paul Deussen’s testimony about his visit to Sils-Maria. Therefore, working frantically in Turin in 1888, Nietzsche left no less than six works ready for printing: The Case of Wagner, Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Ecce homo, Dithyrambs to Dionysus and Nietzsche contra Wagner! The frenzy of his writing, which as I said reminds me of Van Gogh’s frenzy those very same months under the splendid sun of Arles—which brought out the colours like few other places in the French countryside!—brings to mind Stefan Zweig’s metaphor: the daimon wanted to get out of those bodies using maximum artistic works before they were both burnt by their inner fires (one committed suicide, the other ended up mad).

When the frenzy of writing about everything he had in mind began, Nietzsche was forty-three years old, and in his letters, he admits that his new invective against Wagner was only ‘a distraction’, and that the main work was The Will to Power. But before his magnum opus, now that the muse was visiting him every day without mercy or respite, he wanted to publish a ‘compendium’ of his philosophy: so he rips up the material accumulated for his projected capital work, tears out pages here and there, and shortly sends the compendium to the publisher.

It is essential to know the letters Nietzsche wrote at that time to find out exactly what was going on in his frenetic mind. On 12 September 1888, he told Peter Gast about the compendium: ‘The writing can serve as a kind of initiation, as an appetizer for my Transvaluation of Values’. By this time Nietzsche had already changed the title of his main work, The Will to Power, to Transvaluation of Values. To George Brandes, his discoverer in Copenhagen, he wrote the next day; and to Deussen, the day after that:

Dear friend…

There is already in the hands of my publisher another manuscript, containing a very rigorous and subtle expression of all my philosophical heterodoxy—hidden under much grace and malignity. It is called: A Psychologist’s Idleness. —Ultimately, these two writings [i.e., The Case of Wagner and A Psychologist’s Idleness] are but mere recreations amid an inordinately grave and decisive task, which, if understood, will split the history of mankind into two halves. The meaning of it is stated in five words: Transvaluation of all values.

Around this time he also writes to his old and very understanding friend, the theologian Overbeck:

Dear friend…

To my surprise, the first book of The Transvaluation of All Values is now ready, in its final form, up to the middle. Its energy and transparency are such that perhaps no philosopher has ever achieved them before. It seems to me as if I had suddenly learned to write.

As far as the content or the passion of the problem is concerned, this work splits the millennia—the first book is called, let it be clear between us, The Antichrist, and I would swear that all that has hitherto been thought and said to criticise Christianity is futile childishness in comparison with it. —Such an enterprise makes necessary, even from a hygienic point of view, deep pauses and distractions. One of them will reach you in about ten days: it is called The Case of Wagner: A Musician’s Problem. It’s an all-out declaration of war…

Also, a second manuscript, completely ready for printing, is already in the hands of Mr G.G. Naumann. However, we shall wait a little longer. It is entitled A Psychologist’s Idleness and is very dear to me because it expresses my essential philosophical heterodoxy in a very brief (perhaps also witty) way. Otherwise, it is very ‘tempting’: I say my ‘finesses’ about countless thinkers and artists of today.

Next post I will give some amusing examples of the latter.

Peter Gast’s letter to Nietzsche contained a sentence that led to the title being changed from A Psychologist’s Idleness to Twilight of the Idols. Gast wrote: ‘Ah, I beg you if it is unlawful for an unfit man to beg: a more brilliant, more splendid title!’ Nietzsche replied on 27 September:

Dear friend…

As far as the title was concerned, my own reservations had anticipated your very human objection: I finally found in the words of the prologue the formula which will perhaps also satisfy the need felt by you.

What you write about ‘heavy artillery’ I simply have to accept, being as I am about to finish the first book of the Transvaluation. It really ends with horrible detonations: I don’t think that in all literature you will find anything parallel to this first book as far as orchestral sonority (including cannon fire) is concerned. —The new title (which brings with it very minor modifications in three or four passages) will be:

Twilight of the Idols

or

How to Philosophise with the Hammer

by

F.N.

Proofreading was completed at the beginning of November, and on the 25th of the same month, Nietzsche received the first copies of the work. It would be the last of his writings to reach his hands while he was still lucid (Twilight of the Idols would go on sale at the beginning of the following year).

One reply on “Crusade”

In Arles van Gogh became a painting machine: a triumphant outburst of hidden energies finally went off! His cloths contained streams of sun. Vincent painted tirelessly, even though he knew that no one would buy his oil canvas.